Daily math instruction. An additional hour of math review two times a week. Chess games during snack breaks, and four more hours of math on Saturdays for those who are still struggling.

All that focus is part of what helped students at Vega Collegiate Academy, a charter school in northwest Aurora, earn the highest math growth score in the state. That means the individual students at Vega on average made the most progress year-over-year compared with their academic peers. The previous year, a Denver charter school had the highest growth.

Vega also earned the state’s fourth-highest growth scores on literacy tests. And the school was just in its first year of existence.

“We know what works, it’s just hard to do,” said Kathryn Mullins, the school’s founder and executive director. “Some people just don’t want to do it.”

Vega opened last year with 96 students in kindergarten and fifth grade. This year, it’s added two more grade levels. It’s operating in a wing of a Lutheran church, and nearly all of the students qualify for free and reduced-price lunches, a common measure of poverty.

Mullins said all students came in at least a year behind grade level, and said most students caught up to grade level by the end of the year. On state tests, results show 46.9 percent of Vega students met or exceeded expectations for math, and 30.6 percent did in literacy — that’s higher than Aurora district results, in which 16.7 percent of students met or exceeded expectations for math, and 25.6 percent did so for literacy.

In the case of math, Vega’s results are also better than the state’s. Although Vega opened in 2017, the state measures growth of students by comparing their scores with those they earned the previous year, even if they were at different schools.

Vega students have an extended school day that runs until 5 p.m. — yes, students were tired the first few weeks of school, Mullins said, but she indicated that they get used to it. They do get daily recess, and this year the school started a flag football team and several other after-school programs based on student interests.

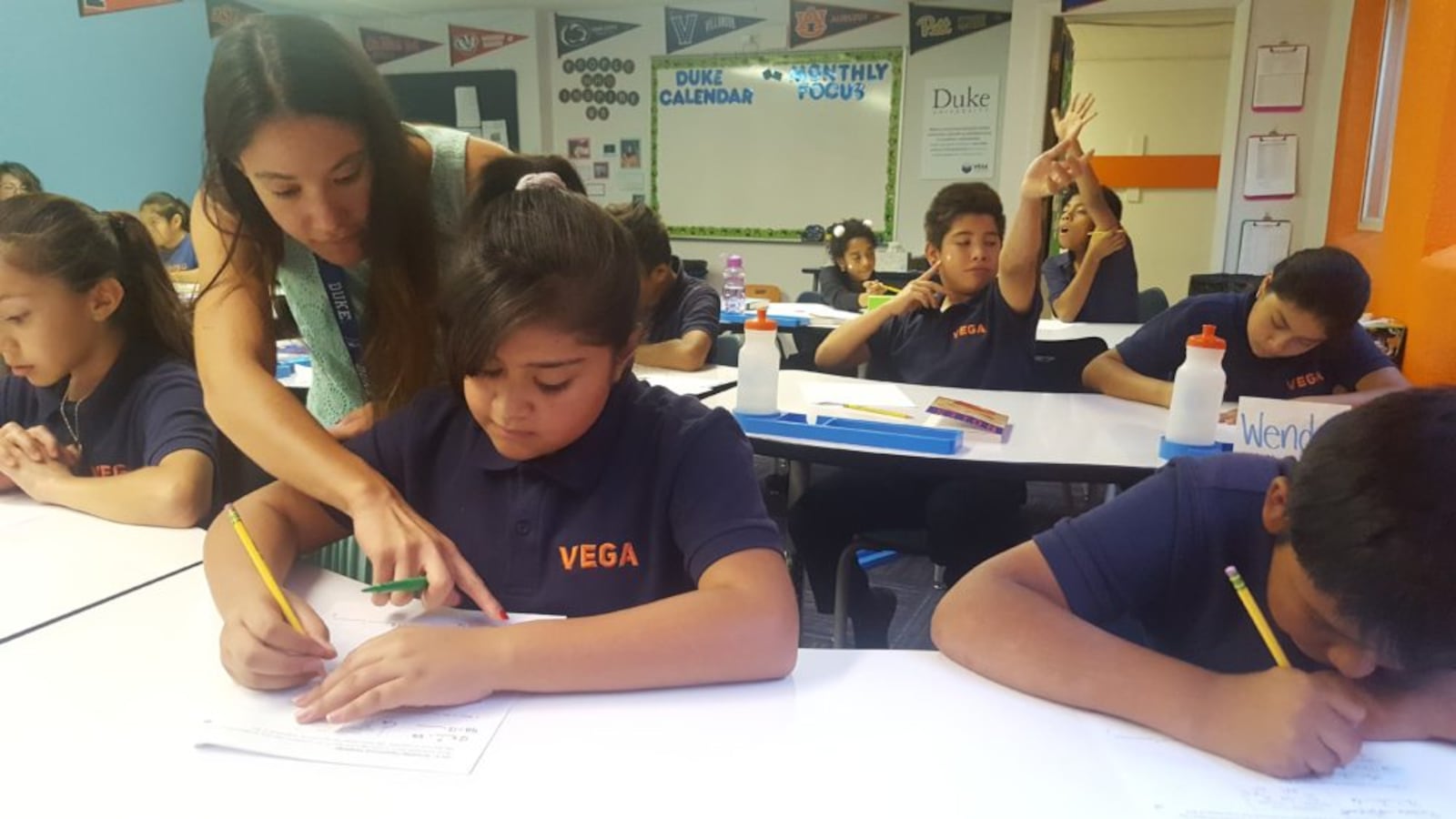

Back in class, students sit in classic rows facing the front of the class and stare at a timer teachers set for each assignment or problem they have to solve. When the teacher wants to get their attention again, students repeat a cheer or chant, she leads a sequence of clapping, and then they clasp their hands together in front of their chest.

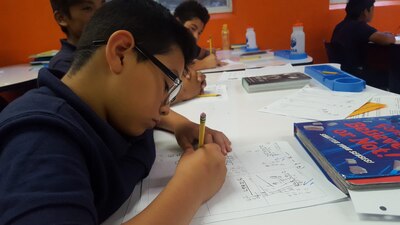

In class recently, when Gabrielle Mahon, the sixth-grade teacher, asked students what they had noticed in the division problem they had just done, several hands shot up. She called on one boy who said he noticed that “the six kept going.”

When she prompted him to elaborate what he did about it, he said, “I put in a repeater bar,” a math symbol to indicate infinite repetition of a digit.

“I’m proud of you,” the teacher told the smiling boy. Other times, teachers would start class cheers when students could answer correctly.

When students have a good response to a problem, or do something to go above and beyond, teachers can also dole out points. Students can use the points they accumulate to “purchase” prizes the school has gathered, such as tickets to an amusement park.

Mullins said that although they have a stronger focus on math, teachers also work hard to motivate students to read. Last year, Mullins paid for customized Nike shoes for students who read one million words — verified after students take a quiz for every book they read.

Twenty students, almost half of the school’s fifth graders, earned the shoes, she said.

“They’re proud of it,” Mullins said. “We try to make being nerdy cool.”

The school initially hit a bump in the road last year. Mullins fired the school’s lead math teacher at the end of October, and then decided to run the math program herself. (Mullins has a background as a math teacher).

“We do have a lot of autonomy,” Mullins said. “That’s something really powerful.”

Not all Vega teachers are licensed or trained traditionally, but the school provides a lot of coaching. Some teachers also go to visit other high-performing schools across the state or country.

Teachers at Vega practice their lessons in front of staff before they present them to their students. And many times, there are two teachers in classrooms, with one teacher coaching the other.

Kristin Brady is one of the school’s math teachers who jumps into other math classrooms to help “live-coach” teachers. She said one of the most important parts of their class structures is that they include skills review for the first 40 minutes of each 90-minute daily class.

“Today it’s dividing with decimals,” Brady explained to a visitor one Wednesday morning. “The teacher saw we need to reintroduce this skill, by looking at exit tickets from every class, so it’s data-driven instruction.”

Vega then uses the twice-a-week remedial math time to give students more practice on skills teachers identify as a common problem. Students sometimes practice math skills on laptops using math games or the online tutorials of Khan Academy.

This year, as the school is growing, Mullins said she expects student achievement to remain high and for students to continue making large gains.

To further boost learning, this year Vega hired another parent as a paraprofessional. Now four parents at the school work as teacher aides.

“One thing we saw was that having more paraprofessionals was really effective,” Mullins said. “Because they’re from the community, they naturally connect really well to our students so their small group time can be really meaningful.”

At the same time, she said, the training the school gives those parents on how to help in the classroom also helps them better work with their own children at home.

“We’re staying true with everything that was effective last year,” Mullins said. “It’s a very bright spot for our community here in Northwest Aurora.”