The old way of teaching science would have had Denver science teacher Melissa Campanella giving a lecture on particle collisions, then handing her students a lab that felt a bit like following a recipe from a cookbook.

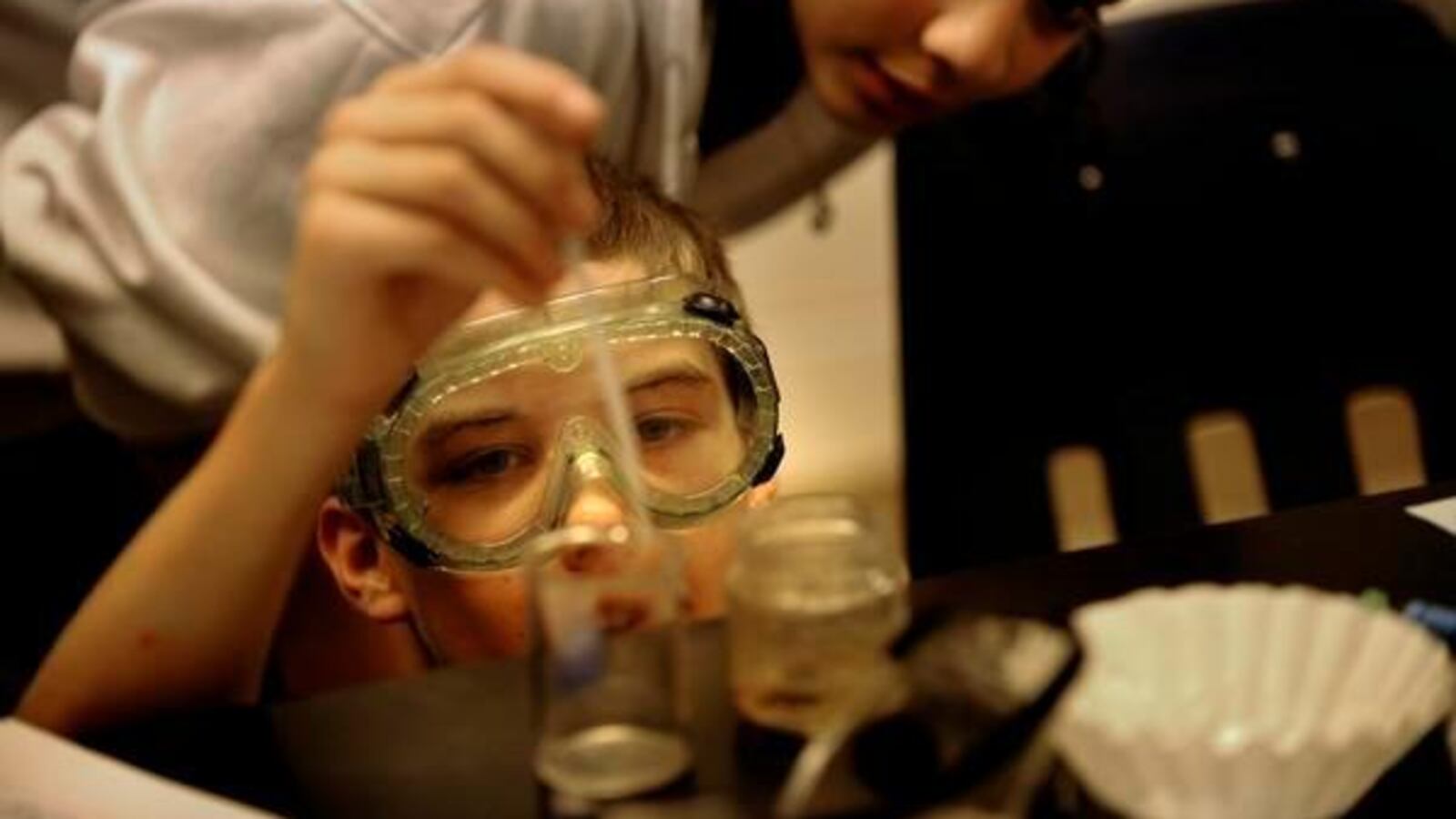

Now she starts the same lesson by activating glow sticks, one in hot water, the other in cold. Her students at Noel Community Arts School make observations, brainstorm what might cause the differences they detect, come up with models and visual diagrams that map those ideas, share those models with each other, revise, read about the collision model of reactions, and revise again.

“Before, they would maybe know basic ideas from memorization, and maybe they would retain this information long enough for me to give a quiz on it,” Campanella said. “Now they have a better understanding of why those fundamental rules exist, and because they drew those conclusions themselves, they remember it better.”

This is the future of science education as envisioned by the scientists and educators who developed the Next Generation Science Standards. A committee working to revise Colorado’s science standards has recommended we adopt a modified version of them. Because Colorado has local control, individual school districts will still be responsible for their own curriculum, but the standards will lay out what students are expected to know at each grade level.

These science standards are part of the same sweeping philosophical shift in how we teach that brought us the Common Core math and reading standards, and provoke some of the same tension about what’s more important: knowing a thing or knowing how we know it? At the same time, the website promoting the Next Generation standards takes great care to say these are not part of the Common Core standards, which have become heavily politicized and are often seen as an example of federal overreach.

Colorado’s State Board of Education, the science standards review committee, and the state’s science teachers will have to navigate this terrain between now and this summer, when the new standards need to be finalized — and then for years to come as they’re implemented in Colorado classrooms.

Changing how kids learn, and perhaps what they learn

Next Generation standards, or ones closely modeled on them, have been adopted in 38 states, many of whom were also involved in developing this new approach. These standards and lessons based on them are already being used in some classrooms in at least 12 Colorado school districts, including Adams 12, Denver Public Schools, and Boulder Valley School District.

The standards are based on the 2011 Framework for K-12 Science Education published by the National Research Council, a document that is itself based on some two decades of research on how children learn science.

Supporters of Next Generation standards believe that the ability to use scientific methods of inquiry is more important than memorizing facts and leads to a much deeper understanding of the material. Opponents include cultural and religious conservatives who object to references to evolution, climate change, and the age of the earth, as well as people who fear children won’t learn basic knowledge about science – the steps of photosynthesis, Newton’s Laws of Motion, the parts of a plant or of the human body.

“In the end, they just didn’t come out with the right balance,” said Mike Petrilli, president of the Fordham Institute, a conservative-leaning education think tank. “They emphasized practice in a way that ends up crowding out the content knowledge.”

The Fordham Institute’s reviewers gave the Next Generation Science Standards a C. For some perspective, they gave the existing science standards of 26 states, including Colorado, a D or lower. However, they think there are much better examples out there, including the previous standards of states like Massachusetts that have since adopted Next Generation-based standards.

What about the “aha” moments that teachers like Campanella report from the classroom when they use these new methods?

“It’s not surprising that fantastic teachers can take these standards and do that,” Petrilli said. “The question is: In classrooms around the country, can teachers take these standards and get the appropriate nudge to teach the content?”

Defenders of the new standards are blunt: In a world where we can look up the entire accumulated knowledge of the human race on our phones, no, it isn’t actually that important to memorize a lot of facts. But that isn’t the same as not knowing scientific content.

David Evans, executive director of the National Science Teachers Association, which was heavily involved in developing the standards, said that representatives of every speciality thought not enough of their content was included – and they were right, he added. The creators of the standards wanted students who would be prepared to understand the world, even if specific ideas change over time as scientific understanding progresses.

Evans lists off the things that were considered “science” when he went to school: the parts of the plant, the elements and their position on the periodic table, balancing equations in chemistry. Many of these things remain true. But as any adult who’s had to get up to speed on all the newly discovered dinosaurs knows, the content of science changes — and about a lot more than just the apatosaurus.

“When I went to school, I learned that all life on Earth derives from the energy of the sun. Photosynthesis, everything comes from there,” Evans said. “That turns out not to be true. We have life on Earth driven by chemistry discovered in volcanic vents in the depths of the ocean. So it turns out that not all life derives from the energy of the sun, and it might – might – turn out to be the case that there is more chemosynthetic life on earth than life that derives from the energy of the sun.”

The way the Next Generation Science Standards are organized has also sparked some concerns. The ideas are grouped in a three-dimensional way, with science practices and skills, core ideas, and cross-cutting concepts for every expectation. An example at the middle school level is that students should be able to “develop a model that predicts and describes changes in particle motion, temperature, and state of a pure substance when thermal energy is added or removed.” The science practice is developing a model to explain phenomena, the core idea is that gases and liquids are made of molecules or inert atoms that are moving about relative to each other, and the cross-cutting concept is that cause and effect can be used to make predictions.

Critics say this is confusing, and supporters admit it takes some practice to learn how to read them. They also require teachers to change how they do their job, which requires training and support.

“If someone were to just look at the standards statement, they would have to pause and think, what does this really mean I would be teaching and want my students to learn?” said Kris Kilibarda, state program consultant for the Iowa Department of Education. “But I would argue we want that.”

Some states that have adopted Next Generation-based standards have had major campaigns to train teachers, while others have far fewer resources. Teachers are going online to share the lessons they’ve developed with each other, and in state after state, officials said the wealth of resources being developed and shared, often for free or little cost, in the wake of Next Generation adoption, has been a huge help. California also released some 1,000 pages of implementation documents that other states can use.

Nationwide, most of the controversy around Next Generation standards hasn’t been about the finer points of pedagogy but about the chronically divisive issues of climate change, evolution, and even the age of the earth. In Kansas, Citizens for Objective Public Education sued the state unsuccessfully on the claim that the standards’ “non-theistic worldview” amounted to an establishment of religion. In New Mexico, state education officials restored references to global warming and evolution after there was a backlash to the backlash.

Idaho, meanwhile, is in the final stage of approval – for the third time. The standards committee has taken new public testimony and adopted new language around each of the touchy topics. Scott Cook, director of academics for the Idaho State Department of Education, said the standards’ focus on scientific method and inquiry give educators a way to maintain scientific rigor, even as references to climate change and the age of the earth are stripped out.

Students can still learn how to construct a timetable for the age of the earth using rock strata, even if the standard doesn’t include “4.6 billion years,” he said.

“If they’re analyzing that data accurately, whatever number they come up with is going to be a pretty darn big one,” Cook said. “This idea of inquiry is a good one for having people not feel like it’s indoctrination.”

A big change for Colorado

Colorado is in the middle of a six-year review of its academic standards, and the proposed changes in science are more substantial than those in most other subject areas.

“The biggest thing that parents and teachers will notice is that it really asks students to do more with science, to engage and understand the concepts at a deeper level,” said Joanna Bruno, science content specialist with the Colorado Department of Education. “Science is moving away from being a noun, something you learn, to being a verb. Science is not static, and in the past, that’s how it’s been taught.”

Some topics also will move to different grade levels, but Colorado students will still need to know the same material to graduate as they do now.

The committee working on Colorado’s standards made a number of revisions to the Next Generation standards: editing for clarity, distinguishing more between grade levels, reorganizing how the standards are presented, and putting expectations in the form of a question. For example: “How do the properties and movements of water shape Earth’s surface and affect its systems?”

Colorado’s biggest deviation from the Next Generation standards won’t be a change at all here: There won’t be engineering standards. Many rural schools simply wouldn’t have the capacity to add it, Bruno said.

When a draft version of the standards was presented to the State Board of Education earlier this month, many of the questions revolved around implementation, especially in rural school districts. Democratic members of the board, who represent a majority, said they like the direction that science standards are moving.

But Steve Durham, one of the most conservative members of the board, defended the value of rote memorization, objected to the inclusion of climate change, and questioned whether an education based on Next Generation standards will prepare graduates to pursue careers in science and technology, which he sees as the purpose of science education “for legislators and for taxpayers.”

Charlie Warren, a teacher licensure officer at the University of Northern Colorado and a member of the standards review committee, responded that that was just one purpose. The broader goal is to educate scientifically literate and engaged citizens, he said.

Hinting at the fight to come, Durham countered: “You want a scientifically literate citizen that accepts without question your little statement on page 121 here about climate change.”

Durham thinks students won’t understand basic science principles if they don’t have to memorize them, but Campanella, the high school teacher, said her experience is that students understand these principles at a much deeper level when she teaches following the guidance of Next Generation standards – and they make science accessible for students who might have thought these subjects weren’t for them.

“Our kids deserve to be held to really high expectations, and these standards make sure that happens,” she said. “I expect you to be able to do some science and not just regurgitate someone else’s science.”