Last year at preschool, Madison Walker would stomp her foot when she got upset. When her teachers sternly told her there would be no foot-stomping in the classroom, she simply stomped harder.

It was a power struggle with no victors.

Madison, who has autism, was miserable at school. Her teachers were frustrated, ultimately telling her mother, Kristin Miesel, that the girl might have to be physically removed from the classroom if her emotions continued to escalate.

Miesel, a school psychologist at a Jefferson County elementary school, chokes up remembering that moment.

“It’s like, ‘Really? You need to physically remove my child because she’s stomping her feet or getting upset like that?’” she said.

Fast-forward a year. Four-year-old Madison (a pseudonym to protect her identity) now attends preschool at Bal Swan Children’s Center in Broomfield, and Miesel has finally breathed a sigh of relief.

“This place is like heaven,” she said.

The center, where about one-third of children have special needs, uses an approach that Miesel and school leaders credit with creating a welcoming environment for every kind of child—even those who elsewhere might get kicked out for biting, hitting or other behaviors.

It’s called the Pyramid Plus Approach and launched six years ago at four demonstration sites in Colorado, including Bal Swan. Today, it’s used at around 200 centers and preschools in the state.

While the program has grown slowly but steadily since 2009, it’s getting a closer look in light of recent state and national conversations about the alarming frequency of preschool expulsions.

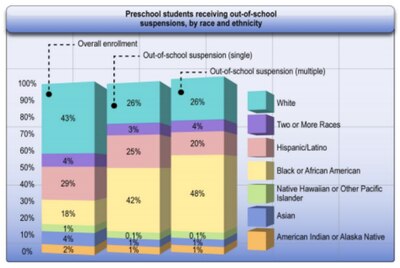

Not only are preschoolers expelled at higher rates than their K-12 counterparts, a 2014 report from the U.S. Department of Education revealed that boys and students of color are disproportionately expelled from preschool.

Geneva Hallett, director of the Pyramid Plus Center at the University of Colorado Denver, said getting expelled at 3, 4 or 5 often leads to a lifetime trajectory that includes more of the same.

Bal Swan Director of Education Patti Willardson calls preschool expulsion her hot-button issue. She finds it frustrating that the default response to challenging children at some local centers is to send them to Bal Swan.

“We take as many kiddos as we can,” she said. “But I just keep telling other administrators, ‘You can’t depend on one school in the whole area to take these kids. You all need to learn to help them yourself.’”

A Full Toolbox

The Pyramid Plus Approach was created in Colorado, building off a free national framework for early childhood social emotional practices called the Pyramid Model. More than 24 school districts have adopted that model over the last eight years with support from the Colorado Department of Education.

The “Plus” in Pyramid Plus refers to its emphasis on including children with disabilities in early childhood classrooms.

Pyramid Plus includes an 18-session training and follow-up coaching. The idea is to give early childhood staff a full set of tools for teaching young children social-emotional skills and managing challenging behaviors.

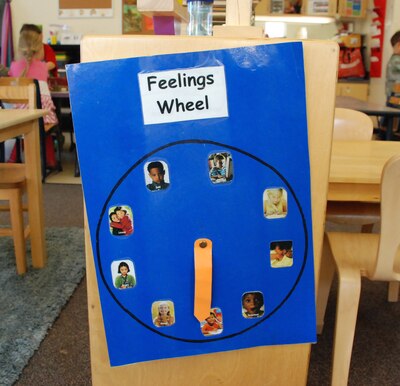

For example, teachers might learn when to ignore bad behavior so as not to reinforce it with a burst of attention. Or how to use puppets to demonstrate toy-sharing or teach students to be aware of their own emotional state.

At Bal Swan, you won’t typically hear admonishments like “no,” “stop,” or “don’t.” Correction is rephrased in a positive way. You’ll also see teachers using the same social skills they tell students to employ, like getting someone’s attention with a tap on the shoulder.

Pyramid Plus also includes a series of parent classes called Positive Solutions for Families that offer many of the strategies and tools that teachers use in the classroom. Miesel said even with her background as a psychologist, she’s learned a lot from the sessions.

“The language they use here has been educational for us,” she said.

The Pyramid Plus Approach is not the only program aimed at cultivating healthy social-emotional development in young children, or the only one cited as a remedy to preschool expulsions. Another evidence-based program called The Incredible Years, run by the Denver-based Invest In Kids, provides similarly themed trainings to teachers and parents.

Early childhood mental health consultants, who are typically called in to help teachers work with the highest needs students, represent another expulsion prevention strategy, but their ranks are relatively small in Colorado.

Diminishing problems

Using Pyramid Plus doesn’t mean that aggressive or disruptive behaviors magically disappear. They may occur less often, but many Pyramid Plus advocates say the biggest transformation is in the level of confidence teachers display when problems do arise.

“When they have a plan and they know they can deal with these things. They don’t see challenging behavior as a problem anymore,” said Alyson Jiron, a Bal Swan counselor.

“It’s not like there’s kids that people are like, ‘Oh I don’t want that kid in my class,’” she said. “Truly, across the board now … everyone’s like, ‘We got this. We can do this.’”

When a child recently jumped up on a table in the class Clarissa Villareal co-teaches, she ignored the behavior and instead focused her attention on a child nearby who had her feet on the floor. The table-stander soon got down on her own.

“A huge part of it is our reaction,” she said.

At Bal Swan and other centers that use the Pyramid Plus model, expulsion isn’t an option. In fact, providers sign an agreement beforehand stating they won’t resort to it.

Hallett said without that policy, expulsion could be a tantalizing option when the toughest cases rear up.

“That’s not a back door they can get out of…and that’s hard,” she said.

Slow build

While there are now 2,200 providers trained in the Pyramid Plus approach in Colorado, that represents only a fraction of the state’s early childhood workforce.

“It has been a slow steady build,” said Hallett. “The fact is this is very hard work.”

Pyramid Plus, which includes a 45-hour training costing up to $500 per person, can be a tough sell for time-crunched, cash-strapped childcare centers.

Elizabeth Steed, an assistant professor at the University of Colorado Denver, said she’s visited hundreds of preschool classrooms and many don’t have the budget, leadership or staffing flexibility to take on the program.

“They feel very stretched already,” said Steed, who is a member of a state policy team promoting the Pyramid Model and inclusion practices.

Bal Swan, named for a philanthropist who donated to the school, is perhaps better positioned than smaller, less stable centers to embrace an effort like Pyramid Plus. Most of the school’s 350 slots are tuition-based. In addition, class sizes are small and the pay is above average. Willardson said teachers with a degree typically start at $18 an hour and go up to $23 — at many centers it’s closer to $13-14 an hour.

Thriving

These days, Miesel doesn’t brace herself for bad news when she picks up her daughter at the end of the day.

Even when Madison slips up, she knows its not a stepping stone to ultimatums or expulsion.

Take, for example, a recent day when Madison bit a classmate.

There were no gasps or scoldings. Instead, a teacher consoled the injured child and then enlisted Madison’s help to get an icepack and deliver it to the girl. Instead of being punished for hurting her friend, she was praised for helping her feel better.

Miesel admits she was mortified when she found out what happened, but Madison’s teacher and Willardson counseled her against overreacting.

“Don’t feed into it,” they told her.

While such a low-key reaction from teachers and parents can feel counterintuitive, it’s effective, said Willardson.

That’s what she likes about the Pyramid Plus approach.

“It’s changed our teaching skills … It’s changed our understanding of who children are,” said Willardson.