A growing awareness that perennially high teacher turnover is hurting student learning is prompting Denver Public Schools to seek the root causes of churn and develop strategies to keep teachers in the classroom.

More than 20 percent of all DPS teachers left their positions between 2012 and 2013, according to state data. And according to district information, half of all teachers leave the district within three years.

“Right now, our teacher turnover, in particular in high-poverty schools, is a problem,” said DPS superintendent Tom Boasberg. “Nothing is more important for closing achievement gaps than being able to have our best teachers and our best school leaders working at and staying at our high-poverty schools.”

Denver Public Schools released a report last week highlighting recommendations for reducing turnover, especially in high-needs schools. The district has also started tracking voluntary teacher turnover in schools to determine when and where teachers are leaving for reasons other than retirement or advancement.

The quality of leadership, an unsustainable workload, and too much assessment were among the factors the task force of teachers behind the report identified as leading to high turnover.

At Kunsmiller Creative Arts Academy, teacher Martha Burgess said that each teacher’s decision was different. “It’s different factors over time: People not feeling respected, not feeling like they’re making an impact. Certainly workload,” she said. “Some retire, some transfer to other schools. But it is important. When you look at what veteran teachers bring, that can’t be underestimated.”

Keeping teachers in the classroom

Denver’s difficulty retaining teachers is part of a statewide trend: A fifth of all Colorado teachers left their positions between 2012-13 and 2013-14, according to the state Department of Education. That’s higher than the national turnover rate of 14 percent.

Statewide, “turnover is at crisis level,” said Shelley Zion, the director of the Center for Advancing Practice, Education and Research at the University of Colorado Denver. The university has also recently launched a program called EDU focused on supporting teachers and reducing turnover.

But the fixes on the table aren’t always simple. “If we want to retain really quality teachers, we need to really shift how we empower and support them to get what they need,” Zion said.

The DPS teacher retention report was based on the work of a group of district teachers, most of whom work in low-income schools. In Denver, teachers who do stay in the classroom tend to transfer to schools with lower poverty rates.

The recommendations fell into four themes: Leadership, supports for students, supports for teachers, and rewards and recognition.

- Leadership: The panel recommended a clearer process for hiring principals, including a teacher voice in that process; having principals teach a class each week; and requiring principals to be master teachers. (The district has recently launched a number of programs focusing on preparing and supporting school leaders.)

- Support for teachers: “Put simply, the workload at high-poverty schools is unsustainable,” the authors wrote. “…As it stands…the number of assessments required coupled with the absence of adequate planning time…render teaching in high-poverty schools less attractive.” The panel also urged the district to decrease the teacher-student ratio.

- Support for students: The task force called for provide more resources in high-poverty schools, including hiring enough counselors, school nurses, and parent liaisons.

- Rewards and recognition: The report suggested creating clear paths for teachers to grow professionally, and financial recognition for teachers who take on new roles, and those who stay in high-poverty schools for longer stretches of time.

In a public email, Boasberg said the district would heed the task force’s advice and was already taking steps to address the issues it raises. And in an interview, Boasberg said that the district also planned to adjust its ProComp system, which offers financial incentives to teachers who work in high-needs roles or schools, or who accomplish certain objectives, to make it more effective. The district is currently negotiating an update to ProComp with its teachers union.

Baby steps

This school year, DPS officials started using high rates of voluntary teacher turnover as a “flag” that that school may need support or more attention.

At a meeting of the district’s board last November, DPS Chief Academic Officer Alyssa Whitehead-Bust mentioned turnover as one of the non-academic factors the district uses to gauge school quality. “We know in schools that lack stability, it’s so much harder to improve student outcomes,” she said.

But even as the district looks to reduce turnover, some of its strategies for struggling schools involve replacing staff or entire schools. One teacher, who requested anonymity because she said she feared retaliation, told Chalkbeat that the lack of job security at high-needs schools had influenced her own and peers’ decisions about where to work.

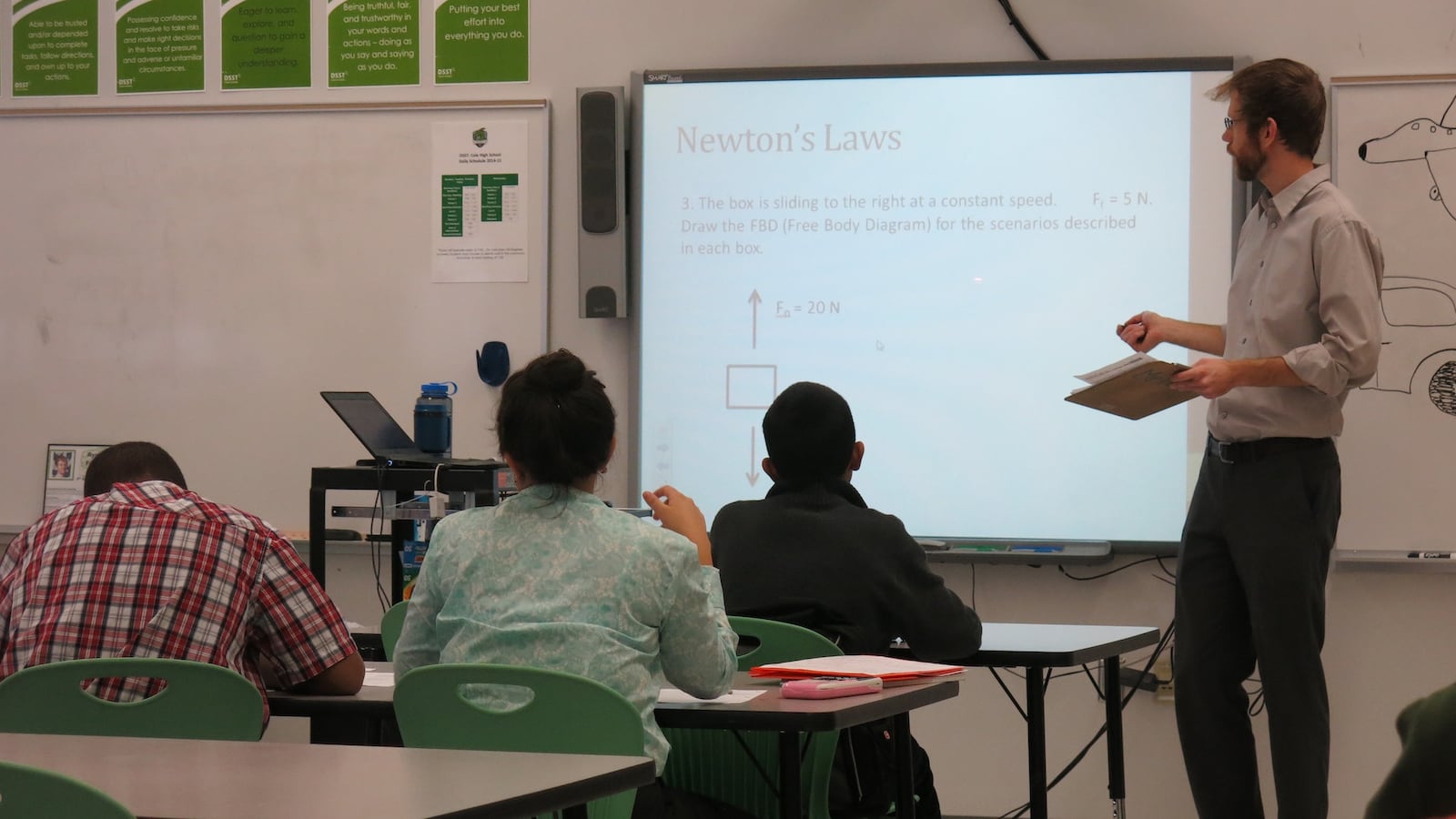

Some of the district’s charter schools are independently examining their own teacher retention and satisfaction. Charter network DSST, for example, has made teacher fulfillment one if its strategic priorities for the current school year.

Beyond “Hoop Jumping”

Teacher fulfillment and satisfaction—or the lack thereof—also drove the creation of EDU, said the University of Colorado’s Zion. “The big idea behind it has been that teachers in the last several years have been disempowered, scrutinized, deprofessionalized and stressed beyond measure,” she said.

EDU members, who can come from anywhere, pay $20 per month to access a set of courses and resources, online and physical, that address both the pedagogical, professional, and social-emotional elements of teaching.

“We in teacher education feel like we do a really good job of preparing them,” Zion said. “But then they go into district schools and classrooms in which they’re sometimes supported well, but often not.”

At Kunsmiller, teacher Mandy Israel said outsiders often underestimate teachers’ workload and emotional commitment. “I get here at 7. The contract doesn’t say I have to get here at until 8:30. And when I get here there are other people in my hallway who are already here.”

Israel is now a teacher-leader at her school—a role that she says has increased her professional satisfaction but added to her workload.

Burgess said she had been reflecting on why teachers leave schools after encountering an editorial by Josh Waldron, who had been named Teacher of the Year by a local group in Virginia only to leave the profession several years later.

In the editorial, Waldron writes that teaching in his district had become unsustainable financially and personally. His top concern at his district was what he describes as “hoop jumping”—adjusting to a constantly-shifting and time-consuming set of requirements from the district.

Burgess, also a teacher-leader, said that in her sixth year teaching, she still enjoys teaching but empathizes with Waldron’s concerns. “I’m excited that there is finally some attention being paid,” she said.