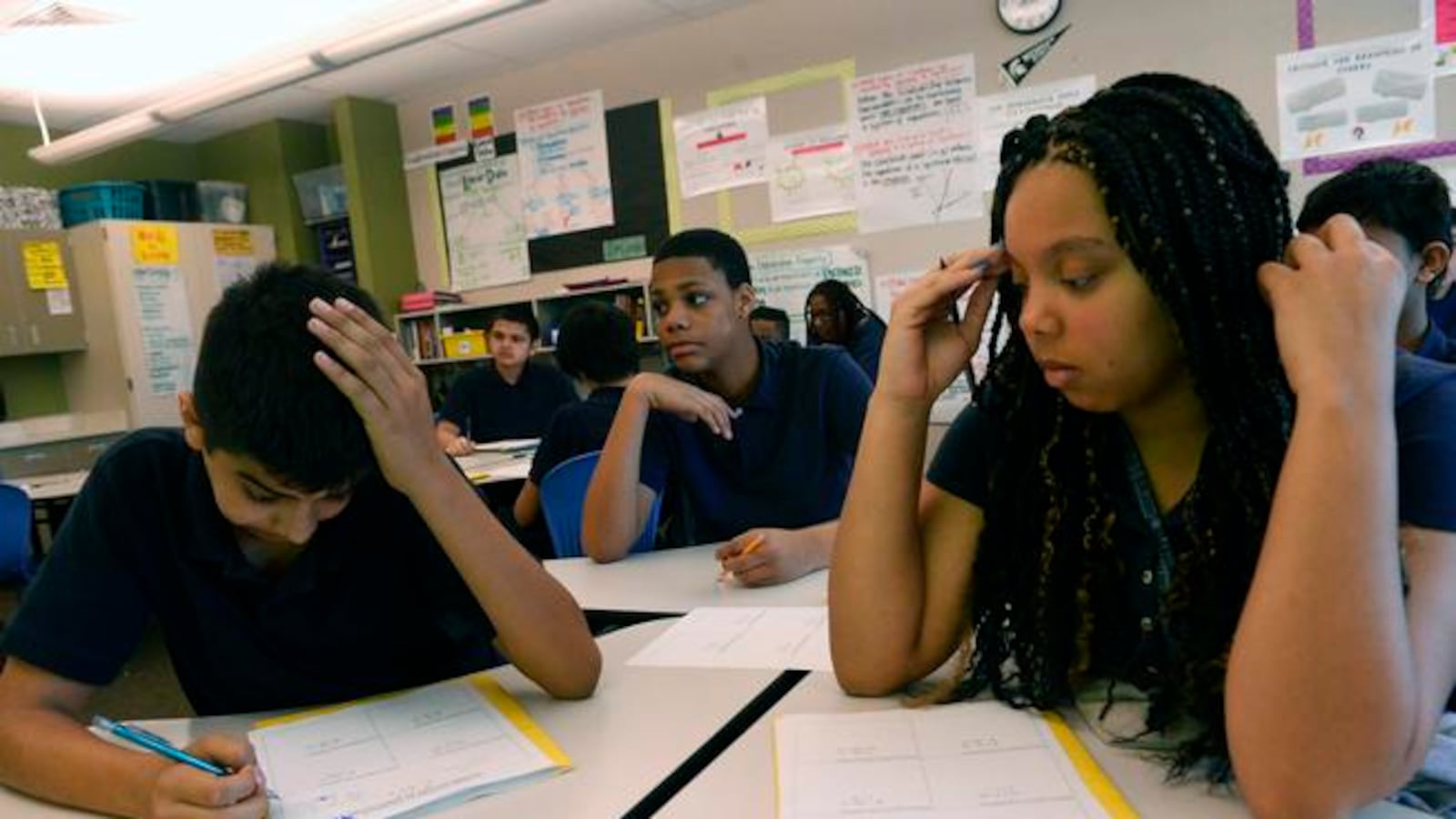

One Aurora school’s latest improvement strategy — built around fostering a positive culture and changing how kids are taught to write — could be paying off.

Boston K-8 on Tuesday received praise from district leaders as newly released state data showed student growth on English and math tests ranked among the highest in the district.

Middle schoolers at Boston had a median growth percentile of 80 in English. That means that on PARCC English tests, students showed improvements on average that were better than 80 percent of Colorado kids who started with a similar test score. Boston middle schoolers’ median growth percentile was 70 in math.

“We’re very, very happy with our growth and we want to see much more,” Ruth Baldivia, principal of Boston K-8 told the school board Tuesday. “We’re not happy with where we’re at, but we are happy with where we’re going.”

Though Boston showed big growth gains, its students are still far below where they should be to meet state academic standards. Only 20.5 percent of Boston seventh graders met or exceeded expectations on English state tests last spring, according to previously released data. Of eighth graders, 51.2 percent did.

Boston K-8 is one of five schools that are a part of Aurora’s new innovation zone, the district’s latest attempt to get students up to grade level. By receiving innovation status, the schools can gain flexibility from some state, district and union rules.

Most Boston K-8 students end up at Aurora Central High School, which is also part of the innovation zone but fared poorly on the latest growth report. The high school ranked among the lowest in the district in English test score growth and is likely to face state sanctions this year after years of low performance.

Baldivia, who took over Boston K-8 last school year, said the continuing changes from the reform plan are only building off work that started last year.

“We had already known and we had already felt a difference,” Baldivia said. “This thing that teachers helped create, we’re going to continue to do because it’s good. We’ve got the proof now.”

Last school year, the school adopted a new writing curriculum and took advantage of its innovation status to carve out new joint planning time for teachers.

For the first time, the school’s four seventh and eighth grade teachers worked together to design writing lessons for not just English class but for science, social studies and math, too.

Students also took a lead, Baldivia said, in new morning meetings. To create a more unified and open culture, students lead the discussions and start each day by giving shoutouts to their peers for things such as helping them with homework.

The school’s elementary school didn’t do as well in the latest state test report. In English, the growth was 38. At a board meeting Tuesday, district staff presented the school’s elementary and middle school data combined, which put Boston K-8 in third place out of the district’s top 10 schools in growth.

School board member Dan Jorgensen explained to other board members the meaning of growth data, and said district numbers showed Aurora schools falling behind other districts. Overall, Aurora Public Schools got a 47 in English and 46 in math.

But he called Boston’s numbers “impressive.”

“For our kids to get where we want them, we need growth percentiles of 60, 70, probably 70 plus,” Jorgensen said. “If you’re around that median and definitely below it, you’re not really on track.”

John Youngquist, Aurora’s chief academic officer, said in a statement, that growth is a good measure of progress toward improved achievement.

“Both growth and achievement are of value,” Youngquist said. “Growth is an indication that current efforts are gaining traction and that students are engaging in learning at higher levels. The ultimate goal is to improve achievement overall.”

At Tuesday’s board meeting other school principals that made the district’s top ten schools shared what they believed helped them reach those high numbers. Among the reasons they cited: a data room where teachers talk about each student who needs extra help, training teachers how to teach kids to read and embedding core curriculum in projects across all classes.

Several also said it was simply about believing every kid could improve.

“I don’t want Boston to be the bad school. These are not bad kids,” Baldivia said. “They have not gotten the instruction and the support that they need and that’s what we want to figure out now and that’s why we’re here.”