All three school Colorado districts under the gun to improve their academics showed some gains on test results released Thursday — but the numbers may not be enough to save one, Adams 14, from facing increased state intervention.

Of the three districts, only the Commerce City-based Adams 14 faces a fall deadline to bump up its state ratings. If the district doesn’t move up on the five-step scale, the state could close schools, merge Adams 14 with a higher-performing neighbor, or order other shake-ups.

The school district of Westminster and the Aguilar school district, also on state-ordered improvement plans, have until 2019 to boost their state ratings.

The ratings, expected in a few weeks, are compiled largely from the scores released Thursday which are based on spring tests.

District officials in Adams 14 celebrated gains at some individual schools, but as a district, achievement remained mostly dismal.

“We continue to see a positive trend in both English language arts and math, but we still have work to do,” said Jamie Ball, manager of accountability and assessment for Adams 14.

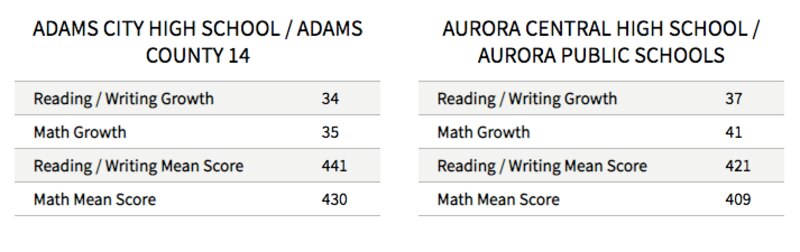

The district’s high school, Adams City High School, which has its own state order to improve its ratings by this fall, posted some declines in student achievement.

District officials said they are digging into their data in anticipation of another hearing before the State Board of Education soon.

In a turn likely to invite higher scrutiny, district schools that have been working with an outside firm, Beyond Textbooks, showed larger declines in student progress.

In part, Ball said that was because Beyond Textbooks wasn’t fully up and running until last school year’s second semester. Still, the district renewed its contract with the Arizona-based firm and expanded it to include more schools.

“Its a learning curve,” said Superintendent Javier Abrego. “People have to get comfortable and familiar with it.”

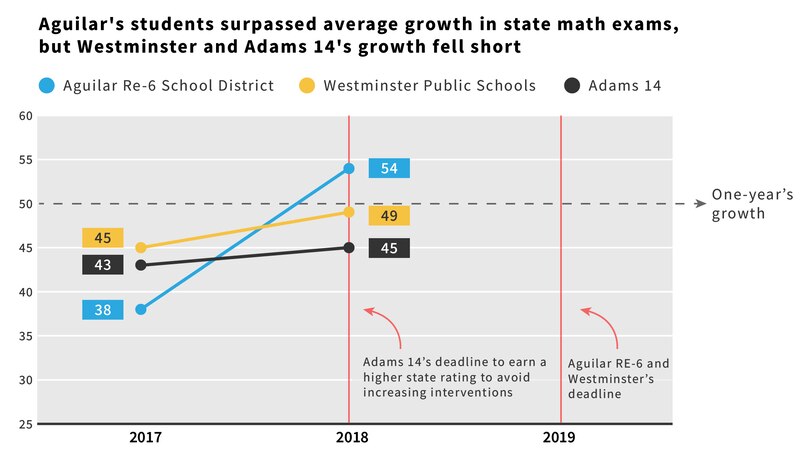

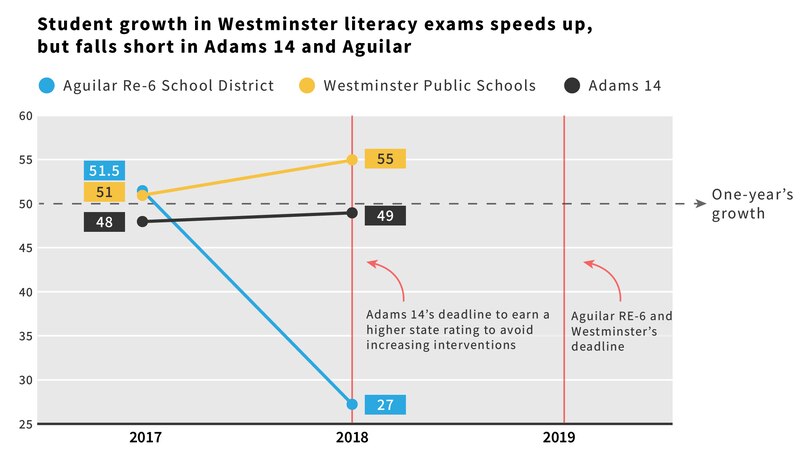

For state ratings of districts and high schools, about 40 percent will be based on the district’s growth scores — that’s a state measurement of how much students improved year-over-year, when compared with students with a similar test history. A score of 50 is generally considered an average year’s growth. Schools and districts with many struggling students must post high growth scores for them to get students to grade level.

In the case of Adams 14, although growth scores rose in both math and English, the district failed to reach the average of 50.

Westminster district officials, meanwhile, said that while they often criticize the state’s accountability system, this year they were excited to look at their test data and look forward to seeing their coming ratings.

The district has long committed to a model called competency-based education, despite modest gains in achievement. The model does away with grade levels. Students progress through classes based on when they can prove they learned the content, rather than moving up each year. District officials have often said the state’s method of testing students doesn’t recognize the district’s leaning model.

“It’s clear to us 2017-18 was a successful year,” said Superintendent Pam Swanson. “This is the third year we have had upward progress. We believe competency-based education is working.”

The district posted gains in most tests and categories — although the scores show the extent of its challenge. Fewer than one in five — 19.6 percent of its third graders — met or exceeded expectations in literacy exams, up from 15.9 percent last year.

Students in Westminster also made strong improvements in literacy as the district posted a growth score of 55, surpassing the state average.

Westminster officials also highlighted gains for particular groups of students. Gaps in growth among students are narrowing.

One significant gap that narrowed in Westminster was between students who qualify for free or reduced-price lunch, a common measure of poverty, and those who don’t. In the math tests given to elementary and middle school students, the difference in growth scores between the two groups narrowed to three points from 10 points the year before, with scores hovering around 50.

Results in individual schools that are on state plans for improvement were more mixed. Three schools in Pueblo, for instance, all saw decreases in literacy growth, but increases in math. One middle school in Greeley, Prairie Heights Middle School, had significant gains in literacy growth.

The Aurora school district managed to get off the state’s watchlist last year, but one of its high schools is already on a state plan for improvement. Aurora Central High School has until 2019 to earn a higher state rating or face further state interventions.

Aurora Central High’s math gains on the SAT test exceeded last year’s, but improvement on the SAT’s literacy slowed. The school’s growth scores in both subjects still remain well below 50.

Look up high school test results here.