Denver students who return this fall to the five small schools on the Montbello campus will find a refurbished library with a dedicated librarian — something they didn’t have this past year.

New stadium lights will mean high school athletes no longer have their after-school practices cut short by the setting sun. Students at the two high schools on the campus will be able to take elective courses at either school, widening their academic possibilities.

These changes will create something closer to a traditional high school experience for students in far northeast Denver. Some residents have been asking for the return of a comprehensive high school in the region. It hasn’t had one since the school board voted in 2010 to close low-performing Montbello High and replace it with smaller schools that share facilities.

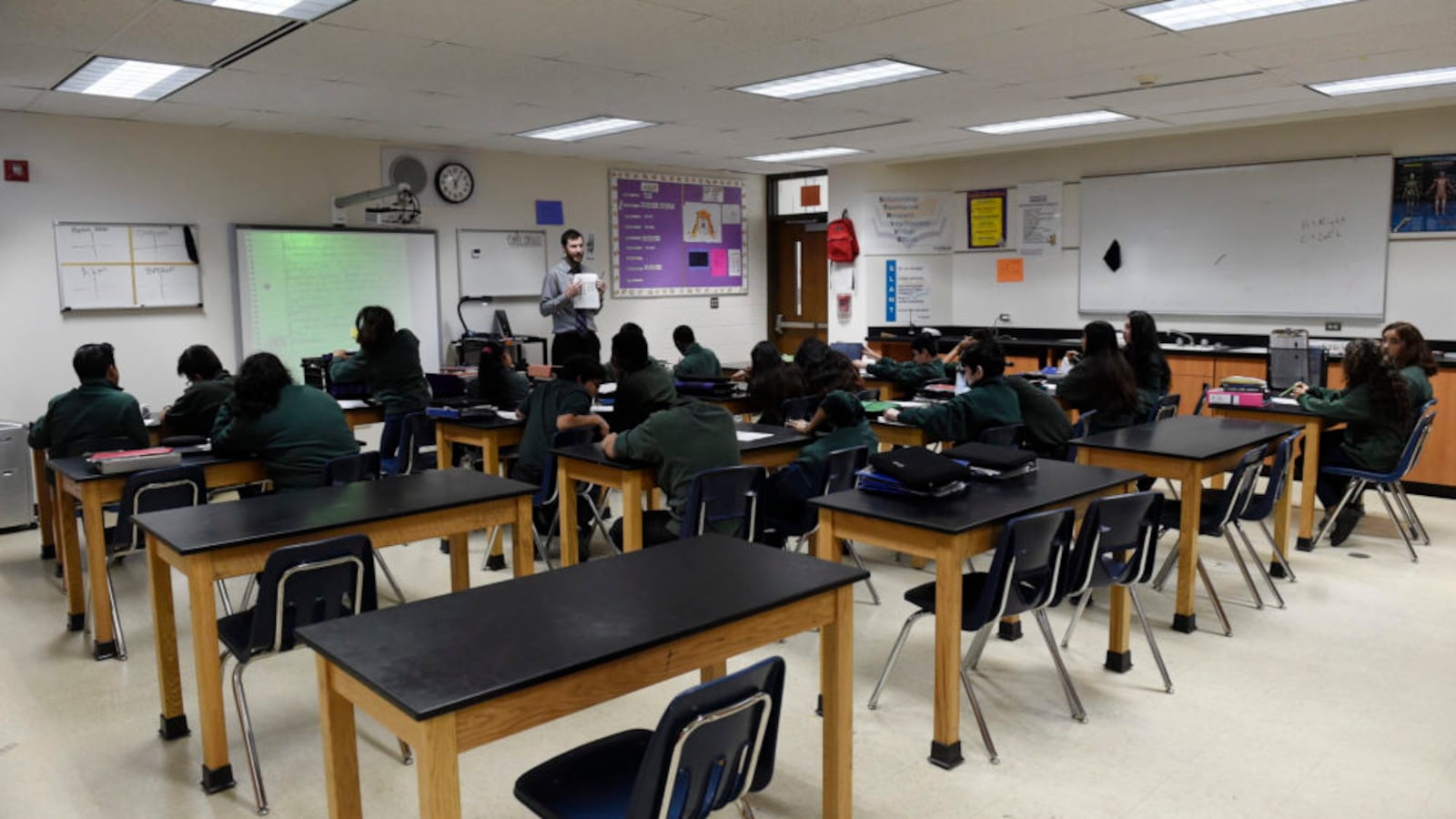

The three middle and two high schools on the Montbello campus served nearly 1,800 students this past school year. Nearly all of them were students of color, and 88 percent of students qualified for free or reduced-price lunch, an indicator of poverty.

District officials point to higher test scores and rising graduation rates as proof the small schools are working. But some community members disagree, in part because they say shared campus arrangements have created other academic and social inequities. In the past year, parents, athletic coaches, and students have been increasingly vocal in demanding change.

Denver Public Schools Superintendent Tom Boasberg said the district heard the feedback “loud and clear.” The library renovation and other changes will “bring some real, tangible, and meaningful benefits to our students in the far northeast,” he said.

Community members said they’re a start.

“We like to say we acknowledge what the DPS has done in response to all of this community agitation,” said Brandon Pryor, a Denver parent and football coach who has emerged as one of the strongest advocates for change. “We want to stay away from thanking them because the things they’re doing are the things they should have been doing already.”

School board member Jennifer Bacon, who represents the area, wants to help the community continue its advocacy. She is working to form a committee of parents, students, teachers, and other residents to come up with a vision for what public education should look like in the far northeast — and, perhaps, a model for future new schools in the region.

“You can’t just dangle low-hanging fruit and believe that’s enough,” Bacon said of the district’s efforts to address the concerns. However, she added, “you have to also start somewhere. The fact that we are means that a point was made, and it was received.”

The changes the district is making for the 2018-19 school year stop well short of reopening a traditional high school. Superintendent Boasberg said that while he hears that desire, “our first priority is to invest in the schools that we have.”

The changes include:

Providing “open access to a high-functioning library” for the schools on the Montbello campus, “including a dedicated librarian, for research and study time,” according to a letter Boasberg sent to families after touring the campus alongside community advocates.

All five schools will share a single library and librarian.

This past school year, one of the schools on the campus, DCIS Montbello, used the library as a math classroom during the fall semester, district officials said. When the library reopened during the spring semester, there was no librarian and no computers there. (Students have access to computers in their classrooms, and some schools issue students their own, officials said.)

The library renovation will add technology, and update the paint, flooring, furniture, and book selection, district officials said. It will be funded through a variety of sources, including a tax increase voters approved in 2016. Funding for the librarian position will come out of the district’s central budget, not individual school budgets, officials said.

Adding lights to the athletic fields at the Montbello campus and the nearby Evie Dennis campus, which houses a mix of elementary, middle, and high schools. The district is also aligning bell schedules at all district-run high schools in the far northeast.

That will enable student athletes from the various schools who play as a single team under the banner of the Far Northeast Warriors to start practice earlier. Football coach Tony Lindsay said that this past year, the schools’ bell schedules were all over the place. The school with the earliest dismissal time let students out at 2:45 p.m.; the latest dismissed them at 4:15 p.m.

A bus went from school to school, collecting the athletes, who wouldn’t arrive at the field until 4:45 p.m., he said. That posed a major problem in the fall, when it gets dark by 5:15 p.m.

The district is paying for the lights at the Evie Dennis campus with money from the 2016 tax increase and using reserve funds to pay for the Montbello lights, officials said.

Hiring an athletic liaison to help students meet the academic eligibility requirements to play sports for Denver Public Schools and qualify for college scholarships.

When Lindsay coached football at a traditional high school in south Denver, he required his players to attend a 45-minute study hall before practice so they could keep up with their homework. But the disparate bell schedules and lack of field lights didn’t allow him to do the same in the far northeast. As a result, he said, some athletes fell behind. Others left for larger, more traditional high schools in other parts of Denver and in surrounding districts.

“They didn’t want this mess,” Lindsay said. “I don’t blame them, but I’m hurt by it. I live out there. That’s my community.”

The liaison will connect student athletes with tutoring and other academic support, officials said. The position will be funded by the district, not the schools.

Expanding the number of available electives for some students. High school students at DCIS Montbello and Noel Community Arts School will be able to take elective courses at either school. According to district officials, those could include Advanced Placement, college-level, and foreign language courses, as well as band, orchestra, dance, and theater.

Many of the changes for next year are related to athletics. That’s because some of the strongest advocacy has come from the football coaches and their players, who showed up at school board meetings this year to speak publicly about the needs in the far northeast.

Lindsay, Pryor and others also participated in a series of community meetings run by Denver Public Schools over the past year and a half. The meetings started as an effort to ask residents in the region what they want in their schools. They ended in a heated debate about whether to reopen a traditional high school. The idea prompted backlash from leaders of the small schools that replaced Montbello High, as they initially saw it as a threat to their existence.

That conflict seems to have cooled, but those who want a traditional high school aren’t relenting. Narcy Jackson, who also participated in the meetings and runs a mentoring program for student athletes, said the changes the district is making don’t go far enough to address inequities.

“They give, like, a crumb,” Jackson said. “That’s supposed to suffice.”

District officials argue that students in the far northeast are getting a better education now than they did before the phase-out of Montbello High, which began in 2011 and ended in 2014 when the last class graduated. In addition to the two small high schools on the Montbello campus, there are six other small high schools and three alternative high schools in the region. They are a mix of district-run and charter schools, and all but one have fewer than 600 students.

Average ACT scores in the far northeast increased from 15.7 points out of 36 in 2011 to 17.7 in 2016, district data shows. That number does not include scores from the alternative schools.

The five-year graduation rate rose from 69 percent to nearly 88 percent. The district prefers to use a five-year graduation rate, rather than a four-year rate, because officials believe in allowing students to stay longer to take free college courses or do apprenticeships.

In addition, high school enrollment in far northeast schools has nearly doubled, from 2,056 students in 2010 to 4,069 students in 2017, district data shows. Officials see that as a sign families are increasingly satisfied with their local schools.

Pryor, the parent and football coach, sees things differently. Test scores are increasing, but he said they’re still not where they should be. ACT scores lag behind the district average. At DCIS Montbello, only 11 percent of 9th graders met expectations on last year’s state literacy test. As for the graduation rate, “that’s not an indication of kids doing better,” Pryor said.

“They’re just passing them through,” he said, “creating an illusion that they’re serving our kids better, but they’re not.”

He’d like to work with other community members to design a brand-new high school. He hopes to start by visiting schools around the country that have been successful in educating black and Latino students. He said he appreciates that Bacon, the school board member, wants to keep the conversation going beyond the changes the district is making next year.

“We’ve identified problems,” Pryor said. Now, he added, “it’s time to work on solutions.”