Last year, Cara Marshall’s second-grade son began coming home from school cranky and upset. After five days, she discovered why. His teacher at their neighborhood school in Colorado Springs had taken recess away from the whole class for the week as a punishment for group misbehavior.

After Marshall and a couple other parents approached the principal, the whole-class discipline stopped, but Marshall’s son and a few other boys continued to lose recess for individual infractions for another five days. Instead of going outside to the playground, the boys waited with a teacher in the classroom until recess was over.

“At the time, I didn’t realize it was as wrong as it is,” she said.

Marshall is not alone in believing recess shouldn’t be taken away. In fact, some school districts have wellness policies that prohibit the punishment. Still, it’s a time-honored practice at many schools in Colorado and across the country.

In some cases, teachers take away recess when students misbehave, fail to turn in homework or are late for school. In others, students must complete unfinished classwork during recess before they go to the playground. Proponents say the practice of taking away recess has been around as long as school itself and that teachers have limited options when it comes to discipline. They also say it works.

Examining the consequences

Opponents of withholding recess say it’s counterproductive, both in light of research linking physical activity and academic performance and the problem of childhood obesity. They also say that losing recess can make children with behavior problems harder to handle not easier.

In Marshall’s case, her frustration over the punishment with both her second-grade son, and later her fourth-grade son, factored into her decision to switch her children, including her younger daughter, to a charter school this year.

“It’s been an ingrained policy in a lot of schools,” said Ray Browning, assistant professor in the Department of Health and Exercise Science at Colorado State University. “Teachers are pressured. I totally get it.”

Still, he said children get a substantial part of the federally-recommended 60 minutes of daily physical activity from school recess and “if you withhold one of those recess periods you undermine that child’s chance to be physically active.”

Browning, the father of a fifth-grader and kindergartener who attend Bennett Elementary in the Poudre School District, said he has approached his children’s teachers every year to ask that recess is never withheld as a punishment. Although there was one particularly difficult conversation, the teachers have all agreed.

“I do think we owe it to our kids to be proactive,” he said. “There are very good reasons why children will perform better if they are given the opportunity to move.”

Research shows that physical activity positively impacts cognitive skills, focus and on-task classroom behavior. In addition, students who are physically fit have been shown to have fewer discipline problems, stronger academic performance and better school attendance. A recent study published in the Journal of Pediatrics found that aerobically-fit students did better on math and reading tests than aerobically-unfit students.

While the amount of scheduled recess varies widely by school, younger elementary students often get 20-40 minutes a day, divided into two or three segments. Older elementary students often get 15-20 minutes a day in one or two segments.

A natural consequence

Aurora teacher Cristen Recker is one educator who believes taking away recess has a place in the teacher tool box. Students in her first-grade classroom who do not complete their class work must finish it during the half-hour recess period after lunch. In most cases, the student will finish the work in 20 minutes and still get about 10 minutes of recess.

Recker, who doesn’t take away recess for disruptive behavior, said she and her co-teacher subscribe to a “compliance first” philosophy, under which students are required to finish one task before moving on to the next.

“We believe there should be natural consequences for things,” she said.

For about 80 percent of Recker’s 26 students, one recess spent completing classwork is all it takes to prevent students from wasting class time in the future.

“There’s probably just a handful of students who are pretty consistent because they choose not to do their work,” she said.

Recker, who is in her first year of teaching, believes concerns about childhood obesity are valid but said combatting that trend is not her primary job as a teacher.

“I don’t think missing 20 minutes of recess is that detrimental. I think going home and watching TV for three hours is worse.”

She also said she’s aware of the link between physical activity and academic performance, which is why she and her co-teacher do four “brain breaks” a day where the students do jumping jacks, push-ups or some other movement activity.

Implication of state law

Under state law, Colorado elementary schools are required to provide students with the opportunity for 600 minutes of physical activity a month, or about 30 minutes a day. Such opportunities can include recess, gym class, brain breaks or even field trips that incorporate physical activity.

Lisa Walvoord, vice president of policy for LiveWell Colorado, said while the law doesn’t prohibit withholding recess, “It would have to be very much implied.”

“If schools are seeing recess as the opportunity [for physical activity] and they’re taking that opportunity away, they’re not in compliance.”

Megan Murillo, a Pueblo mother of three and former Denver teacher, knows about the state law, but also wonders if it’s easy to skirt.

On a day where students lose recess, for example, she said school administrators might “come back and say, ‘Well, they had gym today.’”

Murillo said she encountered the recess issue last year when her daughter’s kindergarten teacher at Pueblo School for Arts and Sciences sent a note home saying students who were late to school would miss recess. This year, poor behavior sometimes lands kids “on the wall” for a few minutes of recess, but, on the flip side, the first-grade teacher adds extra recess as a reward too, she said.

Reiterating concerns voiced by Cara Marshall and other parents, Murillo worried that boys get recess taken away more than girls, losing a valuable outlet for their pent-up energy.

“Having a five-year-old boy now, I’m like, ‘Oh my gosh, he needs that,’” she said.

One school’s evolution

At Thimmig Elementary School in the Brighton 27J school district, recess has come full circle in the last several years. Today, the district’s wellness policy, which was updated last year, prohibits the removal of recess as a punishment or to provide extra work time.

But even before the policy was drafted, recess was evolving at Thimmig.

When Danielle Cole, a second grade teacher, started at the school a decade ago she said, “I was one of the teachers who took it away and had them sit on the curb or against the wall…I think it was kind of the norm back then.”

Eventually, Cole realized the punishment “wasn’t effective.” Instead, she tried having student who’d misbehaved walk or jog laps around the playground, but she and her colleagues nixed that consequence too. They found that the students doing laps became frustrated as they watched their friends play. Plus, the teachers didn’t want them to think of exercise as a punishment.

The recess story doesn’t end there. When Principal Justin McMillan started in 2008, he reduced recess by 15 minutes in the lower grades to provide more instructional time.

“I was that guy,” he said with a laugh.

Then in 2011, he attended the Healthy Schools Leadership Retreat in Keystone and said it became crystal clear how counterproductive that was. McMillan quickly reinstated the lost recess time.

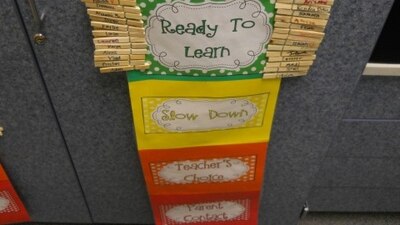

He said of the change, “You’re gaining instructional time because they’re coming back ready for learning.”