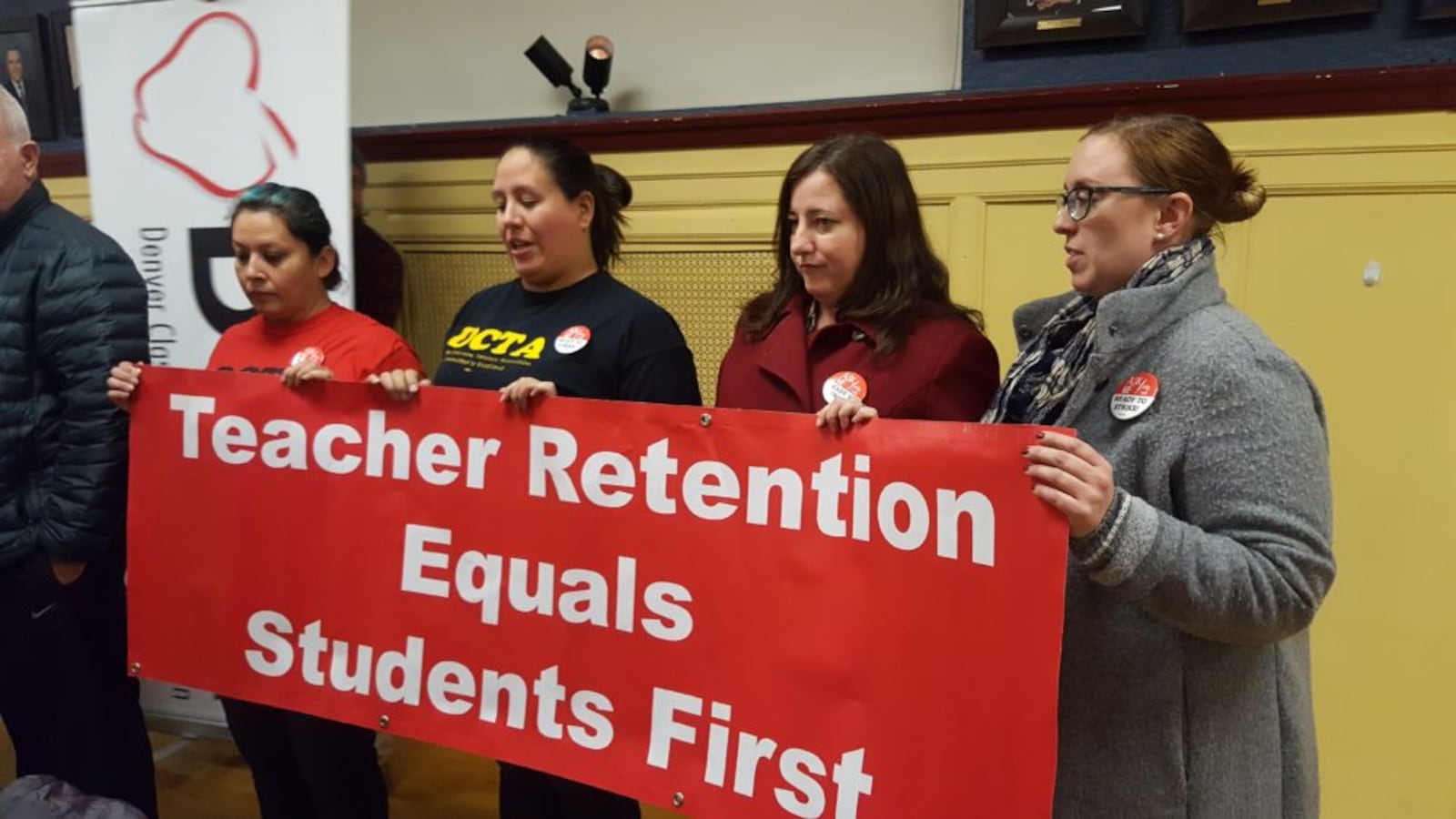

Denver teachers voted overwhelmingly to go on strike for the first time in 25 years. Amid a national wave of teacher activism, they’re seeking higher pay and also a fundamental change in how the district compensates educators.

Because of state rules, Monday is the earliest a Denver strike could start.

Ninety-three percent of the teachers and other instructional staff members who voted in a union election Saturday and Tuesday were in favor of a strike, according to the Denver Classroom Teachers Association. That surpassed the two-thirds majority needed for a strike to happen.

“They’re striking for better pay, they’re striking for our profession, and they’re striking for Denver students,” said teacher Rob Gould, a member of the union’s negotiation team who announced the strike vote results Tuesday night.

Denver Public Schools Superintendent Susana Cordova called the strike vote “not entirely unexpected.”

“From the correspondence that I’ve had with teachers by email and folks that I’ve talked with, it’s really clear there is a lot of frustration on the part of our teachers,” Cordova said.

She has pledged to keep schools open if teachers walk out. In an automated message to parents Tuesday evening, she made it clear that classes will take place as normal Wednesday and “into the foreseeable future.” The district is actively recruiting substitute teachers to fill in during a strike. It is offering to pay them $200 a day, which is double the normal rate.

The strike potentially affects 71,000 students in district-run schools. Another 21,000 students attend charter schools, where teachers are not union members.

Cordova said district officials plan to meet with Gov. Jared Polis on Wednesday and share a letter asking for state intervention, which could delay a strike. Denver Classroom Teachers Association officials also plan to meet with Polis Wednesday, according to union Deputy Executive Director Corey Kern.

The Colorado Department of Labor and Employment cannot impose an agreement between the district and the union, but it can provide mediation or hold hearings to try to bring about a resolution. In 1994, the last time Denver teachers went on strike, Gov. Roy Romer helped negotiate a settlement — after the court refused to order teachers back to work.

“It’s in everyone’s best interest to continue to work on finding the common ground,” Cordova said.

The strike vote in Denver comes after a weeklong strike by teachers in Los Angeles. It also follows a wave of activism and agitation for higher teacher pay that began sweeping the country last year. Here in Colorado, teachers from all over the state staged several rallies at the state Capitol last spring, demanding that lawmakers boost funding for the state’s schools.

The issue at hand in Denver is more localized. The teachers union and the school district had been negotiating for more than a year over how to revamp the district’s complex pay-for-performance system, called ProComp.

Late Friday night, an hour and a half before the most recent agreement was set to expire, the union rejected the district’s latest offer. Although the district offered to invest an additional $20 million into teacher pay and revamp ProComp to look more like a traditional salary schedule — which is what the union wanted — union negotiators said the district’s offer didn’t go far enough.

That rejection ended negotiations and set the stage for a strike. The union represents more than 60 percent of Denver’s 5,700 teachers, counselors, nurses, and other instructional staff.

Union officials did not release the number of teachers who voted on the strike or how many members it currently has. A spokesperson for the Department of Labor and Employment said strike votes are internal union matters over which the department does not have any purview. Kern said the vote was conducted electronically by a third party.

Cordova is in her third week on the job as superintendent. She has reminded the public repeatedly that she started her career as a Denver teacher and counts several teachers among her best friends. But her pledge to be more responsive than her predecessor, Tom Boasberg, has been tested in the bargaining process and now will be tested even further.

Denver teachers have long been frustrated by ProComp. In its most recent iteration, ProComp paid teachers a base salary and then allowed them to earn additional bonuses and incentives for things such as working in a high-poverty school or hard-to-fill position.

Denver voters passed a special tax increase in 2005 to fund the ProComp incentives. The tax is expected to generate $33 million this year.

But many teachers found ProComp confusing. Relying on bonuses and incentives caused their pay to fluctuate in ways that made financial planning difficult, they said.

Chris Landis, a fifth grade teacher at Colfax Elementary, said his salary has varied by as much as $5,000 from one year to the next in the four years he’s been teaching in Denver. He sees the union proposal as creating more stability over the long run, which makes the strike a risk worth taking.

“As someone who wants to be a teacher for the rest of my life, the union proposal has a lot going for it,” he said. “Education is worth fighting for. I’m willing to take a personal hit to guarantee the future for our kids.”

The union wants smaller bonuses and more money for base pay. The union also wants the district to spend roughly $28 million more than it currently does on teacher compensation.

The district’s proposal would have increased base salaries, too, but not by as much. And it would have kept the bonuses and incentives more robust. For example, the district’s offer includes a $2,500 incentive for teachers who teach at schools serving a high proportion of students from low-income families, while the union’s last proposal called for a $1,750 incentive.

District officials said that incentive is key to attracting and retaining high-quality teachers at high-poverty schools, where teacher turnover can be high, and Cordova does not want to compromise on that.

In the end, the union and the district proposals were separated by about $8 million. District officials said they couldn’t come up with any more money, and would already have to make deep cuts to invest the additional $20 million they proposed.

Teachers called their bluff, pointing to what they called a top-heavy administration and noting that $8 million is less than 1 percent of Denver Public Schools’ annual $1 billion budget.

The strike will put pressure on teachers, too, though. The union has a very modest strike fund. A Go Fund Me started on Jan. 16 had raised a little more than $7,000 when the vote results were announced.

“Everybody is stressed out” about going without pay, said Tiffany Choi, a French teacher at East High School, “but this is the sacrifice we’re willing to make.”

Correction: This article has been updated to reflect the most recent union proposal with regards to incentives at high-poverty schools.