A coalition of advocates who favor early childhood discipline reform are gearing up to push for state legislation to curb suspensions and expulsions of preschoolers and children in early elementary school.

A bill to do that died in the legislature in 2017, a year after advocates tried without success to get legislation on the topic introduced. While the 2017 bill faced sharp opposition from rural school district leaders, among other groups, advocates said they plan to account for those concerns by specifying broader and more concrete reasons under which suspensions or expulsions of young children would be allowed.

“We’re feeling optimistic,” said Jake Cousins, spokesman for Denver-based advocacy organization Padres & Jóvenes Unidos, a member of the coalition.

He said he’s encouraged both by the makeup of the state legislature, which is controlled by Democrats, and Democratic Gov. Jared Polis’ plan to expand full-day kindergarten, which Cousins sees as a sign of the governor’s support of policies that promote school access. (The 2017 version of the bill had a bipartisan set of sponsors, but ultimately died in a Republican-controlled committee.)

The push for a state law limiting out-of-school discipline for young children aligns with ongoing efforts in many states and several large Colorado school districts to reduce suspensions and expulsions, and instead use alternatives such as restorative justice. While federal policy also endorsed such efforts during the Obama administration, citing the disproportionate impact of suspensions and expulsions on students of color, the Trump administration backed away from that guidance in December.

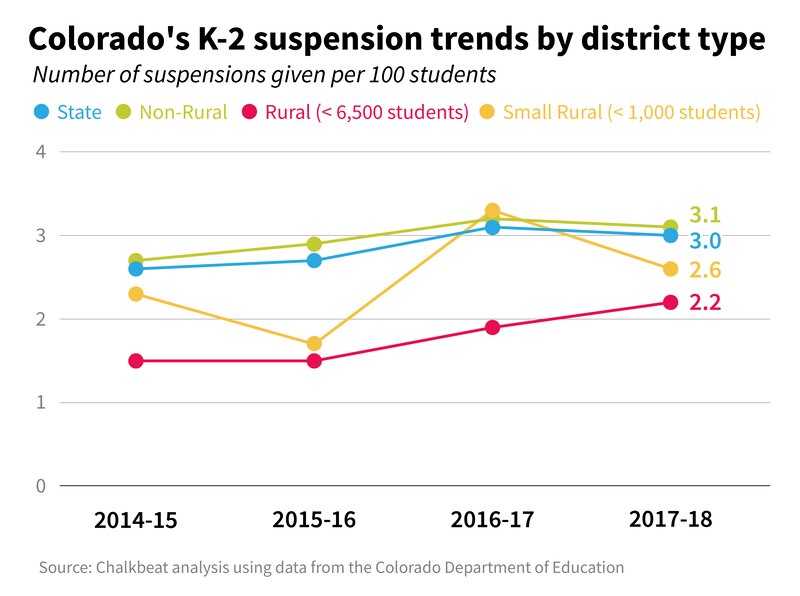

Last year, more than 5,800 suspensions were handed out to Colorado students in kindergarten through second grade, according to data from the Colorado Department of Education. That’s equivalent to three suspensions per 100 K-2 students — almost the same rate as in 2016-17.

These numbers represent the number of suspensions given out, not the number of students suspended. In some districts, individual students receive multiple suspensions during a school year.

Some districts have made big strides in reducing out-of-school suspensions given to kindergarten through second grade students, including Denver and neighboring Jeffco, the state’s two largest districts.

Last year, Denver reduced K-2 suspensions by 65 percent, to 157. Similarly, Jeffco reduced the number of annual K-2 suspensions by 42 percent, to 413.

Both districts have changed their discipline policies in recent years, with Denver adopting an official policy limiting out-of-school suspensions of preschool through third-grade students and Jeffco putting in place several measures to reduce the use of out-of-school suspensions in the early grades.

In other districts, suspensions of young children have increased. The Aurora district, where officials have also recently tried to reshape discipline practices, gave out 39 percent more K-2 suspensions last year than the year before, for a total of 501.

The behavior that gets little kids suspended varies. Often, it involves hurting staff or students, or causing frequent classroom disruptions.

Supporters of less punitive discipline say sending kids home from school for acting out doesn’t help them learn appropriate behavior, increases the likelihood they’ll be suspended again, and feeds the school-to-prison pipeline.

“I think it’s time for this bill,” said Heidi Haines, director of advocacy for The Arc of Colorado, which works on behalf of people with disabilities.

In Colorado and the nation, children with disabilities also receive a disproportionate share of suspensions.

When Haines tells people about her work on efforts to curb early childhood suspensions and expulsions, they’re often surprised it happens at all.

She said, “They make a funny face [and say] ‘Wait, people suspend and expel first-graders?”

But school district leaders who’ve pushed back against suspension and expulsion legislation in the past have argued that it would take away one of their few tools for addressing a student’s disruptive or violent behavior. They’ve also expressed frustration about the lack of staff and resources, especially in small rural schools, to handle students’ mental health needs.

Cousins said the coalition agrees with calls for greater mental health support for students and increased investment in the state’s schools, but not the view that suspension is a viable discipline tool.

Lots of research “suggests that removing a kid from a classroom at such a young age does a profound amount of harm,” Cousins said. “It’s not a tool in our minds because it’s just so ineffective.”

While this year’s version of the early childhood discipline bill hasn’t been drafted yet, leaders of the effort said it will include more exceptions to suspension and expulsion limits than the last attempt. These exceptions will likely allow suspensions or expulsions in cases involving dangerous weapons, controlled substances, or incidents that jeopardize the health and safety of others.

The 2017 version was similar, but included narrower grounds for suspensions and expulsions of preschool to second grade students. It prohibited expulsions except as allowed under federal law when kids bring guns to schools. Suspensions would have been permitted only if a child endangered others at school or posed a serious safety threat, or if school staff exhausted all other options.

Bill Jaeger, vice president of early childhood and policy initiatives for the Colorado Children’s Campaign, another member of the coalition, said the previous language worried some opponents who felt it was “too gray … too subject to interpretation.”

He said such feedback will make the new bill better than previous versions.

“I just don’t know if we’ll ever get past a different set of perspectives about whether state policy should be addressing this or not,” he said.

K-2 Suspensions by District

This chart shows the number of suspensions given, not the number of students suspended. In some districts, individual students receive multiple suspensions during a school year.