Denver schools with persistently low test scores will have to present detailed improvement plans this fall, but they no longer face automatic closure or replacement.

The Denver school board on Monday night agreed to a more flexible process for intervening in struggling schools. The changes mean the board will have more options and more discretion.

The process also seeks to give greater weight to information about a school’s culture, the demographics of the students it serves, and how school staff support those students socially and emotionally. In past years, school closure decisions were based overwhelmingly on academic factors, such how students fared on state literacy and math tests.

Ten low-performing schools are eligible for intervention this year (see box). The board is set to vote in December and January on which actions to take at each school.

How to improve struggling schools is a key question for urban school districts across the country. However, Denver Public Schools stands out nationally for adopting a policy in 2015 codifying that it should “promptly intervene” when a school is persistently underperforming and coming up with guidelines that set a clear path to school closure.

But the rollout of the policy was rocky, with critics attacking both the premise that closing struggling schools is good for students and the process the board used to do it.

The idea to change the process was first proposed in June by board member Lisa Flores. She cited several reasons, including frustration from teachers and parents who complained the board wasn’t considering the positive aspects of their schools, and a feeling among board members that the bright-line rules didn’t allow them to exercise their judgement.

Two other board members, Jennifer Bacon and Angela Cobián, spent the past several months working with district staff to come up with a new process. They presented it at a work session Monday night, and all the board members in attendance gave their approval. The 2015 policy will remain the same, but the guidelines for carrying it out will be different.

“I do not think the ‘why’ has changed, and the ‘why’ is incredibly important: It’s about serving our children and serving our children well,” board president Anne Rowe said.

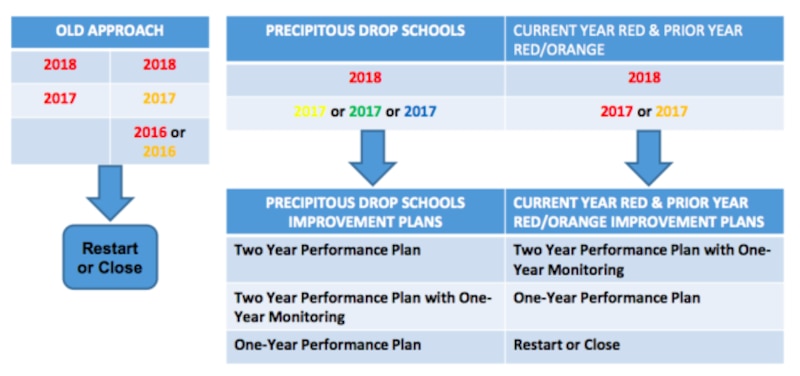

The old guidelines were strict but simple. They said that if a school earned the lowest rating on the district’s color-coded quality scale, denoted by the color red, for two years in a row, and its students did not show enough academic progress on the most recent state tests, the school would be designated for closure or replacement.

A school could also be closed or replaced if it earned a red rating in the most recent year and either a red or an orange rating, the second-lowest on the scale, in the previous two years. The ratings, released each fall, are largely based on state test scores.

Denver gives extra money — as much as $1.7 million over five years — to its lowest-rated schools in an effort to help them improve before interventions are necessary.

The new process is more complicated. It calls for red-rated schools to write an improvement plan with input from teachers and parents. That plan can pull heavily from the “unified improvement plan” every Colorado school must already submit to the state education department each year per state law.

A committee of district staff members, community members, and outside experts that could include retired district principals will evaluate the plan’s strength, as well as data about the school’s academics and culture.

Based on that evidence, plus interviews with school leaders and their supervisors, the committee will recommend an intervention to the superintendent. The superintendent will then make a recommendation to the school board, which will vote on it.

Using previous guidelines, the board voted in 2016 to close one elementary school, Gilpin Montessori, and replace two others, Greenlee and Amesse. In 2017, the only school that met the criteria was a charter school that decided on its own to close.

Under the new process, the board could still vote to close or replace a school that earned back-to-back red ratings. But it has other options, too. It could decide to put the school on a “one-year performance plan,” meaning the school would have a year to show improvement. Or it could choose a “two-year performance plan with one-year monitoring,” which would give the school two years to improve with a formal progress check after one year.

Those same options, ranging from a two-year plan to closure, would also apply to schools that earned an orange rating and then a red one. In that way, the new guidelines are harsher than the old ones, which required two years of orange ratings before a red rating.

The new guidelines also call for the board to intervene in a whole other set of schools: those whose ratings drop from one of the top three colors on the scale — blue, green, or yellow — down to red in a single year. Schools with such a “precipitous drop” would be put on either a two-year or a one-year performance plan, but they wouldn’t face closure or replacement.

Some board members struggled at first to understand the new rules. In explaining them, Cobián and Bacon referred to a graphic that illustrates the changes. Here’s the graphic:

The decision-making timeline is quicker for schools with multiple years of low ratings than it is for those that experienced a precipitous drop. Schools with multiple years of low ratings have until Nov. 12 to submit their improvement plans. The evaluation committee is scheduled to make its recommendations in early December, and the board is set to vote Dec. 20.

The schools in that category this year include two district-run schools, Stedman Elementary School and Lake Middle School, and one charter middle school, Compass Academy.

Schools that experienced a drop in ratings this year have until Dec. 10 to submit their plans. Recommendations are due in early January and the board is set to vote Jan. 24.

Those schools include three charters — STRIVE Prep – Excel High School, Girls Athletic Leadership High School, and DSST: Cole Middle School — and four district-run schools: John F. Kennedy, West Leadership Academy, and Collegiate Preparatory Academy high schools, and McGlone Academy, which serves students from preschool through eighth grade.

A school program developed by McGlone leaders was actually chosen last year to take over low-performing Amesse Elementary, which was one of two schools the board voted to replace under previous guidelines. McGlone was rated yellow last year but fell to red this year.