In an unusual step for districts facing a looming state accountability deadline, one rural district is completely overhauling its schools in an attempt to stave off state intervention.

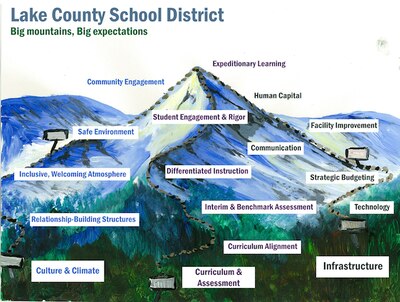

In an effort to reverse years of low performance, Lake County School District, a central Colorado district that serves a slightly higher rate of impoverished students than Denver, is in the first stages of moving entirely away from its traditional academic model in its elementary and middle schools.

The elementary and middle schools will be joining a national coalition of so-called “expeditionary learning” schools, which focus on high-level thinking and real-world ties to classroom learning. If that’s successful, district officials, with teacher approval, could bring the model to the high school in 2015-2016.

Lake County is among a number of struggling districts that the state has given a timeline to show dramatic improvement or face intervention. But, state officials and observers say, it is one of the first rural districts on that timeline to take a comprehensive, proactive approach to turnaround.

A new direction, and a host of challenges

Teachers at the district’s elementary and middle school say that the adoption of the expeditionary learning model is a much-needed shift in direction, but the road to get to that decision has been rocky.

Dan Leonhard, a third grade teacher at West Park Elementary, remembers that when he first joined the district three years ago, teachers used a patchwork of strategies and materials that failed to get students thinking at high levels.

“Everyone just worked their tails off trying everything they knew and throwing everything they could at these kids,” said Leonhard. “It changed across levels, across teachers the way it would be taught.”

After his first year, the school’s scores actually declined. So last year, the district’s new superintendent and Leonhard’s former principal Wendy Wyman made changing classroom instruction her priority, talking to teachers and trying to get at the root cause of the district’s low performance.

“We did a lot of walk-throughs of classrooms,” said Wyman. “One of the things we learned through that process is that we wanted more support for curriculum and instruction.” Wyman started by bringing in both state and privately-run teacher trainings and by sending teachers to other districts to see what was working — or not.

But she wanted to make sure that any major changes were tailored to the particulars of the community, which includes Leadville, a popular outdoors destination.

“[It was] about coming up with a process that really matches who we are in Lake County,” said Wyman.

She and school leaders started by making small adjustments, including hiring instructional coaches for the elementary schools and starting to adopt state exemplar curriculum.

But at first, the small changes just provoked more uncertainty for teachers. Teachers and the administration felt directionless as they tried one strategy after another.

“It was just ideas and ideas and ideas,” said Leonhard. “There was just kind of a cluster of things to do without a vision of where we’re going to be.”

Looking at the possibility

Many staff felt there were too many things that needed to be fixed to do it piecemeal; the district needed a wholesale, cohesive new direction. Several administrators, including Wyman’s replacement as principal at West Park, Stephanie Gallegos, had experience with expeditionary learning and raised it as a possibility.

Students at expeditionary learning schools spend six months to a year completing a comprehensive unit on a single subject, known as an “expedition,” that crosses academic fields and culminates in a trip to a relevant location or in a visit by experts to the classroom.

Gallegos said the model just seemed right for the district, because of Leadville’s mountainous location and the ability to pull in experts on real-world topics like mining and the ski industry.

Plus, “expeditionary learning has some of the best professional development I’ve ever had as a teacher,” said Gallegos. She made educating her teachers in the model a top priority, even personally covering their classes so they could visit other schools or participate in trainings.

The national organization that coordinates expeditionary learning schools requires that any school adopting its model get approval from its teachers. When it came time to get the teacher go-ahead, Gallegos and Wyman’s efforts paid off — teachers in the district’s elementary and middle schools voted unanimously to adopt the model.

“As soon as that was solidified, there was a huge sigh of relief,” said Leonhard.

Although the official rollout doesn’t start until next year, he and other teachers have already begun to use the curriculum and approach in their classroom. Leonhard tried out a mini-expedition last fall on the impacts of World War II on Leadville. Many teachers at West Park are already using the official math curriculum and they plan to work on the curriculum for English language learners next.

“Before, if you went to someone and said, ‘this is not working’, the response would be, ‘well then try something new,'” said Leonhard. Now, he said, a single approach gives teachers time to focus on improving their instruction.

“It keeps [students] thinking at a much higher level than we could get them to before,” he said.

The district is also partnering with the Odyssey School, a well-regarded expeditionary learning school in Denver, for teacher training and other supports.

Although that partnership is in the early stages, it may also spawn a solution to a perpetual rural dilemma: how to fill open teaching positions.

One potential idea leaders have floated would be for Odyssey to funnel qualified but unsuccessful candidates’ applications to Lake County.

“We have a wealth of amazing talent and rural districts need that too,” said Mary Seawell, who directs rural education initiatives for the Gates Family Foundation. The foundation (which is unrelated to the Microsoft founder) is considering providing funds to support Lake’s adoption of expeditionary learning.

Big strides, not baby steps

The total overhaul approach that Wyman and her team have taken is atypical in rural districts.

State experts say that’s because of a misguided belief that when districts reach the end of the accountability timeline or “clock,” anything they’ve tried will go out the window.

“If we’re two years away from the end of clock, we don’t want to make big changes” is the thinking, said Peter Sherman, who heads the state’s turnaround vision.

At the end of five years, districts that haven’t improved may face state intervention, so officials may be wary of investing a lot of resources into programs that might be thrown out later at the behest of the state.

“All of that leads to a lot of disincentive to make bold moves,” said Sherman.

Wyman has welcomed staff from the Sherman’s department to observe and provide guidance for her and her team. It’s an unusual move that Sherman said may improve their case in front of the state board, who will ultimately decide what the state’s role will be.

“A district like Lake [could] say to the board we’ve worked with your staff and we’ve remained nimble,” said Sherman. “All of those things will make for a strong argument for the board to say we have some fine-tuning recommendations but let’s not pull the rug out from under them.”

While that’s not a guarantee — Sherman said results are still important — he hopes it will encourage districts to try big changes.

Major overhauls may also attract attention and help districts pull in the resources many rural leaders struggle to access. Wyman’s overhauls have gotten attention from Denver-based organization including the Odyssey School, the Gates Family Foundation and Get Smart Schools, which is a leadership training program.

“We really believe this is a great district to work in,” said Seawell. “They have a plan and need the resources to do it correctly.”

Her proposal, which she will put to the foundation’s board, includes an advisory board that would pull representatives from Get Smart, Odyssey and other expeditionary learning organizations to provide guidance for Lake’s reforms.

For Seawell, it could be a model for how Front Range foundations can support other rural turnarounds, which generally get minimal outside support.

“It’s not someone coming into save a rural district,” said Seawell. “It’s a symbiotic relationship.”

Success not guaranteed

Still, no one has seen the data yet to see if the shifts are working. Teachers and school leaders are optimistic that their efforts will make a difference but worry about whether they’ll get the chance to do things right and whether they’ll see results.

“The highest level of concern that the staff has is, if we do this, are we sticking to it?” said Leonhard. “Education is infamous for having a flavor of the month.”

As a way to ward off that possibility, Wyman has made efforts to involve the community in the turnaround effort, including reaching out to the Hispanic community from which the district draws the majority of its students. Wyman is studying districts like Roaring Fork that have some success with outreach and has spent time visiting with community groups in attempt to build goodwill.

“If we’re going to get off of turnaround and be the kind of schools we want to be, it’s important for the community to be right there with us,” said Wyman.

But after years of low performance, many are just watching to see if it works.

“There’s a lot of skepticism,” said Amy Morrison, a parent who has been involved with the district accountability committee. Many parents in Leadville send their kids to Eagle County schools or south to Buena Vista, and Morrison isn’t sure if they’ll come back to the district.

But if it does work, Morrison thinks other communities may follow in Lake County’s footsteps.

“If we can work together, if we can be positive, maybe we can become the model,” she said.

Gates Family Foundation is a Chalkbeat Colorado funder