Denver Public Schools is intensifying efforts to ensure that charter schools are serving their fair share of special education students by transferring some centers for students with severe needs from district to charter schools.

This is one of the first systemic efforts in the country to address a long-standing concern about charter schools’ special education services.

As the number of special education programs in charter schools grows, officials here have encountered questions about funding, placing, planning, overseeing, and sustaining programs.

The transition to charter programs began in 2010 with an agreement known as the district-charter compact, in which DPS and charter school leaders agreed on strategies to make sure charters and district schools are serving students equitably.

DPS currently has 132 centers in district and charter schools combined. They serve approximately 1,300 students.

During the current school year, nine charter schools enroll 58 students in K-12 center programs. Next year, 15 charter schools will have programs for an estimated 107 students. In five years, 40 charter schools centers will enroll 300 students—a number intended to mirror charters’ share of overall student enrollment. (The district and several charter schools have additional special education programs for early childhood students and students older than 18.)

In Denver, as in many school districts, charters as a group are less likely to enroll special education students than district-run public schools. Students with more severe needs are the least likely to attend charter schools.

“When we look at enrollment, about 11 percent of DPS students have special needs. In charters, it’s closer to 9 or 9.5 percent,” said Josh Drake, the district’s director of strategic initiatives. “A lot of that difference is made up of kids with significant disabilities.”

Most charters have not historically had services in place for students with uncommon or severe special needs. Students who applied to charters would be referred to district schools with special self-contained classrooms known as centers.

New Orleans, which held a competitive grant program to encourage schools in its nearly all-charter system to work with special needs students, is the only other large district that has made a system-level effort to address special education gaps, said Robin Lake, the director of the Seattle-based Center for Reinventing Public Education. The center is a research and policy group that studies urban school districts and charter schools.

Lake said that while the effort would help address inequities in where special education students go to school, “the bigger opportunity is if a charter school with all its flexibilities can find a new, innovative way to serve kids that are often really challenging to figure out how to serve well.”

But schools and the district must balance efforts to innovate with their legal requirements to meet students’ special needs.

“I think to the extent that they’re trying to make both types of schools fully accessible, it’s laudable. But like everything, the devil’s in the details,” said Julie Mead, a professor of education policy who focuses on special education at the University of Wisconsin, Madison.

“The idea is that the school itself has more autonomy in how it delivers curriculum,” Mead said. “How does school autonomy fit in with this issue?”

Phasing out

Many of the center programs are being “phased out” a year at a time from their existing schools and “phased in” to the new charter schools. That’s the plan at STRIVE Excel, a two-year-old school, which will add 10th, 11th, and 12th graders to its current 9th grade class as a similar center is phased out of North High School. The two schools share a building.

Nicole Veltzé, the principal at North, said she pushed for STRIVE to take on the program when plans to co-locate the two schools were being discussed.

She said that while 162 of North’s 923 students have severe needs and are enrolled in center programs, STRIVE had had none until this year, when it opened a center for nine of its 239 students.

“It’s still disproportionate, but it’s definitely a step in the right direction,” Veltzé said.

STRIVE Excel principal Kate Berger was enthusiastic about the new program. She said working with students with special needs, including the center program, is a passion of hers and one of the things that had drawn her to STRIVE.

“The fact that we work in collaboration with the district and the fact that charters in Denver are held accountable to serving all kids is something that’s so important to me,” she said.

Working with severe needs

Students are placed in center programs when their Individualized Education Plans, or IEPs, indicate that they are best served by spending the majority of their time outside of the traditional classroom. DPS has centers for groups including students who are deaf, students with autism, students with serious cognitive and physical challenges, and students with behavioral and emotional needs. The programs are not offered at every school, so students are generally assigned to the nearest program that fits their needs.

Over time, the district is moving more students out of centers and into more traditional classroom settings when possible, said DPS’s Drake. The belief is that it is beneficial for the students with special needs and their peers to be in a more inclusive environment. In 2009-10, 2 percent of DPS students attended center programs. That’s down to 1.5 percent this school year.

But some portion of students will always need center programs, said Diann Richardson, the district’s director of special education.

Such programs are space and money-intensive and require significant expertise. That’s made transferring them to charters a challenge.

Drake said DPS first had to sort out how much money charter schools should get to fund the programs. Then it had to find space: Some small charter schools don’t have an empty classroom to dedicate to a center program.

Meanwhile, the schools have to find appropriately skilled staff. While most charter school teachers are not required to have to have a traditional teaching certificate—they can instead be designated “highly qualified” through a combination of test scores and college coursework—special education teachers are required to be certified.

There’s also the question of oversight and accountability for programs serving some of the district’s neediest students.

Charters that host a special needs center get a boost on the Denver’s School Performance Framework, used to evaluate schools. Some students in the centers take an alternative assessment, while others take regular standardized tests.

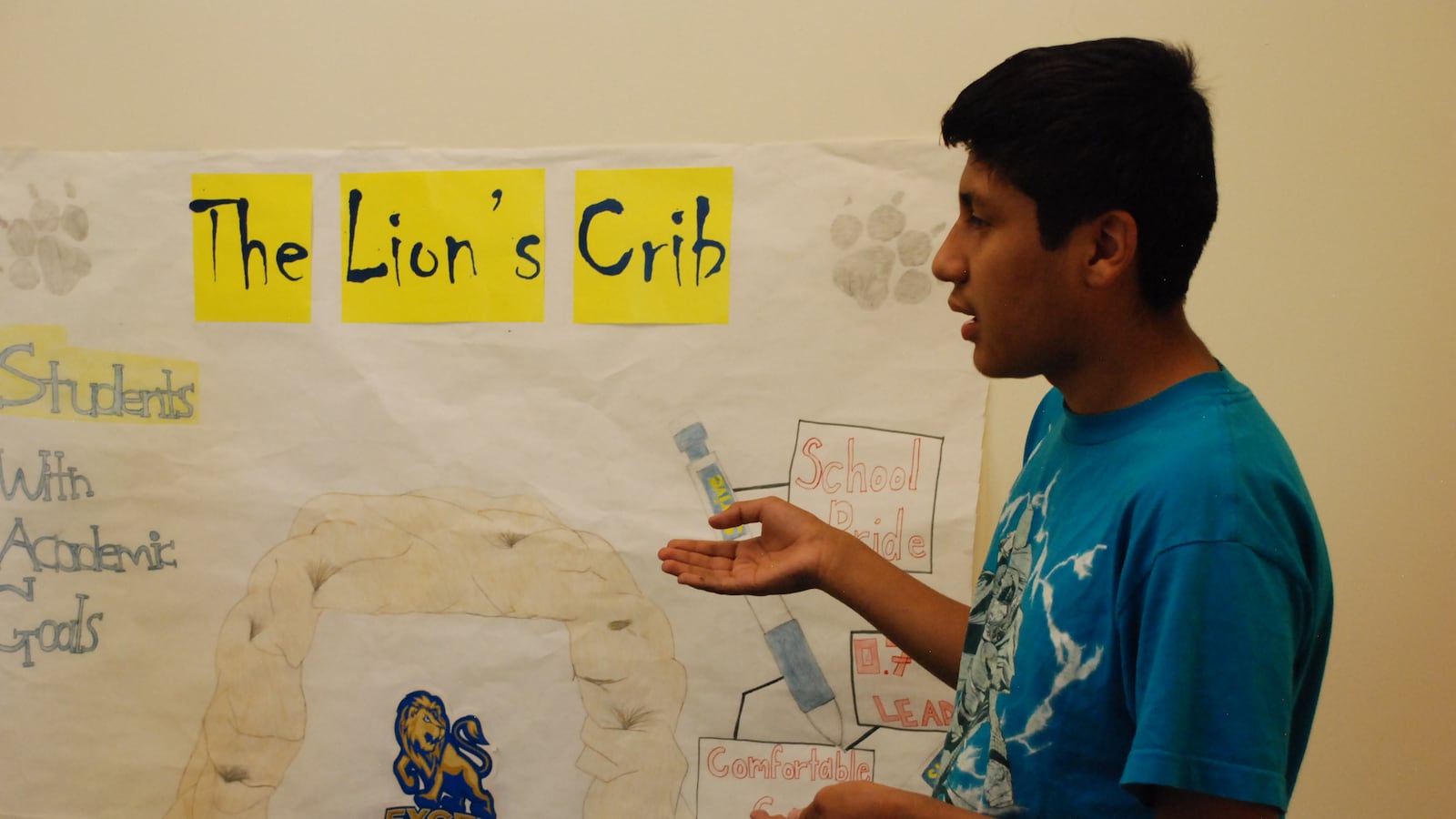

The schools can design their own programs. At STRIVE Excel, for instance, school staff said that they had researched center programs at district schools but developed their curriculum and schedule in-house. The school hired a teacher who had not previously been at DPS to lead the program and budgeted for extra paraprofessionals.

But the district’s special education department helps the schools plan, and oversees the programs more closely than it does most other programs at charter schools. That’s because DPS is directly responsible for special education services in district and charter schools under federal law.

Drake said Denver families will always have at least one center option that is not at a charter school. For some, however, the nearest and most convenient program is already at a charter.

Planning centers in a changing landscape

One of the first charter schools to start a center program was SOAR at Oakland, a charter school that had taken over a low-performing neighborhood school that already had centers.

Marc Waxman, the director of SOAR, said that the center programs had been a point of pride. “We worked very collaboratively to create our own vision and version of what the center program should look like that met all the requirements of DPS,” Waxman said.

He said SOAR had hired a full-time speech and language pathologist, partnered with a local private school, and increased the training and professional development given to paraprofessionals. The school also assigned an administrator to work on the centers half-time.

But those changes were short-lived: SOAR surrendered its charter back to the district after two years, for reasons unrelated to special education.

In a district like Denver, where closing and opening schools is a regular occurrence, that instability is “a risk,” said Drake. “We’re not wanting to start a program in a school that’s still working through instability.”

“But to be honest or blunt, we have that risk with district-run schools too,” he said. “Kepner has two center programs, and Henry, too. We face that with all school types.” Both Kepner and Henry are district-run middle schools being “phased out.”

STRIVE

Chris Gibbons, the director of the STRIVE network of schools, said that his organization has placed an emphasis on special education in general, not just at the centers. Gibbons said the issue is close to his heart, as he has a brother with Down Syndrome.

Three of STRIVE’s nine schools now have center programs, and a fourth will open one next year.

“It’s mission-critical for us that we’re opening neighborhood schools that truly serve all kids in the community,” he said. “What’s particularly striking is that general education students have embraced the program as being a core part of the school.”

STRIVE’s process for integrating the centers has changed over time. The first, at Lake, had been added as part of taking over an existing school. Schools planning to add centers now hire staff a full year before opening.

Gibbons said that while he is optimistic about the programs, he is concerned that the district doesn’t have a systematic plan for placing them yet. “It’s been made on a one-on-one basis so far. I think it’s reflective of collaboration, but I worry a little about the system and structure going forward,” he said.