The Adams 14 school district is scaling back plans to create a track for students to follow to become biliterate, citing a need for students to learn English faster and a lack of qualified teachers.

Officials in the 7,500-student district in Denver’s north suburbs say they value biliteracy and will continue efforts to nurture it in early grades. But research casts doubt on the district’s new approach, and advocates worry that the changes will make teacher recruitment even more difficult.

Two years ago, under the previous superintendent, the Commerce City-based district had launched an ambitious kindergarten through 12th grade plan to prepare students to be literate in both Spanish and English.

The district struck a relationship with researchers at the University of Colorado Boulder to guide teachers on how to teach biliteracy in elementary schools. Now, Adams 14 is ending that relationship before the program has reached fourth and fifth grade classrooms district-wide, as originally envisioned. And the fate of biliteracy work in middle and high schools is uncertain.

New Adams 14 leaders say it’s not the district’s primary goal or responsibility to develop a student’s native language. The main goal, and where they see students being deficient, is in English fluency — which is why they want to get students immersed in English faster.

But research suggests that rushing to get students into English-only classrooms may hinder the long-term academic growth of students learning English as a second language. The implications are big in the Commerce City district, where about half of the students are learning English as a second language.

“The research is fairly conclusive,” said Kara Viesca, chair of bilingual education research for the American Educational Research Association. “We definitely know from research that students develop more dominant literacy skills in their native language making their literacy stronger — and those skills are transferable. If you know how to decode language in Spanish, you know how to decode language in English.”

But, she added, “One of the problems is it requires more patience.”

Adams 14, one of the state’s lowest performing districts, is on a short timeframe to show students are making academic improvements under a state-mandated plan.

The district’s turnaround work, approved by the state, included plans for the district to develop biliteracy options for students as well as plans to require all new teachers to get the education necessary to earn state endorsements in cultural and linguistically diverse education.

“These efforts are intended to build capacity to continue and grow the biliteracy program and to assure that the needs of our culturally and linguistically diverse student population are being met by recruiting the most highly-qualified and talented individuals,” the turnaround plan states.

Although some work to train and recruit more skilled teachers is continuing, the number of teachers in Adams 14 that hold such a qualification remains low, in part because of a high turnover.

Expanding programs requires qualified teachers, but those teachers won’t come to the district if leaders aren’t committing to the biliteracy models and the original plan to expand them, advocates say.

Under the original plan, the biliteracy framework would roll out in the elementary schools under the guidance of the CU researchers.

The plan called for three options at the middle and high school level, including a biliteracy track for students who had been in the biliteracy classrooms in elementary school, and two other options for students who want Spanish instruction but are new to it. Students taking biliteracy programs from elementary through high school would be able to earn a Seal of Biliteracy proving they are fluent in English and another language.

Adams 14 was one of three districts in Colorado to lead the way in offering the seal for high school graduates. But the district’s work creating the path from kindergarten through 12th grade to prepare students to be biliterate was the part being watched as a potential model for other districts.

“We had pointed to Adams 14 as one of the state leaders in recognizing biliteracy and recognizing that it doesn’t just happen with people talking to their kids in Spanish,” said Jorge Garcia, executive director of the Colorado Association for Bilingual Education. “It really takes work. We were extremely hopeful that the community would get a good, solid, research-based program and instruction that would really have long-term benefits.”

While officials say they will keep the biliteracy classrooms that already exist through third grade, they said they might make a school-by-school decision on whether to continue expanding the model to fourth and fifth graders if there is interest and if there are qualified teachers.

And Superintendent Javier Abrego said the district is “ready to fly on our own,” without the help of the university researchers that are training teachers to run the bilingual classes.

At the middle and high school level, officials are also hesitating to say those biliteracy options will expand as originally envisioned, saying they have to look more closely at data to gauge its effectiveness.

District officials added that some of the responsibility to help students be bilingual should be on parents.

“Spanish is my first language, but I didn’t have the opportunity of being in a Spanish classroom,” said Aracelia Burgos, chief academic and innovation officer. “I maintained my Spanish because my parents made sure that I did. I want to empower our parents to do the same.”

It’s a sensitive issue for some people in the community, as they say it brings back memories of the district’s history mistreating Hispanic students and families and banning Spanish in schools. In 2014, the federal government published findings from an investigation, saying the district was violating civil rights policies through its English-only policies, creating a hostile environment for Spanish-speaking students, families and teachers.

Colorado Association of Bilingual Educators officials say they started hearing similar concerns resurface at the start of this school year — including from teachers feeling pressure to not spend as much time instructing students in Spanish, and from families concerned that their children were no longer getting homework in a language they could help them with.

Maria Trujillo, a mom of a 6-year-old in Dupont Elementary’s biliteracy classrooms, said she was not aware the district was considering changes to the biliteracy program, which she thinks is working well for her son. She said she was looking forward to him staying in the program until at least fifth grade.

“He’s learning both languages very well,” Trujillo said. “In fact, he already understands more English than I do. I think it only benefits students to be able to become bilingual.”

As concerns about the fate of the biliteracy efforts mounted, parents, educators and advocates started packing school board meetings to voice support for the programs.

Days later, as the superintendent published a statement reiterating a commitment to bilingual education and biliteracy — in kindergarten through third grade — the district suspended Edilberto Cano, its director of English language development. He oversaw the district’s biliteracy work, the partnership with the university and the training of teachers.

District officials won’t comment on why Cano was put on administrative leave.

Rep. Dominick Moreno, a Democrat representing Commerce City, and graduate of the district, joined supporters of biliteracy in speaking to the board at a meeting last week.

“Gone are the days when speaking more than one language was a liability. Now it’s an asset,” Moreno said. “I certainly hope that you’ll carefully consider some of the changes and just make sure that all of our kids, that their multilingual abilities are understood and respected.”

Researchers and advocates say that despite conclusive and extensive research on the benefits of bilingual instruction, the programs continue to face challenges across the country by critics who often hold values that contradict the research.

“If the value is to have a bilingual kid perform as if they are English monolingual, the bilingual education research is not going to support that,” said Viesca, of the American Educational Research Association.

Another researcher, Kate Menken, who is professor of linguistics at Queens College in New York, said she gets so many calls every year from people asking if there is research on bilingual programs that she created a page on her website just to direct callers to multiple studies. One big question she doesn’t answer, she said, is around the time needed to become biliterate.

“There’s a lot of focus on speed, and trying to speed up the process, but these programs are not really about that,” Menken said. “It’s about giving students time to learn and learn well.”

District officials say they are not so confident in research, pointing to their own data from the first group of students that were in the biliteracy classrooms. Those students (this year they are third graders) are showing some growth, but they are behind students in the district’s traditional English classrooms, the district says.

Pat Almeida, the principal of Dupont Elementary, and CU Boulder researchers said those students are likely showing different outcomes because they started the biliteracy learning at first grade, not kindergarten, and because they were the first to go through the program as teachers were still learning how to run those classrooms.

According to a report completed by the CU Boulder researchers working with the district to roll out the biliteracy program, students who have come after that first group of students, including those now in kindergarten, first grade and second grade, are testing better than students who are in English classrooms.

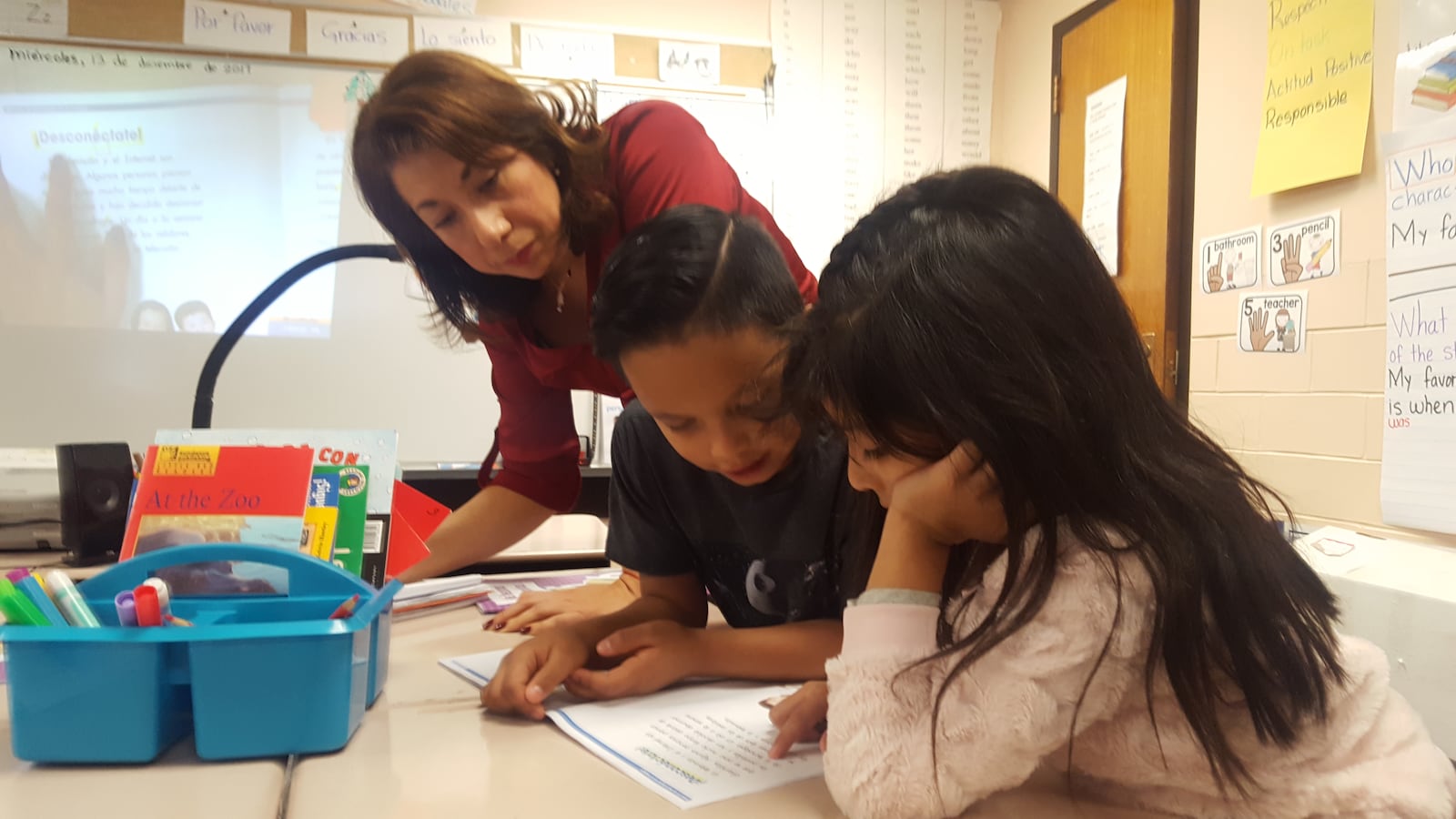

In biliteracy classrooms, teachers instruct literacy in Spanish for at least one hour each day. There is also a period of literacy instruction in English, and teachers may use a mix of languages for the rest of the day to teach other subjects.

At Dupont Elementary, a classroom of kindergarteners last week spent their hour of Spanish literacy time sharing and discussing how to define technology and electricity.

Then, as all kids sat on the rug at the front of their class, teacher Mary Fernandez took out a large copy of a Spanish kids book about technology, and before reading, asked the students to guess if the book was fiction or nonfiction and to explain why.

The Dupont biliteracy teachers are highly qualified teachers with state endorsements, said Abrego, the superintendent. Their qualifications are necessary to making the biliteracy program work, he said.

The district is pressing forward with other efforts aimed at English language learners. Under an agreement with the BUENO Center for Multicultural Education at CU Boulder, Adams 14 pays a third of the course fees for district teachers to earn that state endorsement that qualifies them to teach students who don’t speak English. It’s called the Culturally and Linguistically Diverse endorsement.

It takes about two years of college courses to complete the endorsement. As part of the partnership, classes are offered in district schools in the evening. This year there are nearly 30 teachers taking the college classes, although a handful of the teachers are joining from other school districts.

For teachers who don’t have the endorsement, the district provides training in the district’s approaches to incorporating English language development in traditional classrooms. So far, 200 of the district’s 458 teachers have been trained in those approaches. But because the district is low on the number of coaches, once teachers take the district classes, most don’t have help throughout the year to apply the strategies.

Although getting help paying the courses is an incentive for teachers, once they complete their endorsement, Adams 14 doesn’t give them a bonus or a raise. Burgos, the chief academic officer, wants to find a way to offer sign-on bonuses next year.

Because teachers with those qualifications are in short supply, they’re also in high demand. This year, 56 of the district’s 458 teachers have the state endorsement. That’s comparable to numbers in nearby districts and statewide, with 5,493 of the state’s 53,567 teachers having an endorsement.

Adams 14 schools have had high turnover, although it decreased from 2014 to 2016-17. Last year, the district also had more than 48 percent turnover in their instructional staff, which includes teacher coaches, higher than any other metro area district.

Prior to being placed on leave, Adams 14’s English language director, Cano, was also working to create a faster condensed program for an internal endorsement that the district could require to make sure all district teachers are qualified to teach English learners.

Aurora Public Schools last year created a similar internal endorsement based on 96 hours of online and face-to-face professional learning. In its second year, Aurora now has 1,199 of the district’s 2,313 licensed staff — more than half — with either the state or district endorsement.

Of the teachers running the biliteracy classrooms in Adams 14, only half of them had the state endorsement last year. CU Boulder researchers working with the district say while it would be good to have more, not expanding the biliteracy work will only make teachers more scarce.

“There is a shortage of bilingual teachers,” said Kathy Escamilla, director of the BUENO Center at CU Boulder. “But you are not going to expand a program if you’ve created hostility. You have to have some initiative to recruit and retain these teachers.”