The Denver school district raised its bar this year for what it deems a quality school — and the number of schools meeting that bar plummeted, according to ratings released Friday.

Even though districtwide elementary and middle school test scores rose last spring, just 88 of Denver Public Schools’ more than 200 schools this fall are rated blue or green, the top two ratings on the district’s five-color scale. That’s down from a record 122 blue and green schools last year, and lower than the 95 schools that earned those ratings in 2016.

Twenty schools this year are rated red, which is at the bottom of the scale. That’s twice as many as last year but not as many as earned a red rating in 2016.

Superintendent Tom Boasberg said the lower number of top ratings doesn’t signal that Denver schools are getting worse but rather that the district is ratcheting up its expectations — something it has been planning for years. Now, to get the district’s highest ratings, schools need to show that more of their students can read, write, and do math at grade level.

The ratings system, Boasberg said, “really expresses our shared aspirations as a community for the academic growth and performance of our students.”

“We think it’s very, very important for us to articulate clearly those shared aspirations, to establish goals for people to strive for, and to be very public about how all of us are doing,” he added. “I know that’s not easy. Any time … you set an aspirational goal, you don’t always achieve it. I don’t think the answer is to water down your aspirational goals.”

The ratings — known as the School Performance Framework, or SPF, ratings — matter for several reasons. Many parents use them to pick where to send their children to school, a decision that’s both easier and more crucial in a district that prizes school choice. If fewer parents pick a particular school, the school gets less funding, which means it could be forced to cut the teachers or programs that would make it a desirable choice in the first place.

The district also uses the ratings to determine which schools are struggling and in need of extra money or support — and which are so consistently low-performing that they should be closed. The school board is currently reevaluating its policy for when to close red-rated schools.

Denver’s ratings have long been controversial because some people think the way they are calculated presents an incomplete or unfair picture of a school’s quality. The ratings are overwhelmingly based on how students performed on state literacy and math tests the previous spring. This past spring marked the third year students in grades three through eight took a set of more rigorous exams known as CMAS.

Their performance on those tests has actually improved over time. The percentage of Denver students scoring on grade level in both literacy and math has inched to within a few points of the statewide average, narrowing what had been a wide chasm.

Denver students have also shown strong academic growth, a measurement that compares students with those with similar score histories. Strong growth indicates that Denver students, most of whom are black or Hispanic and come from low-income families, are making more progress in a year’s time than their academic peers across the state.

But because the district made it harder for schools to be rated blue, which means a school is “distinguished,” or green, which means it “meets expectations,” fewer schools earned top ratings. In fact, 37 percent of Denver’s 207 schools got lower ratings this year than last year.

Among them were some of the district’s large comprehensive high schools, including North High and South High. Both fell from a yellow rating, which means a school needs some improvement, to an orange rating, which means a school needs more improvement.

John F. Kennedy High went from orange to red, which means a school needs significant improvement. So did West Leadership Academy, one of two smaller schools that replaced comprehensive West High. The district has in the past closed schools with repeated red ratings.

However, it also targets low-rated schools for extra financial help, providing up to $1.7 million over five years to the schools officials deem most struggling.

Boasberg attributed the high school ratings slips to a poorer than expected showing on state tests. This was the first year Colorado ninth-graders took the PSAT test, a precursor to the popular college preparatory exam, and their growth scores were surprisingly low.

“The SPF reflects that,” Boasberg said, referring to the district’s rating system.

One high school principal expressed concern that the ratings put too much emphasis on test scores and not enough on graduation rates and whether a school’s graduates can go on to college without having to take remedial courses. Stacy Parrish, principal at High Tech Early College, said she believes those metrics provide a more accurate measure of high school quality.

“When we have an inaccurate assessment tool, we are at the mercy of the color we are given,” she said. “We need to be able to control our own narrative of what we’re doing in our schools. Because across the metro area, we are doing beautiful work.”

A smaller number of schools, 10 percent, earned higher ratings this year. They include the district’s most requested middle school, McAuliffe International, which went from green to blue.

The district raised its quality bar this year in several ways. For instance, it increased the percentage of elementary and middle school students who must score on grade level on the CMAS tests for a school to be rated blue or green. It used to be 40 percent. It’s now 50 percent.

If that doesn’t sound very high, consider this: Just 45 percent of students statewide scored at grade level on the CMAS literacy test this past spring, and only 42 percent of Denver students did. The percentages were even lower for the math test.

The percentage of students in kindergarten through third grade who must score at grade level on early literacy tests for a school to be rated blue or green increased, as well. That change came after parents and community leaders complained that last year’s ratings were inflated because the early literacy tests overstated students’ reading abilities.

There is another factor at play this year, too: an “academic gaps indicator” that measures how well certain groups of students are scoring on the tests compared with benchmarks and with their peers. The demographic groups include students of color, students from low-income families, students with disabilities, and students learning English as a second language.

If students in those groups aren’t meeting benchmarks or if the gaps between, say, students of color and white students at a particular school are too big, the school’s rating will be penalized. Schools must be rated blue or green on the academic gaps indicator to be blue or green overall.

This year, 22 schools that would have been green were downgraded a step to yellow because they scored poorly on the academic gaps indicator. (See box.) The 22 schools include the district’s biggest and most requested high school, East High.

This is the second year the district has used the indicator. Last year, nine schools were downgraded from green to yellow. Three of them — Bromwell Elementary, Teller Elementary, and Hill Campus of Arts and Sciences, a middle school — made enough progress toward closing gaps or boosting the scores of students in those groups to move back up to green.

As for the district’s lowest-rated schools, the Denver school board is set on Monday to discuss changes to its school closure policy, which has hard and fast rules for when to shutter or replace struggling schools. Board members agreed this year not to use those rules, which rely heavily on school ratings and have been criticized as harsh and inflexible. Instead, the board talked about taking other evidence into account, though it hasn’t yet decided how that will work.

It’s also not clear if the board will consider closing any schools this year. Back in June, board member Lisa Flores, who proposed suspending the rules, said school closure wasn’t completely off the table, especially if a struggling school also has low enrollment.

Under the suspended rules, nine schools with successive years of low ratings could have been eligible for closure or replacement if they earned a red rating this year. Only two did: Lake Middle School, a district-run school, and Compass Academy, a charter middle school.

The seven other schools did better. They include the large, comprehensive Abraham Lincoln High, which earned an orange rating, and Math and Science Leadership Academy, an elementary school that jumped up to a green rating this year.

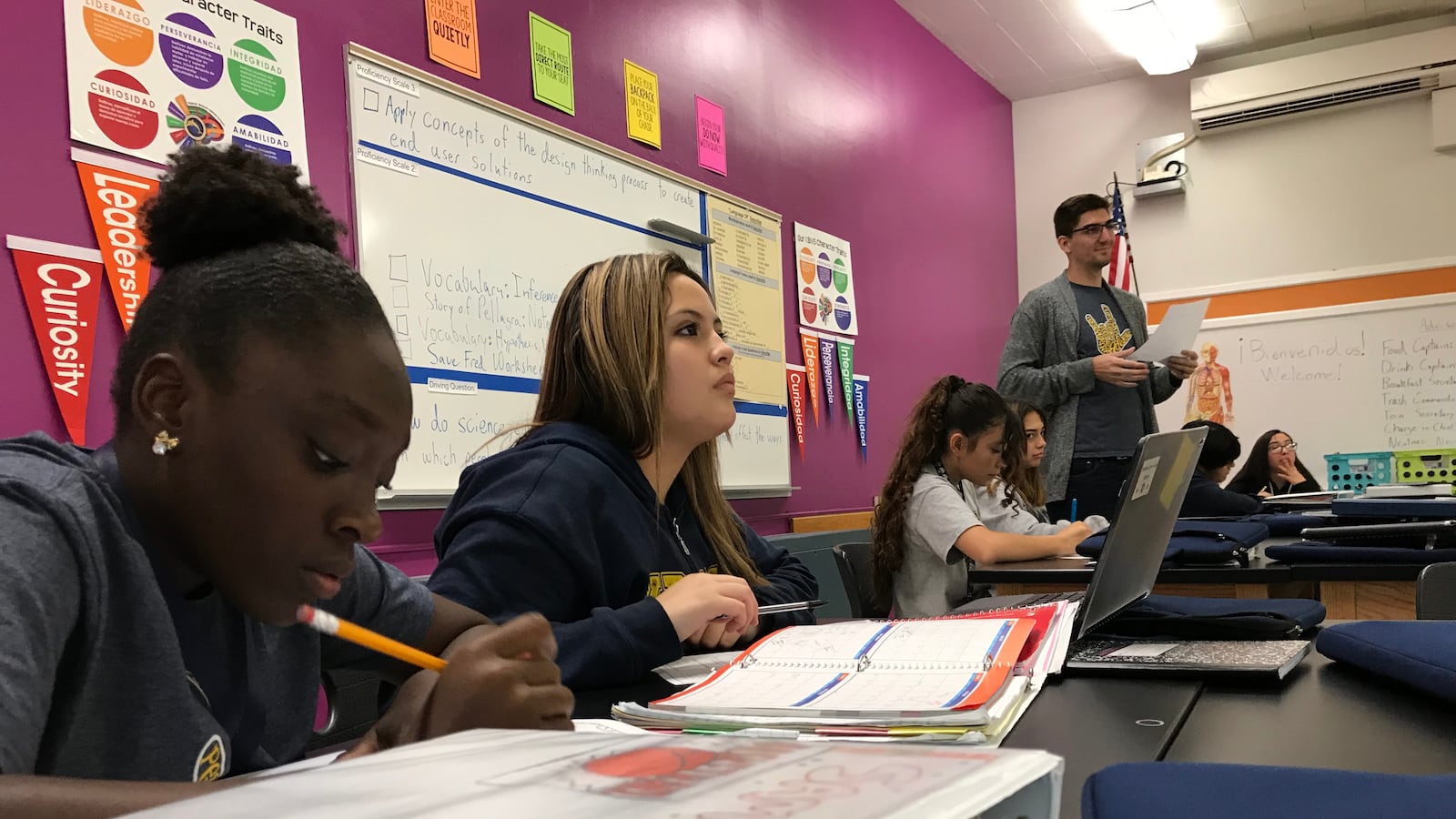

The district held a press conference about the ratings Friday at the Kepner campus in southwest Denver. That location is noteworthy because it represents one of the more controversial school improvement strategies deployed under Boasberg, who is stepping down as superintendent next week after 10 years at the helm of Denver Public Schools.

In 2014, the district began phasing out struggling Kepner Middle School. The district replaced it, grade by grade, with two new schools that share the building: Kepner Beacon, a district-run middle school, and STRIVE Prep – Kepner, a charter middle school.

Those two schools are green this year. Technically, so is Kepner Middle School, which doesn’t exist anymore. The last class of 132 Kepner Middle School eighth-graders moved on last spring, but their test scores were good enough to earn a green rating this fall.

“Turnaround is not an easy process and there’s lots of opposition,” Boasberg said. But he pointed out that in the case of Kepner, as the original middle school shrunk, the students who remained there thrived. “What turnaround is ultimately about,” he said, “is, ‘How do we get better opportunities faster for the students we serve?’”

Find your school in the spreadsheet below. Or look it up on the district’s website.