Lyette Olson’s fifth-graders have no trouble telling their teacher she is wrong.

On a recent snowy Thursday morning, Olson gave her 23 students at Peoria Elementary a string of numbers to be multiplied and added — and provided what she said was the answer.

Her students caught her errors and told her she was incorrect. But Olson doubled down and insisted she thought she was right, asking them to explain their reasoning.

“Get your arguments ready,” Olson told her students. “You need to prove me wrong.”

Olson’s goals — to teach students that mistakes happen, work needs verification and answers must be justified — is part of a significant change in math instruction in Aurora Public Schools.

Olson is one of 28 APS teachers this year piloting different curriculum materials meant to boost student understanding of math through deeper thinking to meet higher state academic standards. The overhaul in the test classrooms is so far showing positive signs, officials say.

Math usually gives students across the state, including in Aurora, more trouble than reading. When Colorado adopted new academic standards five years ago, the gap between what was being taught in Aurora math classrooms and the new expectations was big.

Science and social studies resources were replaced in the last few years to align to standards, but it was done bits at a time. For reading, Aurora officials worked with their existing materials but added some extra and paid for teacher training. But in math, district officials found going that route wasn’t enough.

When teachers pieced together lessons using different resources, it created gaps. Students moving from one grade to another arrived in classrooms having learned different amounts of the content they’re expected to know, depending on who their teacher was.

Olson said as an example, the new fifth-grade standards asked students to know multiplication of fractions, but the existing curriculum only had about two days’ worth of lessons on multiplying fractions for fifth graders. Teachers had to independently look for more worksheets or lessons and had to vet if they were rigorous enough or if they aligned to the standards.

Now the goal is to free up that time for better use.

“Their time and energy and thinking will go into designing personalized lessons for kids in their class,” said Jim Hogan, a math instructional coordinator. “Resources don’t just magically up scores, but were looking at resource and instruction.”

According to 2015 PARCC test data, 13.7 percent of Aurora fifth graders in 2016 met or exceeded expectations in math, up from 11.2 percent in 2015. Statewide, 34.3 percent of fifth graders met or exceeded math expectations in 2016 up from 30.1 in 2015. Hogan said district officials expect to see the Aurora numbers keep climbing.

Both curriculums that Olson is testing — Bridges and Investigations 3 — have more lessons than she needs, she said.

“It’s better than not having enough,” Olson said. “And we’re all picking from lessons that are aligned.”

Instructional coordinators and district officials are visiting classrooms and tracking test data to see how kids are learning. In February, staff will make a final pick on which curriculum is best and ask the board to approve it.

Along with choosing the books or teaching guides, district staff are working to figure out how to more widely replicate the help they are giving teachers in the pilot.

Training in the pilot also emphasizes building a classroom culture that gets kids invested in math.

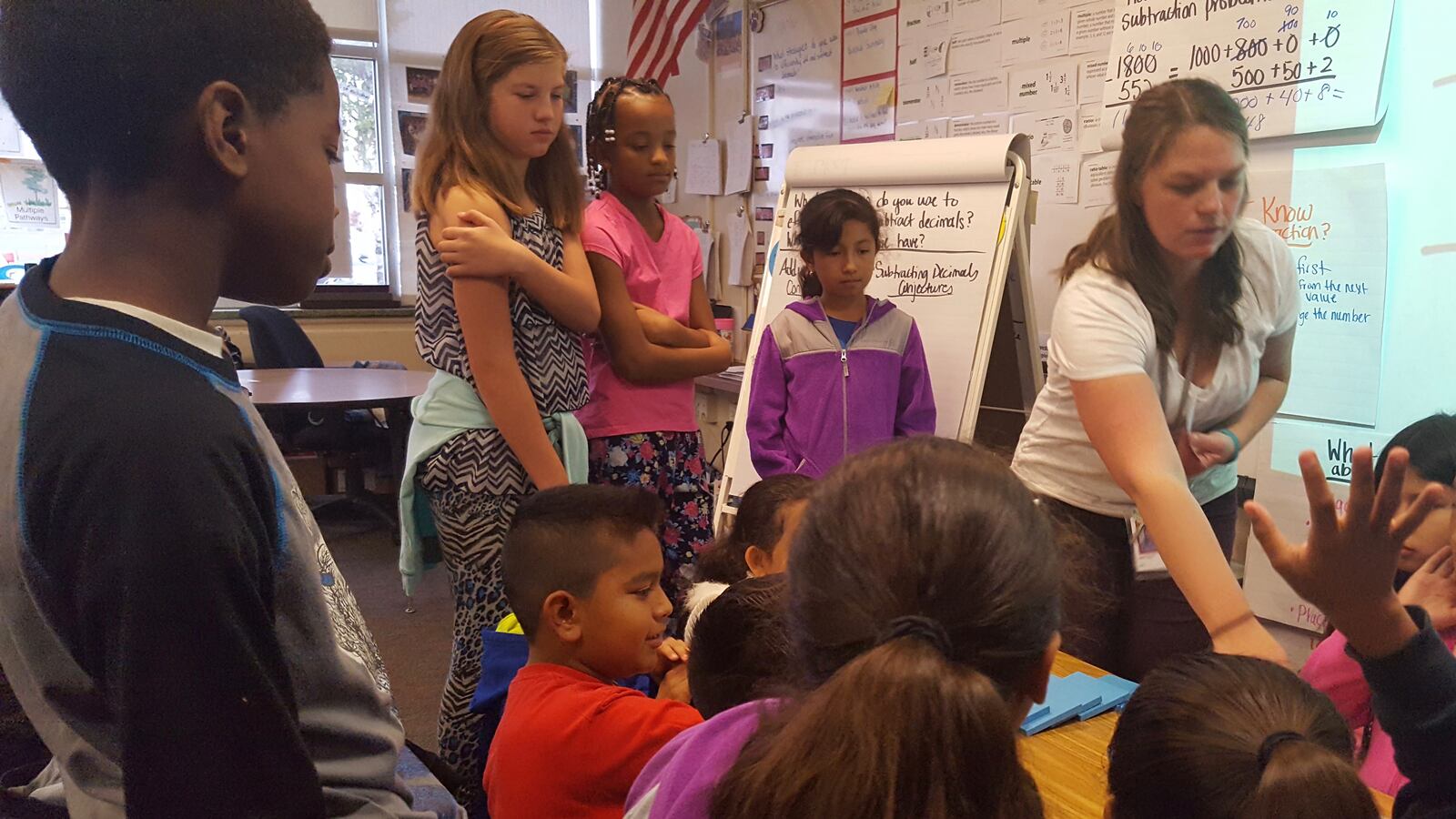

During that class last Thursday, the students talked about why place value matters and how to order numbers when solving problems. After practicing a few problems, the class gathered to talk about how it went. One boy raised his hand and independently volunteered that he had made a mistake when lining up numbers. He showed his mistake to the class, something that many students might want to hide.

Olson said the emphasis on culture has made a huge difference. “My planning is very particular to that,” she said. “My students can talk about math. They’re more aware of what they’re doing.”

Olson said she wants to make students comfortable with making mistakes so they don’t quit or think they’re bad at math because they don’t get it right at first.

“Those ideas are not completely gone,” Olson said. “But they’re starting to shift their thinking to this middle ground.”

Besides the summer training, instructional coordinator Kristen Gundel has visited and observed Olson’s class at least five times so far this semester. She uses a rubric designed by the pilot teachers over the summer to look for evidence that students are learning and afterward she talks with Olson about what she saw.

“Do students say a second sentence spontaneously?” Gundel said. “If a kiddo is doing this it suggests they’re thinking mathematically.”

District observers also notice that students in Olson’s class sometimes answer questions without raising their hands. They may at times get loud and excited. Some stand up to stretch their hand higher in the air and can’t wait for the teacher to call on them. It’s a good sign.

“It’s based on a realization that research is clear that mathematics is a language-rich subject,” Hogan said. “Students need rich discussion to learn and it’s a math standard now. There has to be a level of discussion.”

District administrators are asking Olson and other pilot teachers what training or feedback was necessary as they plan similar help for all teachers.

“We will not be successful if we just hope that teachers learn by accident,” Hogan said. “That’s the work starting right now. We’re trying to figure out what do principals need to understand? What do district leaders need to understand?”