In the most diverse city in Colorado, school district officials have struggled to hire and retain principals of color.

The issue isn’t unique to Aurora Public Schools. But one change made three years ago to how Aurora hires principals is now slowly increasing diversity among school leaders, officials say.

The revamped hiring process wasn’t aimed at increasing diversity, but rather at increasing quality and minimizing biased or preferential hiring decisions, officials say.

“Systems that are more likely to have bias are less likely to have diversity,” said John Youngquist, Aurora’s chief academic officer. “Systems that are engaging these kinds of processes that allow people to demonstrate behaviors they’ve practiced over time are ones that allow those high quality candidates to get to the top. I know is this is a practice that increases the level of diversity.”

This fall, 10 percent of Aurora principals are black, and 14 percent are Hispanic, up from 9 percent that were black and 7 percent that were Hispanic last year.

It’s an improvement, but the numbers still represent a gap with the diversity in the district and in the city. Eighteen percent of Aurora Public Schools students are black and more than 50 percent are Hispanic. The city of Aurora has similar demographics, according to the most recent U.S. Census estimates.

State data tracking both principals and assistant principals by race showed the Aurora district had lower percentages of school leaders who were black or Hispanic in 2016 than in 2013. Numbers for the current school year are not yet available.

This year, the numbers of teachers who are not white are smaller and farther from representing the student or community demographics than they are for principals.

Research has shown that students of color benefit from having teachers of color. Having diverse and highly qualified principals helps leaders in turn attract and hire high quality and diverse teachers, Youngquist said.

Aurora superintendent Rico Munn said that increasing diversity is a priority but said he isn’t sure how many educators of color Aurora schools should aspire to have.

“For our workforce to mirror the community, I don’t know that there’s enough educators in the state,” Munn said.

Elizabeth Meyer, associate professor of education and associate dean for undergraduate and teacher education at CU Boulder, said all districts should be striving to see an upward trend in the numbers, not necessarily trying to reach a certain percentage as a goal.

She said that issues in diversifying teachers and principal pools are similar, but that teachers of color who are supported can be the ones who can then go on and become principals.

“We’re already limited because teaching demographics are overwhelmingly white women,” Meyer said. “We do need to find ways to make teaching a more desirable profession, especially for people of color.”

Meyer said that while there are nationwide and statewide issues to be addressed, districts need to incentivize teachers by paying higher wages, create environments that are inclusive for teachers already in the district and have visible leaders of color.

“It’s not enough to just want to recruit people in,” Meyer said. “Retention is the other part of the problem.”

When Youngquist’s office led the change in how the Aurora district hires principals, the focus was to increase the quality of school leaders and remove bias that could allow a person to be invited into the process “just with a tap on the shoulder,” he said.

The new process requires a team of district leaders and other principals to observe candidates as they are asked to model practices through scenarios and demonstrations of situations they’re likely to confront as principals.

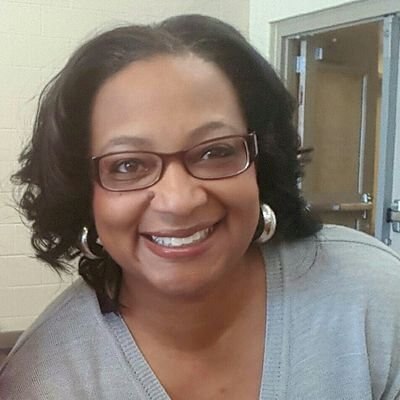

Yolanda Greer, principal of Aurora’s Vista Peak Exploratory was one of the first to go through that new hiring process three years ago.

“I will tell you at the end of it I certainly felt like I had been through a triathalon of some sorts,” Greer said. “But I do recall saying at every point, ‘I’m so impressed. I’m so appreciative that APS is taking the thoughtfulness that went behind creating this process to make sure we have leaders that are prepared.’ It made me want to be here even more.”

Speaking at a community meeting last month, Munn said the neighboring districts of Denver and Cherry Creek can offer more money, so Aurora must focus on other appeals to hire and retain diverse educators.

“We have to think about what’s the right atmosphere or what’s the right way that we can recruit or retain people in a way that makes them want to be part of what we’re doing here in APS,” Munn said. “Our ultimate winning advantage there is that we have a strong connection to the community. We also demonstrate to potential staff members that we are a district that has momentum. We are a district where there is opportunity. We are a district that can truly impact the community that we serve.”

Greer said she felt that draw to Aurora long before she applied for the principal position.

“I think because there was a public perception that Aurora was an underdog,” Greer said. “It’s a great opportunity to not only impact the school but the district and community.”

Though Aurora district officials are happy with how the principal process is playing out, they started working with a Virginia-based consultant last year to look at all hiring practices in the district. Munn said part of that work will include looking at whether the district is doing enough to increase diversity.

Like most school districts, Aurora has sent officials to recruit new educators from Historically Black Colleges and Hispanic Serving Institutions.

One thing that Greer said is in a district’s control is allowing a culture where issues of inequity can be discussed. In Aurora, she said she feels comfortable raising issues of student equity if she sees them.

For her, seeing other people of color in leadership positions in the district, including the superintendent, also made her feel welcome.

“In Aurora when I walk into leadership meetings, there’s a lot of people that look like me, so there’s that connectivity,” Greer said. “There’s open conversations and people listen.”

Earlier this year, Greer was reminded of the impact that leaders of color can have when her elementary students were asked to dress up for the job they hoped to have when they grew up.

Several of the students came to school dressed as their principal, Greer said.

“I want to make sure students of color can see someone that looks like them,” she said. “When they can see me in the specific role in education and they can say, ‘Wow, that can be something admirable and I want to aspire to that,’ it’s a big deal.”