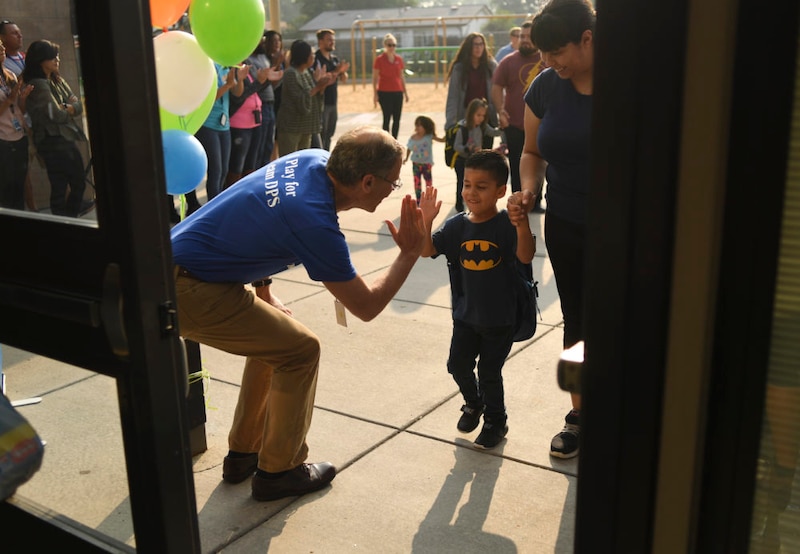

Tom Boasberg paused on his way out of the elementary school and held his phone to his mouth. The October sky was growing darker, and the Denver superintendent had just half an hour to get across the city in rush-hour traffic.

“Montbello High School,” he said in a low tone, enunciating each word so his phone would understand his destination.

GPS will still get you there, but the high school doesn’t technically exist anymore. In late 2010, nearly two years into Boasberg’s tenure, he advocated for closing Montbello High and replacing it with three smaller schools. The oft-cited statistic at the time was that just six of every 100 Montbello freshmen graduated ready for college. Boasberg — and a majority of the school board — thought the district could do better.

Now, in the waning days of his superintendency, Boasberg was headed back to Montbello for a celebration. The small schools that share the campus had just reopened their library after months of renovations and years of not having a full-time librarian. Plus, the football field was set to switch on its first-ever stadium lights — a big deal in a neighborhood with a proud history of excelling at high school sports and the packed trophy cases to prove it.

The upgrades were the result of relentless advocacy at public meetings by coaches, parents, and other residents. The scenes resembled countless others that played out over Boasberg’s near-decade at the helm of Colorado’s largest school district, which he led through a steady stream of big and sometimes unpopular changes to try to improve its schools.

His legacy is deeply entwined with those changes. Supporters hail him as the engine behind an urban success story with an impressive track record of turning around struggling schools. State test scores rose steadily under his watch. The high school graduation rate increased by 15 percentage points from 2010 to 2017. And district enrollment, once anemic, surged by more than 14,000 students, which some see as proof of parents’ confidence.

“There’s been a continuity over a period of time that provided stability, capable leadership, and direction,” said Bill Kurtz, founder of DSST, Denver’s largest homegrown charter school network. “That’s not the typical trajectory of a lot of large, urban public school districts.”

But critics point to stubborn problems that haven’t gone away. Schools, on the whole, remain segregated by race and family income in a district where a majority of the nearly 93,000 students are black and Latino and come from poor families. Test score gaps between more and less privileged students haven’t closed. And parents and residents of the neighborhoods most affected by controversial reforms continue to feel the district ignores their concerns.

Most everyone would lay the district’s failures and successes at Boasberg’s feet. However, even his harshest detractors agree that if nothing else, he was driven.

“He wasn’t a superintendent that just put out fires,” said Corey Kern, deputy executive director of the Denver teachers union, which butted heads with Boasberg on a multitude of issues over the years. “He had a clear vision of where he wanted the district to go.”

That’s perhaps surprising given that Boasberg, whose last day is Friday, never intended to be superintendent. He came to work for Denver Public Schools from a private-sector telecommunications company in 2007, recruited by then-Superintendent Michael Bennet.

The two are childhood friends. Boasberg, 54, grew up in Washington, D.C., in the ’60s and ’70s. Living in what he described as a newly integrated neighborhood and attending a newly integrated school — which was private, not public — he said he learned the importance of “not misjudging or undervaluing people because of who they are or the color of their skin, but ensuring people get the respect and opportunities they deserve.”

As a child, he dreamed of becoming a civil rights lawyer. But though he earned a law degree, he did not make his career in the courtroom. He worked for a time in Hong Kong, including a stint as a junior high school English teacher. He also served a higher-profile stint as the chief of staff to the chairman of what was then Hong Kong’s largest political party.

When Bennet asked him to join Denver Public Schools, Boasberg said he was drawn to it for the same reasons he’d once wanted to fight for people’s civil rights in court.

“As I got older, I recognized that, obviously, the law plays an incredibly important role” in driving equity, he said, “but I think our schools play an even more important role.”

At the time, Denver was the lowest-performing large school district in Colorado. It was also a few years into a big shift. Bennet was the first leader in years who hadn’t come from an education background, and he was shaking things up. He had a strategic plan full of lofty goals and some controversial ways to achieve them, including closing struggling schools. Student test scores, while still far below the state average, were beginning to show growth.

Boasberg was hired as the chief operating officer and tasked with overseeing the behind-the-scenes departments, such as food services and transportation, that make schools run. Gifted with numbers and a knack for efficiency, he earned high praise in that job, including from those who would come to dislike his policies as superintendent.

When Bennet was tapped in early January 2009 to fill a vacant U.S. Senate seat, the school board scrambled to find someone who would continue what Bennet had started. Board members quickly settled on Boasberg, who was voted in on Jan. 22.

From the start, Boasberg made plain his ambition.

“The opportunity for us, and the challenge, is not to rechart our direction or search for our destination,” he said after the vote, which his parents flew in from D.C. to watch alongside his wife and three children, “but to accelerate our reforms and do the work that will enable us to reach our goal of becoming the best urban district in the nation.”

Both supporters and critics view Bennet and Boasberg as something of a package deal. When asked to reflect on Boasberg’s tenure, most people start with Bennet. But while the two remain closely aligned on policy, their personalities are vastly different.

Deputy Superintendent Susana Cordova, who is thought to be on the short list to succeed Boasberg, provided an evocative example.

“One of my strongest memories of Michael Bennet is if you were in an elevator with him, he talked to everybody,” she said. “Tom is not nearly as extroverted, but he’s very approachable.”

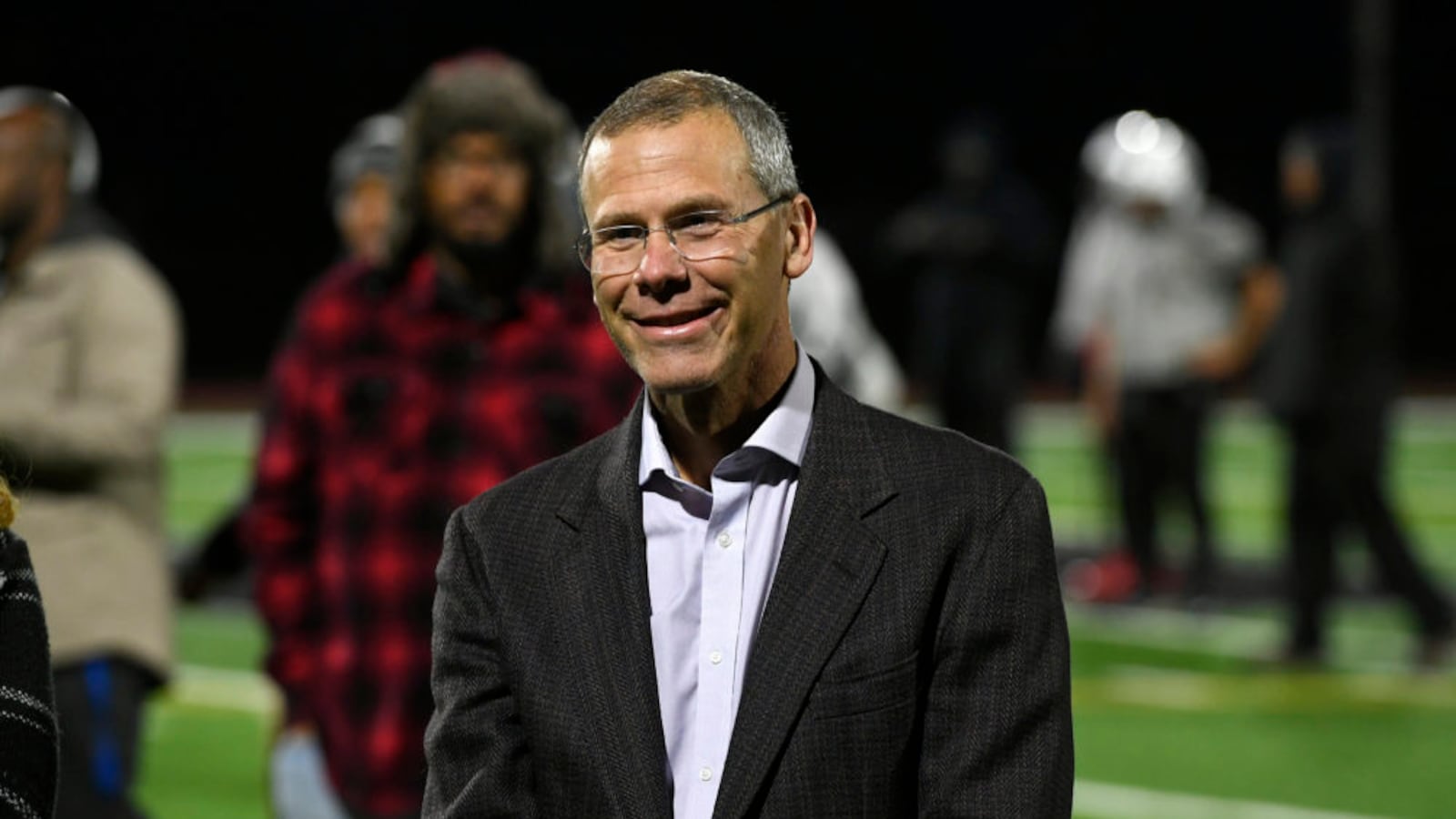

Tall and fit, with rimless glasses and short hair that has grown more gray over the years, Boasberg often dressed for the job in khakis and polo shirts. When he showed up at a middle school in a suit and tie last week, people remarked on his attire.

He’s more comfortable with data and details than with crowds, though longtime observers note he’s gotten better over the years at addressing packed auditoriums and schmoozy fundraising galas. He’s a naturally soft speaker, a patient listener, and a deep thinker. His default expression is serious, but he’s also quick to crack a joke (often of the dad variety).

“He’s articulate and charming,” said Paul Hill, founder of a Seattle-based think tank called the Center on Reinventing Public Education, who has known Boasberg for years and supports his reforms, “but he’s not somebody that gets the troops riled up.”

He is somebody who gets things done. For his entire tenure, he had the backing of a majority of the district’s seven-member school board, and Denver voters twice approved tax increases to funnel more money into the schools. The initiatives he successfully pushed for include:

- Putting in place a universal school choice system that allows families use a single form to apply to any of the district’s more than 200 schools, including charter schools.

- Collaborating with charter schools by sharing district tax revenue and space in school buildings in exchange for the charters serving more students with disabilities and students learning English as a second language.

- Granting the principals of district-run schools autonomy to choose their own curriculum and teacher training, and giving them more control over their school budgets.

- Closing both district-run and charter schools with persistently low test scores — and in some cases, replacing them with schools the district deemed more likely to succeed.

Many of those elements make up what’s known as the “portfolio strategy” for managing schools, and Denver’s deft execution of the model has made it a darling among charter school advocates. It has also made the district a cautionary tale to traditionalists and teachers unions who think independently run charter schools are “privatizing” public education.

For his part, Boasberg doesn’t want the portfolio strategy to be the thing that defines his legacy.

He points instead to much lower profile, more methodical work as his biggest achievement: a collection of district programs meant to raise the quality of its teachers and principals, which research shows is one of the most important factors in student success.

“Above all, it’s been around talent,” Boasberg said of the district’s strategy, and “just a real deep belief that this work is extraordinarily hard and challenging. The level of skill we need from our teachers, our school leaders, our district-level folks is very, very high.”

The initiatives include a cadre of residency programs, some of which give student teachers hands-on experience in the classroom and another that allows aspiring principals to spend a year working under veteran school leaders who act as mentors. Three-quarters of the new principals hired this year came up through one of the district’s programs.

One of the initiatives Boasberg is proudest of has standout teachers spend half of their time teaching students and the other half coaching other teachers. The arrangement is meant to help the other teachers improve and keep the district’s strongest teachers in the classroom.

Justin Jeannot, a teacher coach at Abraham Lincoln High School, said the opportunity to become a leader without having to give up teaching has kept him in Denver Public Schools.

“I have found purpose and a home in teaching students,” said Jeannot, who became a teacher after a career in engineering, “but it has been much nicer to be in a district that really is trying to be on the cutting edge of harnessing the leadership power of their teachers.”

Counted among those who think Boasberg will leave the district in better shape than he found it are school principals who took advantage of the flexibilities he afforded them, the founders of Denver’s biggest charter school networks, and advocates who believe so wholeheartedly in the portfolio strategy, they wish Boasberg would have been even more aggressive.

They see his legacy as one of setting aside ideological squabbles about which types of schools — charter or traditional — are best, and instead focusing on what would serve students.

“It’s always been about quality for him, not about ideology,” said Chris Gibbons, the founder of STRIVE Prep, which began with a single charter school in Denver and now has 11.

Mike Vaughn, who served as Boasberg’s chief communications officer for five years, said although his former boss had good political instincts and was able to anticipate who might be mad about a particular decision, “his calculus was always a family calculus: ‘How can we better serve families and give our families better schools?’”

Many say Boasberg has done that. A decade ago, a quarter of the city’s school-age children didn’t attend Denver Public Schools. Their parents opted instead for private or suburban schools they thought were better. That’s no longer the case.

“What’s happened in this era over the last 10 or 13 years is there’s an expectation that if you live in Denver, you should be able to send your kid to a good school,” said Van Schoales, CEO of A Plus Colorado, an advocacy group that supported many of Boasberg’s initiatives.

Others said Boasberg will be remembered for decentralizing district decision-making and pushing his school principals to think like entrepreneurs.

“One of his big mottos was, ‘Don’t wait, lead,” said Sheldon Reynolds, principal of the Center for Talent Development at Greenlee, a district-run elementary school that had a history of low test scores. Reynolds competed for the chance to restart it with a new program. “To know that from the top down, that’s the message — that spoke to me.”

Still others pointed to Boasberg’s commitment to equity, which included giving schools extra money to educate students with higher needs, such as those living in poverty, and doling out millions of additional dollars each year to the most academically struggling schools.

Equity is one of the six shared core values that district employees chose in 2012. Boasberg remembers the day that a thousand people brainstormed them in a huge banquet hall as one of the most fun of his tenure.

The core values have given way to a tradition where employees shout out their colleagues for demonstrating one of the values, which earns that person a small pin to fasten to their work-badge lanyard. Boasberg’s lanyard is full of them.

“Everyone who comes to work in the Denver Public Schools is extraordinarily mission- and values-oriented. That’s why we’re here,” Boasberg said, reflecting on what prompted the tradition. “What we sought to do is to say, ‘What an unbelievable strength that we have. How do we bring that together? How do we celebrate that?’”

That feeling is one of the things Boasberg said he’ll miss the most about working for the district. He does not have immediate plans for what he’ll do next beyond spending more time with his wife and kids. The family lives in Boulder, a city 30 miles northwest of Denver.

“That thought of getting out of bed on the morning of the 20th — probably I’ll get up a little bit later that morning — but I will deeply, deeply miss the shared mission here and the incredible group of people,” Boasberg said, referring to the day after he steps down.

Teacher Rebecca Erlichman said she’s appreciated having a shared vision under Boasberg.

“Even when you’re super stressed out, you know you’re all working toward a common goal,” said Erlichman, who is in her 11th year of teaching at Godsman Elementary School. “There’s something that’s really empowering about that.”

But not everyone felt empowered by Boasberg. Students, parents, teachers, and residents whose schools and neighborhoods were in the crosshairs of his most controversial policies say he will be remembered for disregarding community voice.

Time and again, they said, district officials called meetings to gather community feedback on an unpopular proposal, dutifully wrote down people’s concerns in colored marker on white butcher paper, and then did whatever they were going to do anyway.

“You get a dog and pony show: D.P.S.,” said Jeff Fard, a Denver Public Schools graduate, parent, and black community activist. “I’ve sat through too many of those meetings where they’re listening to the community and they go out and do the exact opposite.”

“It doesn’t matter if you speak in a low, soft tone to our faces,” said Candi CdeBaca, a graduate who founded a nonprofit that trains youth to advocate on education issues. “What matters is what decisions you are making, or you are failing to make, behind closed doors.”

Even those who think Boasberg was a great leader admit that community engagement was an area of weakness for him.

“Maybe it was the type of decisions we had to make that were really hard,” said Mary Seawell, who served on the school board from 2009 to 2013 and was a Boasberg ally. But, she said, “it didn’t get better, it just deepened. I’m talking about parents who walked in, in good faith, to a gymnasium and ended up leaving disappointed.”

Recently retired teacher Margaret Bobb, who taught in the district for decades and was active in the teachers union, said teachers often felt the same way. Boasberg’s support for evaluating teachers based on student test scores, and his defense of a pay-for-performance system that some see as favoring one-time bonuses over salary raises, made his insistence that teachers are the most important ingredient in a good public education seem disingenuous, she said.

“As I reflect on Tom, it’s been 10 years of lip service to teachers but not anything tangible that shows he believes in their intrinsic value,” she said.

Others say that for all his talk of equity, Boasberg did not do well by teachers of color. Recent efforts to diversify the teaching force have barely moved the needle, perpetuating an environment where 76 percent of students are students of color but 73 percent of teachers are white. A report commissioned by the district in 2016 found that black teachers, who make up about 4 percent of the teaching force, felt isolated and passed-over for promotions.

Some educators of color have another interpretation of the district’s acronym: Don’t plan to stay.

Still others blame Boasberg’s commitment to school choice for exacerbating gentrification in Denver by making it easier for wealthier families to move into working-class neighborhoods, knowing they don’t have to send their children to the neighborhood schools.

Critics say all of that has hurt students of color and those from low-income families. While their test scores have risen over the years, they continue to lag behind those of their white and wealthier peers. Black and Latino students, and those living in poverty, have also borne the brunt of the district’s practice of closing low-performing schools.

Azlan Williams was a junior at Montbello High in 2010 when Boasberg proposed phasing it out and replacing it with three smaller schools. He went with his parents to the community meetings, and he remembers the anger and the pleas for more time to turn things around. Williams, who was a good student and star basketball player, also remembers the disappointment when they didn’t get it, and how his school, home of the Warriors, felt different after that.

“It was like the air came out of the school,” he said.

More than half an hour after leaving the elementary school for the Montbello campus, Boasberg walked into the new library around 6 p.m. There was comfy new furniture, $30,000 worth of new books, and five new flat-screen TVs that students in a book club organized by the new librarian used earlier that day to Skype with the author of a novel they’d just read.

The hard-won renovation “restores that sense of respect that the children do deserve nice things,” said librarian Julia Torres, who previously taught English at one of the schools on the campus. “This has been a huge confidence booster.”

Boasberg argues that the closure of Montbello High achieved its intended goal: better opportunities for the students in far northeast Denver. He points to the numbers as proof. In 2010, 333 students graduated from high schools in the region. This year, 768 did.

“Students are feeling more challenged, they’re getting more individualized supports, and the culture at our secondary schools is stronger,” Boasberg said recently.

There were no big speeches in the library, no ceremonial ribbon to cut. Just chit-chat and a tray of finger sandwiches. As the sky turned black, a small group headed outside. It included Boasberg; his deputy, Cordova; two school board members; three principals; and two of the football coaches who’d agitated hardest for the changes.

The field was flooded with light so white and sharp that it made everything look as if it were in high-definition. The head coach trotted over to shake Boasberg’s hand. It was a much different scene than when the coach had shown up at school board meetings to air concerns that his players, who come from several small schools but play together as the Warriors, had no lights and varying bell schedules that made it hard for everyone to get on the field before dark.

“I don’t have nothing else to ask you for,” coach Tony Lindsay said, laughing and grasping Boasberg’s arm, his breath visible in the chilly night air. “Now I gotta do my thing.”

Boasberg and the others watched the players practice for a minute before huddling in a circle. The principals thanked the district. Boasberg thanked the principals. He also thanked the coaches and community members for their advocacy — and their criticism.

“We needed to get to work here and make some really necessary improvements,” Boasberg said. “This is a night I will remember for a long time.”

Afterward, he stopped to chat with a group of teenage girls standing on the sideline. He asked what they thought of the lights. “Pretty good,” one said. And the library? The girls told him they didn’t go to school at Montbello. They went to a different small high school, one of the original three that had replaced Montbello High but had since moved to another location in the neighborhood. Their school, they said, doesn’t have a library.

As Boasberg turned to walk back into the building, he recounted the story to a school board member. Even though he was set to step down as superintendent in little more than a week, he hadn’t stopped thinking about the future of the district.

“I told them, ‘You’re next,’” he said.