Maren Jorgensen has taught special education in Denver Public Schools for eight years. Next school year she’ll be teaching in Minnesota, earning $22,000 more doing the same job.

Aurora kindergarten teacher Shannon Rizzo is also moving out of state. She and her fiance currently rent a room in a friend’s house. When they started looking for their own place, they realized they couldn’t afford anything in the Denver metro area – but could enjoy a comfortable standard of living if they moved to her fiance’s native Texas.

Meanwhile, out on Colorado’s Eastern Plains, Superintendent Tom Slattery of the 781-student Burlington district makes cold calls to math majors from small colleges in Kansas and Nebraska, looking for potential teachers among people who never before imagined themselves in the classroom.

“You may hear ‘hard-to-fill positions’, and people bring up math and science,” Slattery said, “But I am telling you, every position is hard to fill in Burlington.”

A package of bills making their way to the desk of Gov. John Hickenlooper aims to make those positions a little easier to fill, but the legislative effort will have only a modest impact on Colorado’s teacher shortage because it fails to tackle the root causes. Teacher pay is below the national average, dramatically so in rural districts, experienced teachers have plenty of other options, and fewer people are entering a profession that promises long hours for low pay and little respect.

Addressing the shortage of teachers in certain subject areas and throughout rural parts of Colorado was one of the top education priorities this session. The 2018-19 budget sets aside $10 million to reduce teacher shortages, and the bills check off many of the recommendations in a report commissioned last year.

The proposals provide financial assistance to student teachers and teachers pursuing alternative certification in exchange for commitments to remain with their districts, expand residency programs to see if more intense support systems help more teachers stay in the field, and extend grants to school districts and charter schools to come up with their own incentive packages. Several hundred young teachers are likely to benefit directly.

But lawmakers avoided more expensive recommendations, like loan forgiveness and a minimum salary for teachers. They also declined to take up more politically charged ideas, like loosening licensure requirements or re-examining the state’s accountability system for teachers.

“We know that there are strategies that work and there are proven models that are a good investment,” said Leslie Colwell of the Colorado Children’s Campaign. “We feel like it’s unfortunate that some of them were not seriously considered, particularly the loan forgiveness.”

Republicans on the Senate Finance Committee killed a bill that would have provided up to $5,000 a year in loan forgiveness for five years for educators in hard-to-fill positions and regions where the teacher shortage is more acute. The discussion became a debate about licensure, which many Republicans see as unnecessary regulation. GOP lawmakers asked why educators need higher degrees that cause them to incur student loan debt in the first place.

Over in the Democratic-controlled House, a bill that would have allowed districts to hire unlicensed teachers faced almost certain death until its Republican sponsor completely reworked it into a much more modest proposal helping out-of-state teachers more easily obtain a Colorado license.

The teachers union, a powerful interest at the Capitol, strongly opposes efforts to further erode licensure. Colorado already has roughly two dozen “alternative pathways,” training other than traditional university educator-preparation programs, often for teachers who are already in the classroom with temporary credentials.

Doing away with licensure doesn’t seem to be a magic bullet. Many charter schools hire unlicensed teachers but still have a hard time filling certain positions. Slattery, in Burlington, has an exemption from licensing requirements so he can cast his hiring net far and wide, and he’s found some great teachers that way. But it’s still a painstaking process to find candidates, and each one needs to be trained at the district’s expense.

“The funding of public schools needs to change,” Slattery said. “Some people don’t like to hear that. I grew up in rural Colorado, and I’m probably one of the most conservative superintendents you’ll meet. We either have to decide education for our young kids is a priority and No. 1, or it’s not.”

Colorado lawmakers are sending more money to schools this year, including an extra $30 million for rural schools. State Rep. Brittany Pettersen, the Lakewood Democrat who chairs the House Education Committee, said she hopes that money translates to higher pay for teachers.

And she believes the teacher shortage bills, several of which she sponsored, will have a meaningful impact.

“We did what we could with the dollars that were set aside,” she said. “We’ll see an impact because of these bills, but to make a big impact, we need a lot more money.”

Last year’s report stopped short of recommending a minimum salary for teachers, an idea that appeared in an early draft, and didn’t put a dollar amount on what it would take to make a meaningful dent in persistent shortages in some areas. That disappointed some rural districts that hoped that quantifying the problem would force the legislature to act.

Right now, the state even doesn’t have a solid grasp on the scope of the problem. A voluntary survey of school districts found that a large majority had seen a decrease in qualified applicants. Eighty-one percent of urban and suburban districts started the 2017-18 school year with unfilled positions, as did almost two-thirds of rural districts. Statewide, the reported vacancies only numbered in the hundreds, out of a teacher workforce of some 52,000, but most rural districts didn’t respond to the survey.

Starting this fall, the survey will be mandatory, giving the state education department a clearer picture of where and in what fields the need is most acute. State Rep. Jim Wilson, a Salida Republican and former superintendent, said even small numbers of vacancies can be a big problem. A vacancy of one is a teacher shortage, he said, if it means a high school has no math teacher.

A study found that in 95 percent of the state’s rural districts, teacher salaries fall below the cost of living. Colorado recruits 50 percent of its teachers from out of state, so we’re more vulnerable to losing teachers to higher-paying jobs elsewhere. Within Colorado, rural districts struggle to compete with urban Front Range districts.

Stephanie Aragon, who studies these issues for the Education Commission of the States, said many places use incentives to lure teachers to hard-to-serve areas, but those programs often are not sustainable. Once teachers get experience and fulfill whatever service obligation they incurred, they depart for greener pastures.

This has led some in Colorado to focus on a “grow your own” approach. Three bills this session use elements of this strategy, which involves helping students from communities that have a hard time hiring enough teachers become teachers themselves in their hometowns or nearby. Research supports this approach, and rural districts like the idea of recruiting teachers from among their own.

One bill would provide a $10,000 fellowship to student teachers in rural communities, and another provides stipends up to $6,000 for educators in rural districts pursuing alternative licensure or additional education. A third allows student teachers to have their own classrooms and earn a salary and tuition reimbursement, with the state offsetting some of the cost. Each of these programs would require the beneficiaries to stay with that district for a set amount of time.

The hope is that these programs will also diversify the teacher workforce by providing support that could be critical to students from low-income families.

Another bill provides money to expand and monitor teacher residency programs, which support and mentor teachers early in their careers. The goal here is keep more young teachers in the classroom beyond the five-year mark.

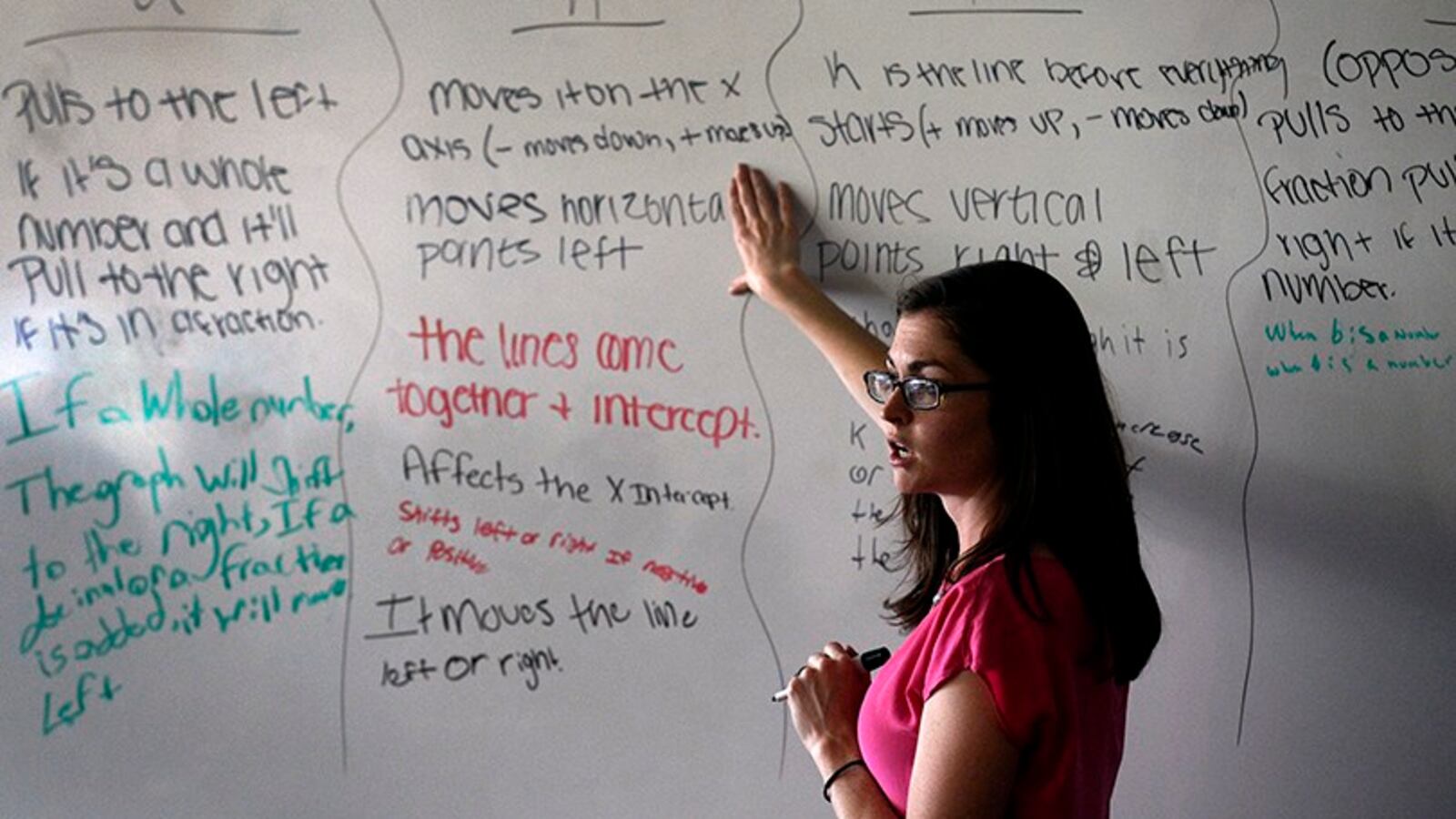

Tory Tripp, a ninth-grade math teacher at Manual High School in Denver, says her residency program was essential to getting her through her first year of teaching.

“The opportunity to be in a classroom for the entire year and understand the ups and downs of the school year and having practice leading things on my own was really important,” she said. “If I need to vent or need advice, I still call my friends from the my residency program.”

Even so, her first year was “brutal” and not everyone from her residency group remained a teacher.

Tripp said that when she’s thought about leaving teaching, it’s been the stress that has tipped her over the edge, not the money. Nonetheless, higher pay for teachers who take on challenging jobs would help.

“If we really want to pull teachers to those schools, something needs to be different between a school in Cherry Creek and a school like Manual,” she said, distinguishing the more affluent suburban district from her own school. “You need to compensate for the greater demands that working in a high-needs school place on you.”

Kerrie Dallman, president of the Colorado Education Association, the state’s largest teachers union, said improving pay is essential, but she also noted the need to boost respect for teachers and improve working conditions. Yet there were no policy recommendations to address that – and no bills either.

“The respect component is key because it acknowledges that educators are professionals, and we should listen to them when they raise concerns about student learning conditions and teacher working conditions,” she said.

Dallman ties this issue specifically to Colorado’s law linking teacher evaluations to students’ performance on state assessments. Nationally, a quarter of teachers who leave the profession list dissatisfaction with teacher accountability and evaluation measures as a major reason; roughly twice as many as cite low pay. The state report did not recommend revisiting Colorado’s teacher effectiveness law, and the idea didn’t come up at the legislature this year. However, some Democratic gubernatorial candidates have said it’s time.

Mary Hulac, who teaches language arts at Prairie Heights Middle School in the Greeley-Evans district north of Denver, a school that faced state intervention last year, said the hardest thing about teaching is “the lack of positive feedback,” not knowing for years if you’ve made a difference. She’d like to see the state put some resources into promoting “how attractive teaching is, for the intangibles.”

“I tell my students every day, this is the best job,” she said.

Hulac also thinks training for principals isn’t given enough attention, compared to training for teachers. More than a fifth of teachers who leave the profession cite dissatisfaction with school leadership.

“As I’ve gotten older, I gravitate toward the strongest principals, and I would put up with more hassle and paperwork to have strong leadership,” she said.

A bill that would have provided leadership training for principals died in the Senate State Affairs committee near the end of the session.

Read more about the teacher shortage bills passed by the Colorado General Assembly.