The Denver school district is not serving Native American students well. Fewer than one in four Native American sixth-graders were reading and writing on grade-level last year, according to state tests, and the high school graduation rate was just 48 percent.

Even though that percentage is lower than for black or Latino students, educator Terri Bissonette said it often feels as if no one is paying attention.

“Nobody says anything out loud,” said Bissonette, a member of the Gnoozhekaaning Anishinaabe tribe who graduated from Denver Public Schools and has worked in education for 20 years as a teacher and consultant. “We’re always listed as ‘others.’”

Bissonette aims to change that by opening a charter school called the American Indian Academy of Denver. The plan is to start in fall 2019 with 120 students in sixth, seventh, and eighth grades and then expand into high school one grade at a time. Any interested student will be able to enroll, no matter their racial or ethnic background.

The Denver school board unanimously and enthusiastically approved the charter last week – which is notable given enrollment growth is slowing districtwide and some board members have expressed concerns about approving too many new schools.

But the American Indian Academy of Denver would be unlike any other school in the city. The curriculum would focus on science, technology, engineering, art, and math – or STEAM, as it’s known – and lessons would be taught through an indigenous lens.

Bissonette gives a poignant example. In sixth grade, state academic standards dictate students learn how European explorers came to North America.

“When you’re learning that unit, you’re on the boat,” Bissonette said. “I’d take that unit and I’d flip it. You’d be on the beach, and those boats would be coming.”

Antonio Garcia loves that example. The 17-year-old cites it when talking about why the school would be transformational for Native American youth, a population that has historically been forced – sometimes violently – to assimilate into white culture. For decades, Native American children were sent to boarding schools where their hair was cut and their languages forbidden.

Garcia is a member of the Jicarilla Apache, Diné, Mexikah, and Maya people. A senior at Denver’s East High School, he recalls elementary school classmates asking if he lived in a teepee and teachers singling him out to share the indigenous perspective on that day’s lesson.

“Indigenous students don’t have a place in Denver Public Schools,” Garcia said. “We’re underrepresented. And when we are represented, it’s through tokenism.”

According to the official student count, 592 of Denver’s nearly 93,000 students this year are Native American. That’s less than 1 percent, although Bissonette suspects the number is actually higher because some families don’t tick the box for fear of being stigmatized or because they identify as both Native American and another race.

The district does provide extra support for Native American students. Four full-time and three part-time staff members coordinate mentorships, cultural events, college campus visits, and other services, according to district officials. In addition, five Denver schools are designated as Native American “focus schools.” The focus schools are meant to centralize the enrollment of Native American students, in part so they feel less isolated, officials said.

But it isn’t working that way. While the number of students at some of the schools is slightly higher than average, there isn’t a large concentration at any one of them. Supporters of the American Indian Academy of Denver hope the charter will serve that role.

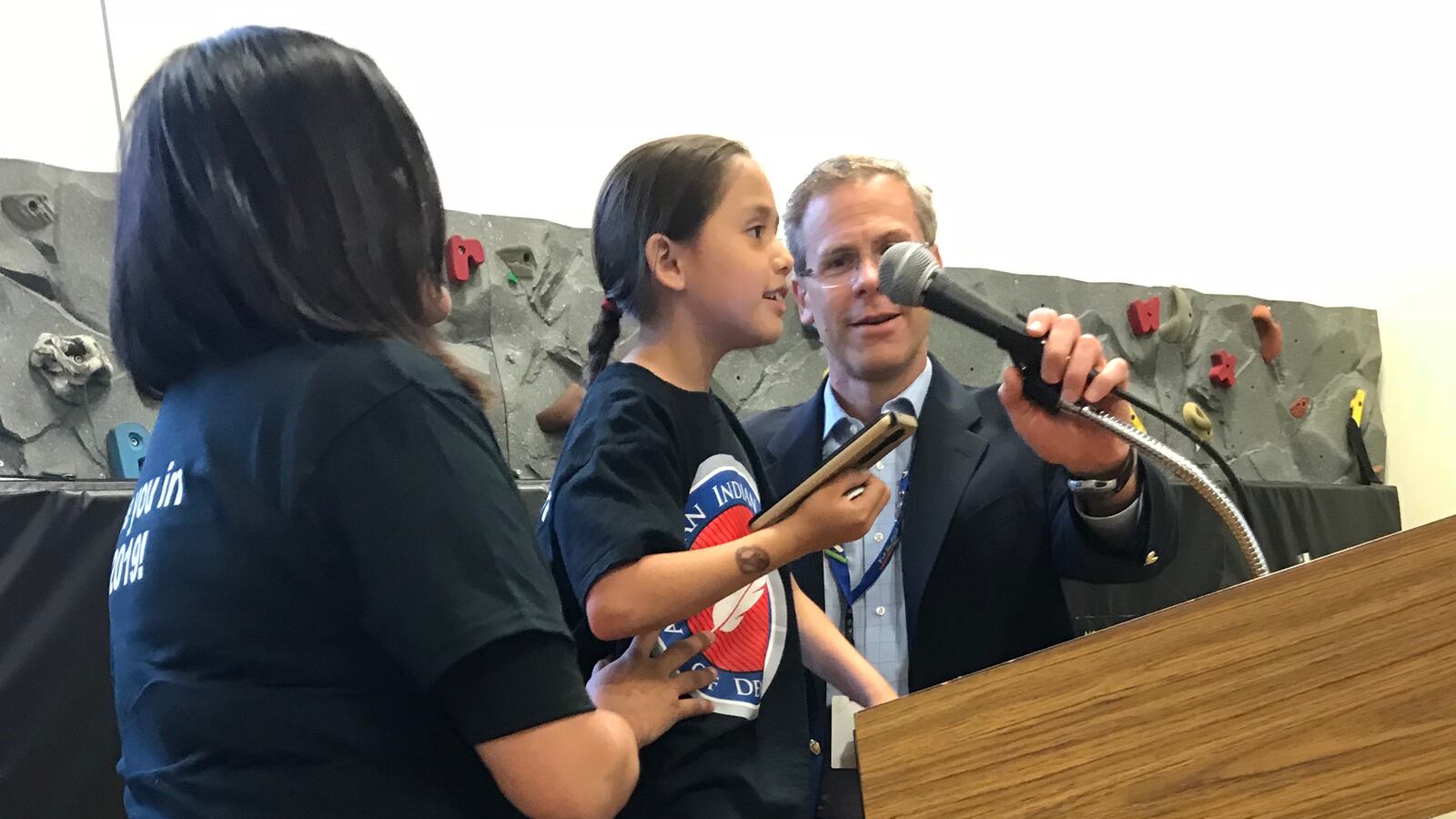

“It’s very hard being the only Native person that my friends know,” second-grader Vivian Sheely told the school board last week. “It would be nice to see other families that look like my own.”

That sense of belonging is what Shannon Subryan wants for her children, too. Subryan and her daughters are members of the Navajo and Lakota tribes. Her 7-year-old, Cheyenne, has struggled to find a school that works for her. Because Cheyenne is quiet in class, Subryan said teachers have repeatedly suggested she be tested for learning disabilities.

“Our children are taught that listening before speaking is more valued than speaking right away,” Subryan said. “She understands everything. It’s just a cultural thing.”

After switching schools three times, Cheyenne ended up at a Denver elementary with a teacher who shares her Native American and Latina heritage. She’s thrived there, but Subryan worries what will happen when Cheyenne gets a new teacher next year. As soon as Cheyenne is old enough, Subryan plans to enroll her at the American Indian Academy of Denver.

In addition to the school’s “indigenized” curriculum, Bissonette envisions inviting elders into the classrooms to share stories and act as academic tutors, exposing students to traditional sports and games, and teaching them Native American languages. Above all, she said the school will work to hire high-quality teachers, whether they’re Native American or not.

The school is partly modeled on a successful charter school in New Mexico called the Native American Community Academy. Opened in 2006, it has a dual focus on academic rigor and student wellness. Last year, 71 percent of its graduates immediately enrolled in college, school officials said. In Denver, only 38 percent of Native American graduates immediately enrolled.

Several years ago, the New Mexico school launched a fellowship program for educators who want to open their own schools focused on better serving Native American students. Bissonette will be the first Colorado educator to be a fellow when she starts this year.

She and her founding board of directors are hoping to open the American Indian Academy of Denver in a private facility somewhere in southwest Denver. That region is home to the Denver Indian Center and has historically had a larger population of Native American families.

However, she said she and her board members realize the Native American population isn’t big enough to support a school alone. More than half of all Denver students are Latino, and they expect the school’s demographics to reflect that. Many Latino students also identify as indigenous, and Bissonette is confident they’ll be attracted to the model.

“This really is a school from us, about us,” she said.