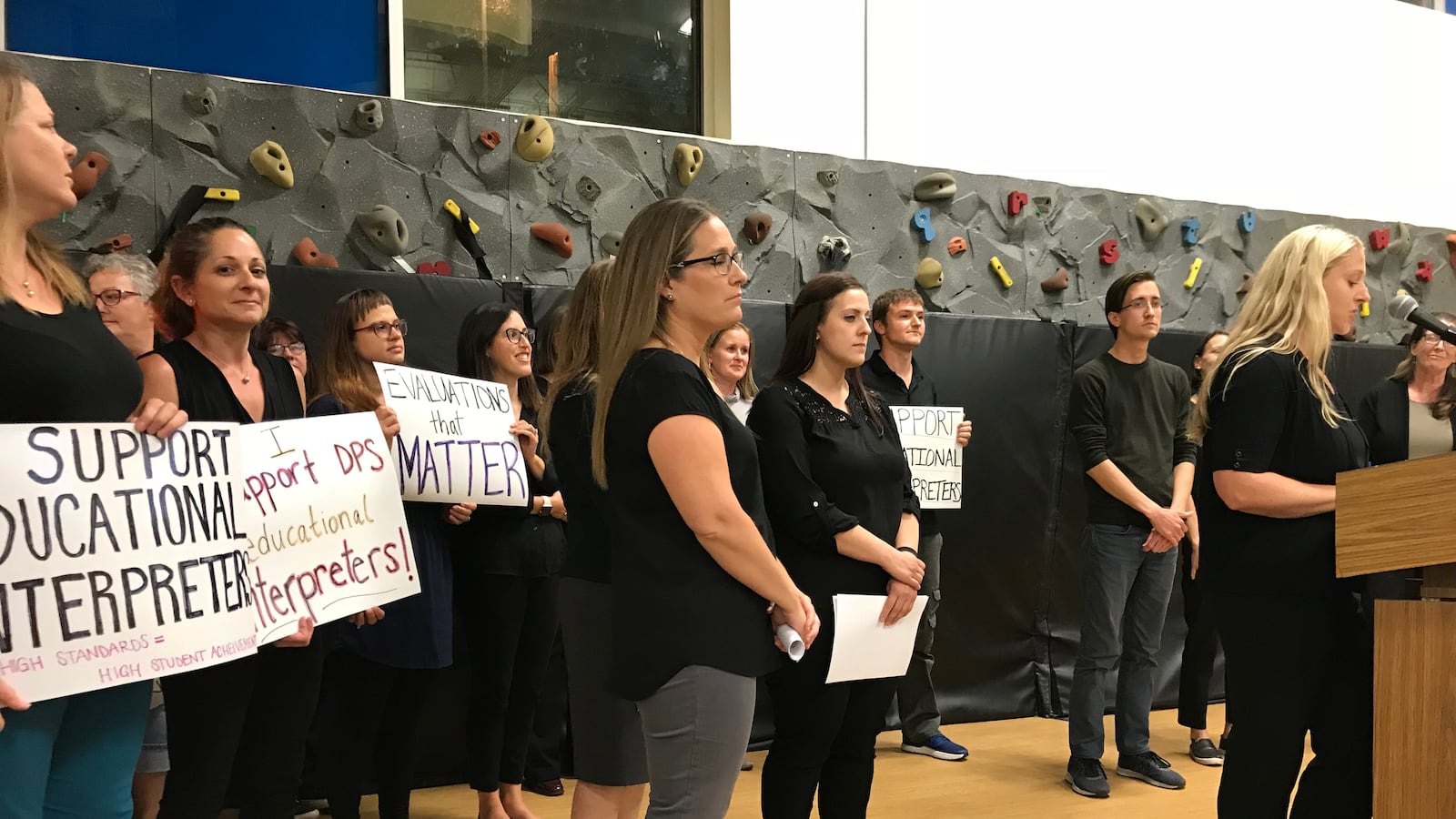

One evening in September, a group of school district employees clustered around a microphone in a gymnasium. They had recently gotten off work and were still wearing the head-to-toe black that allows their students to clearly see their hands when they’re signing. They were there to make a request of the Denver school board: to give them permission to join a union.

“The students we work with are some of the most vulnerable in the district,” said Tiffany Goll, who is one of 15 educational sign language interpreters in Denver Public Schools.

To better serve students who are deaf and hard of hearing, the interpreters want an improved evaluation system and a fair salary schedule — things they say would help attract high-quality job candidates and hold accountable those already working in the district.

The stakes are high: Statewide, students who are deaf and hard of hearing score lower on state literacy and math tests than their hearing peers do, and are less likely to graduate from high school. Denver interpreter Emily Wytiaz asked the school board that September night to recognize the unionization bid “so we can begin collective bargaining immediately.”

Three months later, that hasn’t happened. But the delay could be considered a small one when compared with the years-long fight to persuade Colorado to raise the professional standards for educational sign language interpreters, who play a crucial role for students whose disability is undeniable but whose small numbers mean they can be overlooked.

“It’s a small group of children who are affected, but it’s a significant concern,” said Sara Kennedy, executive director of Colorado Hands and Voices, a nonprofit organization that supports families of children who are deaf and hard of hearing.

Mackenzie Tucker, a 16-year-old Denver student who is deaf, recently gave emotional public testimony about the effect of having unqualified interpreters.

“I will give you a few points,” Tucker told the Denver school board. “One, you have caused me harm and you caused my school harm. Two, I went from being a straight-A student taking honors classes to failing my classes because of your educational interpreter. Three, I became anxious and depressed because of your educational interpreter.

“You are supposed to be educating kids, not causing kids harm.”

Just 134 out of more than 92,000 Denver students were identified last school year as having a hearing impairment as their primary disability. And not all of those students use interpreters. Most students have some hearing, according to the interpreters. Most students also use devices, such as hearing aids or cochlear implants.

But for students who use interpreters, they are “a lifeline,” said one former teacher of the deaf. Interpreters not only provide students with access to academic content and what the teacher is saying, but also to the incidental learning that comes from side conversations with friends, games played at recess, or the questions their peers ask in class.

“Hearing kids are listening to what other kids are saying,” Wytiaz said. For example, if one student tells the teacher they don’t understand something or can’t see the board, other students who hear it learn that they too can advocate for themselves. But without an effective interpreter, students who are deaf or hard of hearing can miss out on that learning.

Interpreters assist in other ways, too, helping students get drivers licenses or apply to college. Most deaf children are born to hearing parents, so interpreters sometimes act as communication conduits for families.

With young children, or those who have limited communication access at home, interpreters are often teaching language at the same time they’re interpreting content.

Interpreter Karen Perry demonstrated what that can be like: “‘Do you know this word?’ ‘No.’ Then you have to spell it. ‘Do you know the sign?’ ‘No.’” The interpreters said it can take dozens of times of showing a student a new sign before the student commits it to memory.

That takes considerable skill, and some advocates and parents worry that not all educational interpreters in Colorado possess it. Kennedy and others have long pushed the Colorado Department of Education to raise the criteria. To become an authorized interpreter, the state only requires a two-year college degree and a score of 3.5 out of 5 on a skills test.

But sometimes interpreters don’t even meet that bar. Advocates have collected plenty of anecdotal stories of cash-strapped school districts skirting the standards by hiring unauthorized interpreters as “signing paraprofessionals” or teacher’s aides.

“I know places in the state right now where they went to a parent with a special needs child of their own and said, ‘You did really great with your child. Would you like to interpret for this other little girl?’” said Leilani Johnson, a senior administrator in the University of Northern Colorado’s Department of ASL and Interpreting Studies, which offers a four-year degree in interpreting.

After years of lobbying from advocates and parents, the state in 2015 came close to raising its standards. The Colorado Department of Education even published draft rules that would have required a four-year degree and a score of 4 out of 5 on the skills test.

In a letter of support to state officials, Johnson emphasized the difference between an interpreter who scores a 3.5 and one who scores a 4. The former would only be able to convey “very basic classroom content” with “numerous omissions and distortions,” she wrote, while the latter could convey “much of the classroom content.”

“Our deaf and hard-of-hearing student population should not continue to experience inadequate access to their education,” Johnson wrote in her letter, which was also signed by the Colorado Department of Education’s deaf education specialist.

But the draft rules encountered significant pushback from a consortium of school district special education directors, the statewide teachers union, and other powerful education groups. The groups complained the changes would be too expensive (because districts would have to pay interpreters more) and make it harder for districts to find qualified candidates.

State officials shelved the proposal, promising advocates they’d revisit it soon. Three years later, the standards haven’t changed. Johnson said that’s frustrating given that Colorado was a pioneer in this area when its standards first went into effect in 2000.

“When you adopt early, you don’t change,” Johnson said. “That’s where Colorado is. They’re sitting at 2000. We’re two decades past that. That means two generations of children have finished their education and are leaving the school system.”

Paul Foster, head of exceptional students services for the Colorado Department of Education, said state officials haven’t forgotten about the issue. While there aren’t any high-profile efforts underway, he said officials have been “very informally” talking to special education directors about gradually raising the standard. As a former special education director himself, Foster said he understands the fears of escalating costs and exacerbating candidate shortages.

“A lot of people just want us to wave a magic wand and say we want to raise the standard,” Foster said. “I suppose we could do that, but what unintended consequences would we have?”

The Denver interpreters aren’t waiting. Though their focus is different — they’re not trying to change the state standards — they are also seeking to increase the professionalism and rigor of their jobs because they think their students deserve better.

Right now, the interpreters’ job performance is measured against goals they set themselves, as well as standard criteria such as whether they show up to work on time. But they want more. For one, they want to be evaluated on their actual skills: Are they communicating well with students? Are they collaborating well with teachers?

“We don’t just want a pay raise,” Goll said. “We want to be held accountable.”

Fourteen of the 15 interpreters who work for the district are in favor of unionization, said Goll, Wytiaz, and Perry. While unions can have a reputation for protecting ineffective employees, they think a skills-based evaluation system would actually help weed out bad actors.

“If it’s documented, there’s something to be done with that,” Wytiaz said.

Denver parent Mah-rya Proper understands well the desire to raise the standards for educational interpreters. She was a sign language interpreter herself for years before testing revealed that her oldest son, now 13, has progressive hearing loss.

Though her son wears hearing aids, he also uses an interpreter. He is the only deaf student at his school, and she said he does well academically. But Proper said it deeply concerns her to think that an interpreter who scored just a 3.5 out of 5 on the skills test could be interpreting less than 100 percent — maybe as low as 60 percent — of what his teachers are saying.

“It would be like telling a parent that we’re only going to teach your kid how to add numbers 1 through 6,” Proper said. “‘Numbers 7, 8, 9, and 10, those aren’t really that important.’”

She added, “It makes me so sad and frustrated for kids who are not having what they deserve.”