After fourth-graders at Aurora’s Peoria Elementary read “Tiger Rising” as a group last week, several excitedly shot up their hands to explain the connections they had made.

“It’s not just a wood carving, it represents their relationship,” one student said about an object in the book. Others talked about another symbol, the lead character’s suitcase, while one student wondered about the meaning of the story’s title.

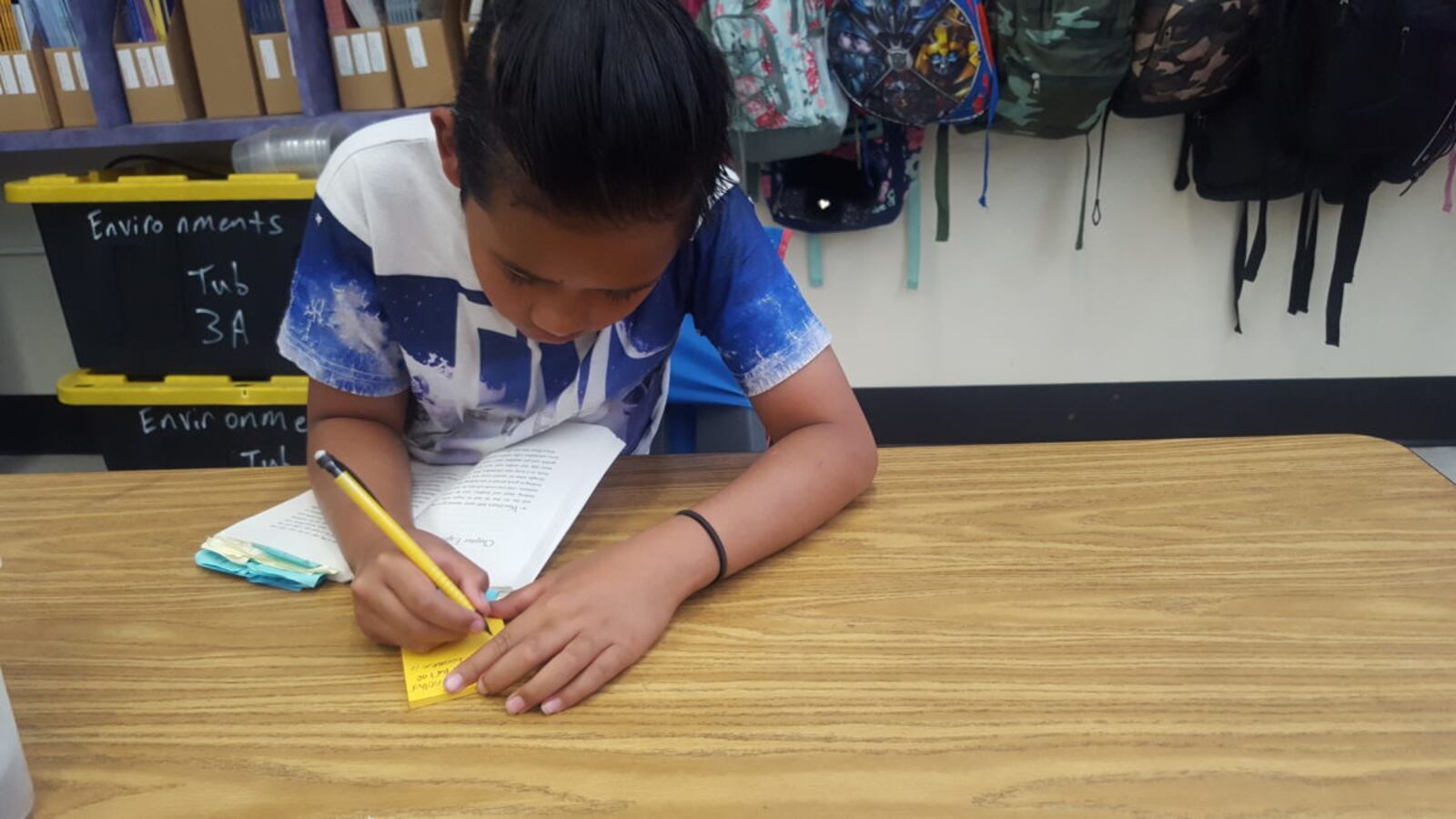

Nick Larson’s class rushed back to their desks, excited about what they had learned and ready to look for symbols in their own books during independent reading time. As they read, students filled their books, including the “Lost Treasure of the Emerald Eye,” “Because of Winn-Dixie” and “Super Sasquatch Showdown,” with sticky notes about what they were noticing in the text.

It’s one small way Aurora teachers are integrating writing and reading, a practice officials refer to as “balanced literacy.” It means reading about writing, and writing about reading. It’s not a new teaching practice, but the district has spent $4.7 million on new literacy curriculum from two different sources — schools get to pick one — to help teachers combine those lessons.

The materials replace curriculum adopted in 2000.

At Peoria, a school of about 429 students, of which approximately 90 percent qualify for free or reduced-price lunch, an indicator of poverty, teachers were using some of the new curriculum last year. Larson, who also coaches other teachers half of the day, said he pushes students to think about what the author might have wanted them to feel. He asks students to write about the characters in the books they read, to better understand them.

“We’re trying to make connections throughout the day,” Larson said.

The previous literacy materials called for teaching reading and writing separately, and some didn’t include writing. They also no longer aligned with standards that the state changed in 2010.

An internal Aurora audit found different schools using a wide variety of resources as they supplemented the out-of-date curriculum.

And this fall, district staff found another reason why the new curriculum was necessary.

In dissecting state test results, Aurora discovered that about 40 percent of its third-through-eighth-graders earned zero points on certain writing sections of the test.

“We’ve got to address that,” said Andre Wright, Aurora’s chief academic officer. “You can’t leave that level of opportunity on the table. We just can’t do that.”

Starla Pearson, the district’s executive director of curriculum and instruction, explained that she expects to see changes soon.

“With the literacy curriculum that is in place right now, I have great confidence,” Pearson said. “We did not have something that specific, looking at writing instruction.” All of the curriculum now, she said, does include writing resources.

“This gives me such encouragement on the one hand because it’s a pretty simple fix … you’re seeing a real clear path to increasing points,” said Debbie Gerkin, an Aurora school board member. “The discouraging part is why wasn’t this happening?”

But about three-quarters of Aurora schools were already using the writing half of the curriculum before this year. Now all elementary and middle schools will use both the reading and writing parts of the district’s newly adopted curriculum. The district is now reviewing potential changes to high school curriculum.

District officials told the board that it’s possible the change in state tests in 2015 may have also contributed to the low scores. Previously, students took separate reading and writing tests and earned separate scores. The new state tests ask students to read a passage, and then respond to it in writing, combining the subjects.

Aurora officials said they didn’t have a way to compare the results they found with other districts. Colorado and most districts do not have comparable detailed results on segments of the state tests.

Wright said this information has prompted him to ask many questions internally. For starters, Aurora will focus training for teachers on combining reading and writing lessons. The district has spent $180,000 to provide teacher training on using the new resources.

But Bruce Wilcox, the president of the Aurora teachers union, said that teachers have been concerned about the limited time they had to learn and explore the new materials, which were only provided to them a few weeks before classes started.

Pearson said early anecdotal feedback has been positive.

“Teachers are saying, ‘thank you, we have a resource,’” she said.

Larson, who was one of 36 teachers from 10 schools who got to review and recommend which curriculum the district should adopt, said he likes several aspects of the materials.

“I feel like I’m being pushed as a teacher,” Larson said.

The district plans to survey teachers about the materials, and will look at internal test data throughout the year, as well as writing results next year to look for improvements.

“We will see a difference,” Pearson said.