With less than a month to go before the primary, the Democratic candidates for governor of Colorado are sparring not over the future of education policy but over the past.

Two main issues are at play in the negative ads, contentious debate exchanges, and accusatory mailers that have made their way into mailboxes across Colorado: the state’s teacher effectiveness law, authored by one of the candidates and slammed by those supporting another, and the meaning of an op-ed yet another candidate penned some 15 years ago.

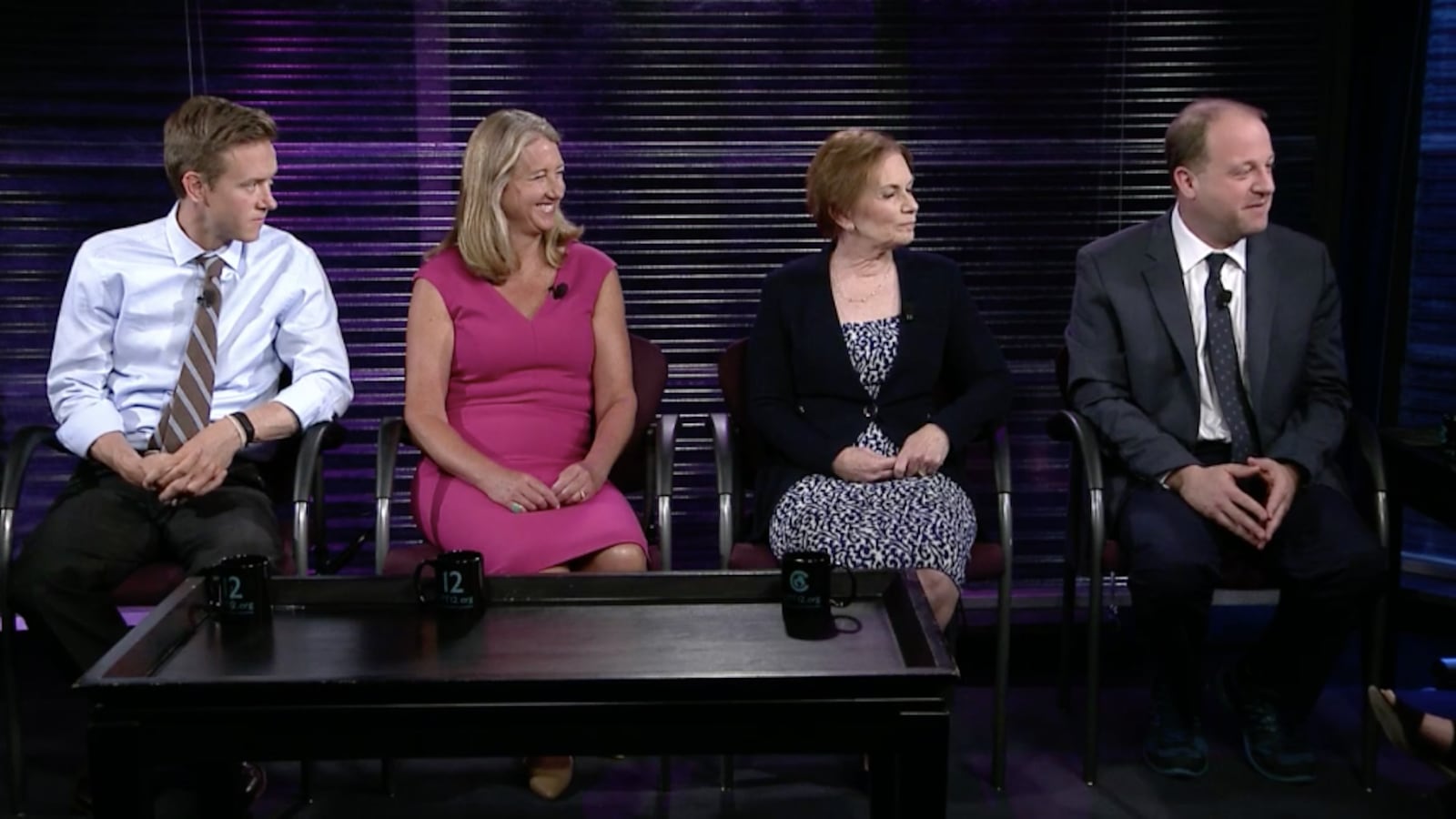

The Democrats vying for the nomination are former state Sen. Mike Johnston, former state Treasurer Cary Kennedy, Colorado Lt. Governor Donna Lynne, and U.S. Rep. Jared Polis.

Teachers for Kennedy, a union-backed independent political group, launched the first negative TV ad targeting Johnston and Polis and followed it up with mailers critical of Polis. In two televised debates, Johnston and Polis decried the ad and accused Kennedy of once supporting the very policies for which her supporters are going after them. There are now two ads in circulation targeting Kennedy, one from Polis’s campaign and another from the independent expenditure committee supporting him; both ads accuse Kennedy of violating the candidates’ pledge to avoid negative campaigning. Only Lynne — whose track record includes helping to found Colorado Succeeds, a business-oriented education reform group — has yet to be targeted in ads and mailers.

As Chalkbeat looked into the claims at issue in a race where policy differences between Democratic candidates are relatively small, we repeatedly found ourselves asking people to recall the tenor and tone of conversations dating back six, 10, even 15 years.

Back then, the state’s education policy landscape looked a whole lot different. Certain reform policies once considered within the mainstream on the Democratic side are now widely associated with the Republican Party, and particularly with U.S. Secretary of Education Betsy DeVos. That’s one reason the campaigns are reaching into the past.

Colorado’s primary is June 26. Here are the claims and counterclaims you’re likely to hear between now and then.

At Issue: The Teacher Effectiveness Law

CLAIM: A television ad from Teachers for Kennedy describes Johnston as pushing a “conservative anti-teacher bill.” In a debate, Kennedy said that bill “introduced high stakes testing” in Colorado.

FACT CHECK: Johnston wrote Colorado’s teacher effectiveness law, which ties teacher evaluations to student performance on standardized tests, and strips tenure protections from teachers who repeatedly earn low ratings. This bill was passed by a Democratic-controlled legislature and signed by a Democratic governor. Many states adopted similar legislation in response to urging from Democratic President Barack Obama.

Standardized tests that are used to judge the performance of schools existed in Colorado well before the teacher effectiveness law. Without changing that law, Colorado has already reduced the amount of time students spend taking standardized tests.

CLAIM: Johnston said in a Colorado Public Television debate that Kennedy authored a 2012 report praising that very legislation, Senate Bill 10-191.

FACT CHECK: Kennedy was the co-chair of the Colorado School Finance Partnership, a 2012 initiative of the Colorado Children’s Campaign. One premise of the partnership’s recommendations was that increased funding should be tied to measurable improvements in the education offered to Colorado children.

The final report described the teacher effectiveness law as part of “a system that provides the necessary accountability and data tools to drive student achievement and provide meaningful targets for improvement.” One recommendation called for full funding of the teacher evaluation system, set forth in the law, along with money for training to help teachers improve performance.

Kennedy said that not every member of the group agreed with the report in its entirety. However, the report itself describes a “full-consensus model” in which all parties had to agree to every recommendation.

Other committee members recalled exhaustive conversations about the proposals in the report, but said at times there was agreement on abstract principles, but not on every last detail.

One member, Tim Taylor, then with Colorado Succeeds, a business-oriented bipartisan education reform group, recalled that the teacher effectiveness law was treated as a settled matter. “There was this feeling that we were all together and moving in the right direction,” he said. “I don’t remember anyone having a major problem with anything.”

The representative from the Colorado Education Association, which opposed the law, also signed off on the final report.

Kennedy’s campaign did not provide evidence that she publicly opposed the teacher effectiveness law when it was being debated at the legislature, nor has Johnston offered more concrete evidence that she actively supported it. Kennedy was state treasurer at the time, and a campaign spokeswoman said she didn’t often weigh in on issues outside of that role.

WHY ARE WE TALKING ABOUT THIS? The teacher effectiveness law is one of the few clear areas of policy difference between Kennedy and Johnston. Many teachers dislike this law and feel it doesn’t reflect the full scope of what they do in the classroom. Kennedy, who has the endorsement of the teachers unions, has pledged to revisit the law if elected governor. Linking the law to a culture of testing, as Kennedy does, expands the message beyond teachers and intra-party disputes. Colorado was a national center of the so-called “opt-out” movement, in which parents excused their children from taking state assessments; that movement included people from across the political spectrum.

At Issue: Support for Vouchers

CLAIM: Polis supports voucher programs that would allow public money to be used to pay private school tuition. This claim has been made in television ads, mailers (here and here), and Kennedy campaign press releases.

FACT CHECK: In Congress, Polis has consistently voted against voucher programs. Polis was on the State Board of Education in 2003, when Colorado’s legislature was debating a voucher proposal that had divided Democrats. Press accounts at the time describe Polis as supporting the measure. In an op-ed, he defended the “modest voucher proposal” and the Democrats who supported it, including then-state Attorney General Ken Salazar. Polis now describes the op-ed as written primarily to stop the “vilification” of Salazar, who has endorsed Kennedy in the governor’s race.

“Salazar is right – this experiment deserves a fair test, an honest chance,” Polis wrote at the time. “If it succeeds, it will benefit the lives of children and families. If it fails, at least we can bring closure to a toxic debate that has divided us for too long.”

That voucher bill passed but was overturned by the Colorado Supreme Court on grounds that it violated local control because it took money away from school districts. A school district-initiated voucher program in Douglas County later became the subject of years-long litigation, before a new, union-backed school board voted to end it.

The mailers use a “four years ago” time reference from a 2007 Denver Post article to make Polis’s op-ed appear much more recent than it is.

CLAIM: Kennedy worked for an organization that lobbied for vouchers. Polis has said this in two televised debates.

FACT CHECK: Kennedy went to work for the Colorado Children’s Campaign in April 2003, shortly after the voucher bill passed the legislature. The Children’s Campaign’s decision to back the voucher bill — provided it was targeted at students from low-income families in poor-performing schools — was controversial within the organization.

Barbara O’Brien, who headed up the organization at the time (and now serves on the Denver Public Schools board), said Kennedy’s focus was on school finance. As the vouchers bill made its way to governor’s desk and subsequently wended its way through the courts, the issue came up during senior team meetings in which Kennedy took part, O’Brien said, and she cannot recall Kennedy ever expressing opposition on the matter.

“She didn’t work on it, but she knew what our priorities were,” O’Brien said.

Kennedy’s campaign reiterated that Kennedy has always opposed vouchers. The campaign also objected to using anecdotal evidence of non-opposition to vouchers in the context of her involvement of the Colorado Children’s Campaign.

WHY ARE WE TALKING ABOUT THIS? Vouchers are unpopular with Democratic voters, particularly primary voters, and especially now, when vouchers are closely linked with an unpopular Republican president and his education secretary. In the beginning of the primary season, Polis was seen as the presumptive front-runner, in large part due to his ability to self-fund his campaign, so Kennedy and her supporters have had reason to focus on him.

Asked directly about whether they would support district-level vouchers during a 9 News debate, Polis and Lynne said that would be a matter of local control over which the governor has limited authority. Polis said he would ensure that no public money went to religious schools. Johnston and Kennedy both said explicitly that they oppose vouchers at any level of government.

The voucher discussion starts around 15:25.

At Issue: Ads from Independent Groups

CLAIM: It would be illegal for Cary Kennedy to call on Teachers for Kennedy, an independent political group, to stop running ads that attack the records of Johnston and Polis. In the 9 News debate, Johnston said Kennedy should tell the group to stop running negative ads and reject the group’s endorsement if they don’t comply. Kennedy responded that doing so would be a violation of campaign finance law and amount to “silencing teachers.”

FACT CHECK: Colorado law prohibits coordination between candidates or political parties and what are known as independent expenditure committees, the state equivalent of PACs. Examples of coordination would be a candidate telling an independent political group what to say or how to spend money, or using the same political consultant without some sort of firewall.

However, expressing an opinion wouldn’t constitute coordination.

“Clearly coordination is illegal,” Lynn Bartels, a spokeswoman for the Colorado Secretary of State’s Office, told Chalkbeat in an email, “but our election officials tell me there is nothing illegal after an ad has appeared about offering an opinion.”

In the debates, Kennedy said she doesn’t like negative campaigning or “sensationalizing” issues, but has refused to renounce the ad, saying it conveys educators’ perspectives to voters.

It’s worth noting that the ads do not make mention of Lynne. This may reflect Teachers for Kennedy’s view that the current lieutenant governor doesn’t pose much of a threat to their preferred candidate. Lynne, who was a healthcare executive before being tapped to be current Gov. John Hickenlooper’s No. 2, doesn’t have a large political base of her own and has struggled to raise money in a race with record spending. For her part, Lynne has called herself “the adult in the room,” and said voters aren’t interested in this “bickering.”

WHY ARE WE TALKING ABOUT THIS? Johnston and Polis say that Kennedy’s willingness to reap the benefits of negative ads while insisting she’s adhering to the Clean Campaign Pledge represents a failure of leadership. Johnston based a fundraising email off the attack, and Polis now has his own ad featuring teachers criticizing Kennedy for going negative; Kennedy’s campaign has characterized Polis’ ad as negative in its own right.

This week, Polis sent a letter to the state Democratic Party, saying that if Kennedy doesn’t adhere to the Clean Campaign Pledge against negative campaigning, he wouldn’t either.

Expect three more weeks of this.