Two years ago, Denver Public Schools approached its most affluent schools with an idea: What if, after enrolling all of the students who lived in their school boundaries, they prioritized filling their remaining open seats with low-income students from other neighborhoods?

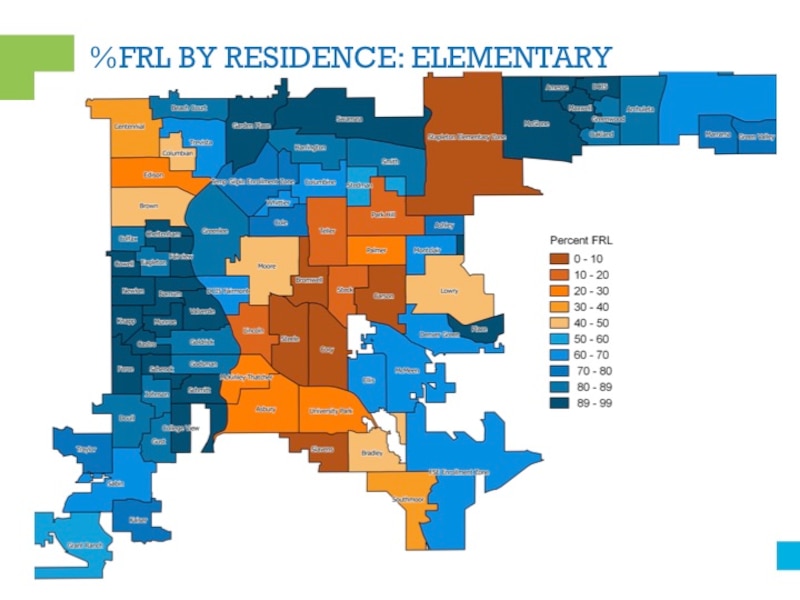

The goal was to increase socioeconomic integration in a gentrifying city where housing patterns have exacerbated a familiar problem: At some schools, very few students qualify for subsidized lunches. At other schools, nearly all do. And there aren’t enough schools in between, even though some research shows all students benefit when schools are integrated.

Six elementary schools with poverty rates far below the district average signed on to the idea. They were joined last year by Denver’s largest and most sought-after high school, East High, where hundreds of kids compete each year for freshman spots.

The results have been mixed. While the prioritization made little difference in diversifying the student population at some small elementary schools, it had a bigger effect at East, where every low-income eighth-grader who applied through Denver’s school choice system for a spot in this year’s freshman class was admitted, said Brian Eschbacher, the district’s executive director of planning and enrollment services. At smaller schools, a limited number of open seats and a lack of transportation to and from school hindered the results, he said.

The small-scale pilot program is one of the strategies being reviewed by the Strengthening Neighborhoods Initiative, a committee comprised of community leaders whose task is recommending policies to drive greater socioeconomic integration in the city’s schools.

Questions remain about the efficacy and equity of expanding the pilot. Among them, said the committee co-chairwoman, Diana Romero Campbell, is whether the responsibility to integrate Denver’s schools should fall solely on its low-income students — or whether more affluent students should share the burden of traveling outside their neighborhoods for the sake of integration.

“It really is, ‘What are the incentives that are needed?’ ” said Romero Campbell, who is president of Scholars Unlimited, a local nonprofit organization that runs after-school and summer learning programs. “If you make it a big mandate, does that disincentivize people and does it become busing all over again? The general consensus is that’s not what we want to do.”

In 1973, Denver Public Schools became the first school district outside the South ordered by the Supreme Court to desegregate through forced busing. By the time the district was freed from the order in 1995, tens of thousands of white students had left city schools for suburban and private ones. At the time, Denver Public Schools had about 64,000 students.

The district has tried over the past decade to attract students back, and enrollment has climbed precipitously, as has the city’s overall population. Today, Denver Public Schools educates about 92,000 students, three-quarters of whom are students of color and two-thirds of whom qualify for free or reduced-price lunch, a proxy for poverty.

Denver has universal school choice, which means that under a system that debuted in 2012, all students can use a single form to apply to any school in the district. That includes district-run schools and charter schools, which are publicly funded but privately run.

Some charters, such as the high-performing Denver School of Science and Technology, prize integration, and their enrollment rules have always reflected that goal. As the district opened more of its own schools and set up new “enrollment zones,” which are bigger boundaries that contain several schools, it followed suit, Eschbacher said. Certain schools have enrollment “floors” that require that at least half of their students qualify for subsidized lunches.

In some cases, the goal was to make sure a school’s population reflected the neighborhood population, he said. In others, it was to ensure families didn’t self-segregate within zones: all higher-income students at one school and none at the others, for example.

Then, two years ago, Eschbacher read a news story about school integration efforts in Brooklyn, N.Y. It inspired him to dash off a proposal to Superintendent Tom Boasberg that resulted in the district inviting schools where fewer than 40 percent of students qualified for free or reduced-price lunch to participate in a pilot prioritizing the enrollment of low-income students.

The schools’ boundaries wouldn’t change, Eschbacher explained, and they would still accept students who live within their boundaries first. But for the remaining open seats, they would give preference to low-income students who applied, boosting those students’ chances to attend one of the district’s more affluent schools, which also tend to be among its highest performing.

Asbury, Edison, Steele, Academia Ana Marie Sandoval and Creativity Challenge Community elementary schools opted in the first year, as did Slavens, which serves students in kindergarten through eighth grade. The following year, East High joined the pilot, as well.

Julia Shepherd, principal at Creativity Challenge Community, said her school opted in because integration has always been one of its goals. C3, as it’s called, opened in 2012 in a wealthier southeast Denver neighborhood as an all-choice, non-boundary school offering a curriculum that calls for collaborating with local museums and cultural institutions.

Its percentage of low-income students has historically been far below the district average. Last year, 9.5 percent of students qualified for free or reduced-price lunches. That number is up to 10.5 percent this year, but it’s 13.5 percent in kindergarten, which is the grade at which most new students enroll. Shepherd credits the increased diversity to the pilot program. Every low-income student who applied for a seat in C3’s kindergarten got in, she said.

“What we talk about so much here is community,” said Brent Applebaum, an assistant principal at C3. “…We want to be a representation of what Denver looks like.”

The pilot has been most successful at East, where historically about a third of all students have qualified for subsidized lunches. Of the 800 students in East’s freshmen class this year, 425 live in the boundary and 375 “choiced in,” Eschbacher said. The 375 includes 113 low-income students who live outside the boundary and don’t have a sibling at the school, which also gives applicants a priority. It also includes 170 non-low-income students who fit that description.

In the past, Eschbacher said, the 113 low-income students would have been tossed into a lottery with their non-low-income counterparts and faced a 50/50 chance of getting into the district’s most-requested school. Prioritizing them ensured they had a 100 percent chance, he said.

The numbers of low-income students who were accepted at each of the six elementary schools were so small that Eschbacher said he couldn’t disclose them for privacy reasons.

Part of the reason is that the factors that make the pilot work at East — lots of open seats and lots of demand — don’t exist at many other schools in the district, Eschbacher said. The seats at most more-affluent schools fill up with students who live in the boundary; Asbury had just five open kindergarten seats in 2016, according to district statistics, while Slavens had only six.

Full boundaries leave little room for choice students, low-income or not, Eschbacher said. “Are we giving them a boost no matter what?” he said. “Yep, we’re definitely trying. But one of the lessons we learned is that when few seats are available, it’s not going to move the needle very much.”

For enrollment prioritization to work, affluent schools must also attract enough interest from low-income students who want to choice in. That can be tough given that the district doesn’t provide transportation to most students who exercise choice. A recent district map of the percentage of low-income students in each elementary school boundary shows poor students are clustered in certain boundaries while wealthier students are clustered in others.

The Strengthening Neighborhoods Initiative has been meeting since June, and Romero Campbell, the co-chairwoman, said that all options are on the table as its initial work draws to a close. The committee has two more meetings scheduled and is expected to release its recommendations next month.