The day after news that Denver teachers union members had voted to strike, Denver’s largest charter school operators reassured families their schools will keep operating as usual and sought to highlight their own efforts to better compensate teachers.

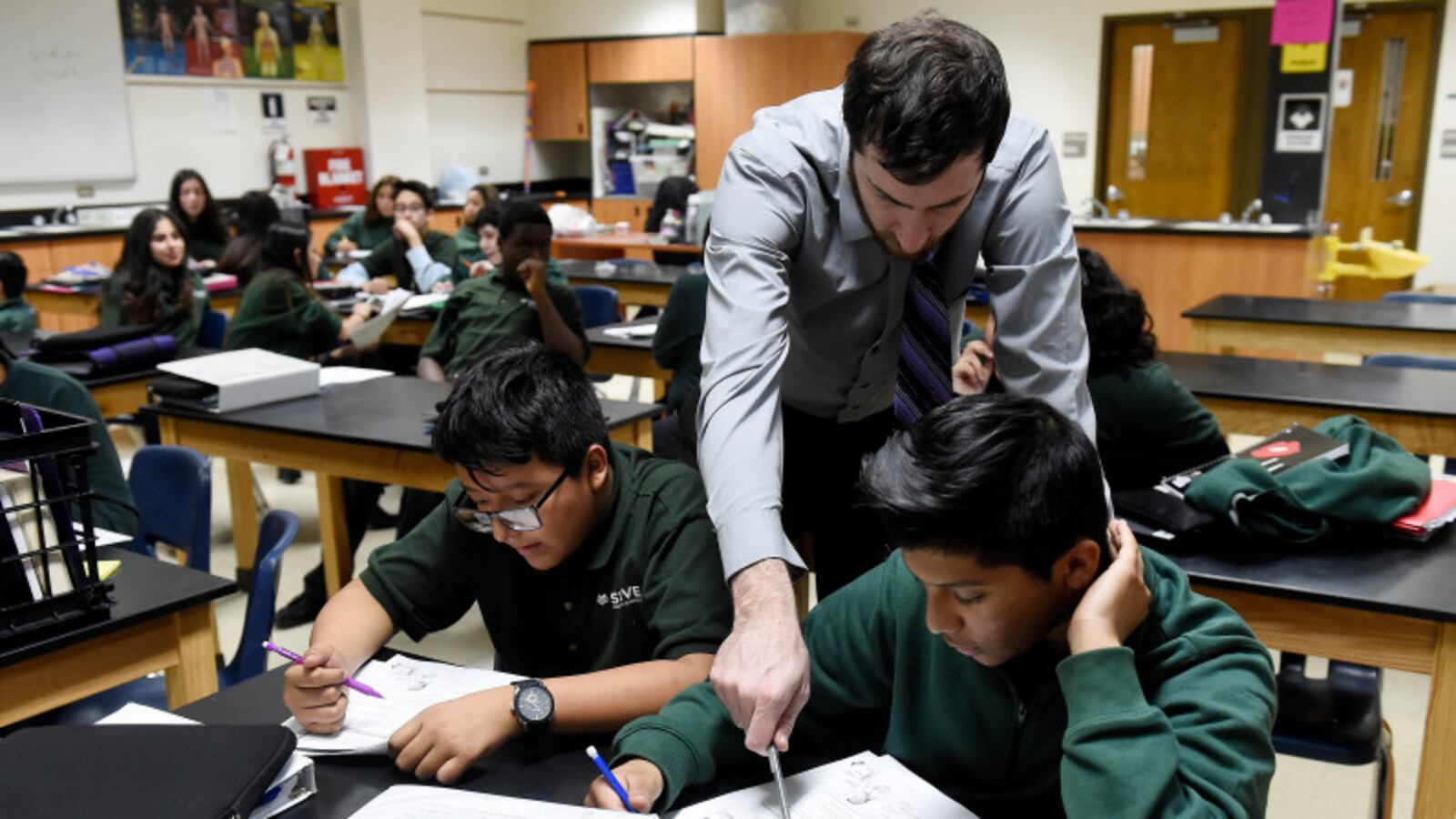

Both DSST Public Schools and STRIVE Prep — which collectively educate about 9,500 students at 25 schools — wrote emails to families and supporters Wednesday as questions swirl about the ramifications of a potential Denver strike at district-run schools.

The earliest a strike could start would be Monday, but Denver officials have asked for state intervention, a move that could delay any labor action.

Teachers at Denver’s 60 charter schools are not union members and won’t be going on strike.

But around the nation, unions have started to organize charter teachers, and the issue of teacher pay and how schools are funded has drawn more public attention.

While classes at charter schools wouldn’t be directly affected by a Denver strike, any labor action will still touch those students and their families. Many Denver charters share space with district-operated schools in district-owned buildings, and district and charter officials say they have been communicating about making sure things run normally.

“We remain very supportive of all Denver teachers and all Denver schools,” DSST CEO Bill Kurtz wrote in a letter also posted online. “Yet we share in the concerns of many throughout our community about the impact a strike will have on our students and families.”

While charter schools have been a factor in district-union negotiations elsewhere — including in Los Angeles, where a strike just ended — the focus is narrower here, on the district’s ProComp pay-for-performance system for district teachers.

Denver Public Schools has long embraced charter schools as part of its nationally known “portfolio” model that calls for giving schools autonomy, allowing families to choose among them, and then closing or replacing schools if they don’t make the grade academically.

The district also allows charters space in existing schools that have it to spare, part of a “collaboration compact.” Five of STRIVE Prep’s 11 schools are co-located with district schools. STRIVE CEO Chris Gibbons said DPS has conveyed that transportation, food services, safety and security, and facility management will be operating normally at all district buildings.

Kurtz said the district is “taking proactive steps to work with everybody and ensure students and families can get to their schools each day. So we feel good about that.”

A DPS spokeswoman confirmed the district has been communicating with charter schools housed in district buildings, but did not immediately provide more details.

Both DSST and STRIVE in their letters Wednesday mentioned the importance of paying their teachers well. DSST was more specific: Kurtz wrote that school officials last week committed to a 12 percent raise in teacher pay across the 15-school network. He described it as part of an effort over the last several years to boost compensation for all employees.

While STRIVE’s letter did not go into such detail, Gibbons said STRIVE is also planning average raises of 10 percent to 12 percent next year, a “significant” increase.

The charter network uses a performance pay system, with teachers eligible for raises based on a combination of teacher evaluations, test results, and other tools in specific content areas.

Charter school teachers are often paid less than district teachers. A 2016 report by the Colorado Department of Education found that the average Colorado charter school teacher earned $39,052 the previous year, whereas the average salary at a district-run school was $54,455. Kurtz and Gibbons could not immediately provide information about averages salaries at their schools.

Leaders from both Denver charter school networks say their efforts on teacher compensation are in response to broader state funding challenges and not connected to the DPS negotiations or the potential for a Denver strike.

Colorado voters in November rejected Amendment 73, a statewide tax increase that would have raised an additional $1.6 billion a year for schools. Even without that new money, the charter leaders said they know they need to do more for teachers.

“The degree to which public funding is paying for education in Colorado is reaching crisis state,” Gibbons said. “All of us watched Amendment 73 with a great deal of interest as a potential statewide and systematic solution to funding that would systematically impact teacher compensation. When that failed, we believed it was time to do everything we possibly could.”

Colorado doesn’t have unionized charter schools, though they do exist in other states. The nation’s first charter strike took place in Chicago in December, and another charter operator in that city is threatening one.

Last fall, the Denver teachers union used state public records law to obtain the names, email addresses, and salaries of every charter school teacher in the school district — a signal that the union plans to try to get charter school teachers to join. The Denver Classroom Teachers Association declined to say how it planned to use the information.