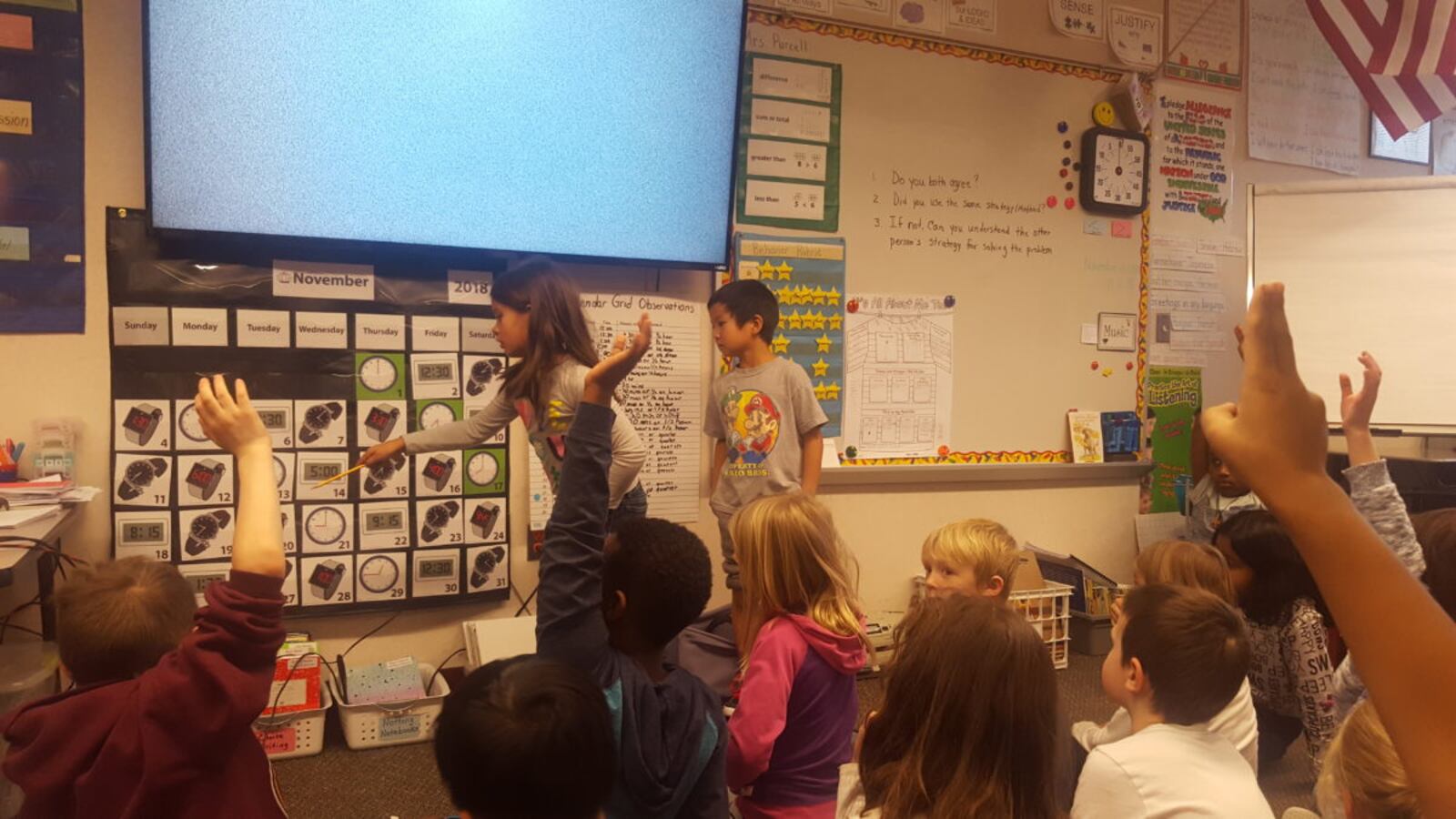

Second-graders at Aurora Quest scrutinized a complicated calendar on their classroom wall. Each day had a different kind of clock and a different background. Their hands raised impatiently, they described ever-more intricate patterns.

In a fifth-grade classroom across the school, students analyzed data on tablets and tested a series of claims against it. Were the claims true or false or did they just not have enough evidence?

In both classrooms, the students led the discussions, while the teachers hung back.

At the K-8 magnet school for gifted students in Aurora, students have access to higher-level courses than they might have at their neighborhood schools. Several of the older students are already taking high school courses, with one enrolled in a junior-level high school math class. Their progress means they’ll be able to take more advanced classes in high school that come with college credit.

It’s a benefit that comes with being labeled “gifted.” Yet Aurora Public Schools lags behind the state in identifying students who are gifted. Students of color, from low-income families, and who are not native English speakers are underrepresented among those who are identified as gifted in the district, often called one of the most diverse in the country.

“We had a system that was giving us the results that it was designed to give,” said Carol Dallas, the district’s gifted education coordinator. “That needed to be changed.”

So three years ago, the district paid an outside group to audit its gifted program. Based on those results, the district started testing more students, looking at new ways to identify gifted students, and developing ways to screen for non-academic talents. Aurora Public Schools is also taking a closer look at what teachers offer students in a typical classroom once they’ve been identified as gifted.

Aurora superintendent Rico Munn was recently recognized by state officials for his efforts around gifted education in the district.

Nationally, finding ways to identify students who are gifted among all racial, economic, or language backgrounds has long been a challenge. Several states, districts, and schools have tried various ways to increase testing, to train teachers on what to look for, and develop different ways to identify students. But the efforts haven’t always resulted in diversifying the gifted and talented population.

Sally Krisel, the National Association for Gifted Children’s board president, said that while many of the practices Aurora is rolling out aren’t new, educators across the country could be focusing more heavily on talent areas now because of correlating interest in looking at the “whole child” and not just their abilities in English and math.

But local decisions have created a lot of variance — even among neighboring schools and districts — as to how a child comes to be labeled gifted and what happens next.

She said some of the newest and promising research is looking at ways to identify giftedness among English language learners who might not be able to understand or express their strengths on traditional tests that necessitate English proficiency.

At Aurora Quest, Principal Kelsey Haddock said about 24 percent of students are English language learners.

The school doesn’t limit entrance to students who are already identified as gifted or talented, but looks at students who show “high potential” through other evidence such as grades, state test scores, or teacher recommendations. And more recently, school leaders said they have looked closely at how fast students are picking up the English language as one measure that could show their potential.

Those that do get accepted into the school often show rapid growth and rapid language acquisition, she said, and frequently end up identified as gifted or talented later on. Aurora Quest is also working on improving its outreach to families to let them know the school exists.

As a district, Aurora’s efforts also include work with University of Wisconsin researcher Scott Peters, in an attempt to outline more clearly criteria for identifying gifted students. One goal of his work, which is still in its early stages, is to develop criteria that will not depend on whether a student in the district is fully English proficient yet.

About 39 percent of the nearly 41,000 students in Aurora schools are English learners. Students in the district speak 167 different languages.

District officials also expect that identifying students in various talent areas will help recognize more students from diverse backgrounds.

Right now, Hispanic students make up 34.8 percent of students identified as gifted and talented, compared to 54.1 percent of the district population as a whole. Black students are also underrepresented, making up 12.4 percent of the students labeled gifted and talented students compared to 19.3 percent of the entire district population.

Colorado, using federal definitions, lists various talent areas where a student could be designated as gifted and talented, including in leadership, creativity, dance, performing arts, and visual arts.

Aurora has slowly rolled out rubrics for those talents in the last two years, often working with experts from the city or the local college to determine what to look for. In the area of performing arts, for instance, the district holds a performance festival where teachers, as well as actors and producers, critique students demonstrating their talents.

By the end of the school year, district officials expect to have rolled out another rubric for identifying students with exceptional leadership talents.

Aurora has so far evaluated 136 students for talents, and of those, the district has formally classified 62 students as gifted and talented or close enough to have “high potential.”

Dallas expects numbers to “explode” this year as more and more schools and students are learning about the opportunity.

“Students are talking about it,” Dallas said. “There’s just a buzz.”

Aurora officials are also looking at how instruction of gifted students is playing out in 10 schools with the highest numbers of gifted and talented students. The schools are making requests for funding that could help improve what they offer students, and district officials will track what helps most as they plan ahead.

It should all work together to better identify and serve students, district leaders said.

In one Denver school, principal Sheldon Reynolds has been doing similar work. His school, The Center for Talent Development at Greenlee, isn’t a magnet school, but a traditional neighborhood school in a high-poverty neighborhood that is gentrifying.

Reynolds said he worked with district officials in Denver to develop identification procedures at his school around leadership, athletics, arts, and language. He also worked on training his teachers to identify when a student might be gifted and talented.

And he’s using community partners to offer programming to all students to develop those talents. For instance, he said, he partnered with the police department to offer a running club, where students got exposure to community leaders from a variety of fields.

“We have a ton of kids out there that have talent that we need to be paying attention to,” Reynolds said. “And as we change this instruction, you benefit all kids.”