Criticizing the most recent teacher pay bargaining session as “political theater,” the head of the Colorado Department of Labor and Employment urged the Denver school district and its teachers union Monday to work harder to find common ground — even as he expressed skepticism that the two sides would reach a deal.

“While much of the public focus in this contract dispute has been on teacher salary levels, upon closer examination, it has been our observation that most of the points of contention are predicated on philosophy disagreements other than teacher pay,” state labor chief Joe Barela wrote in a letter to the two parties.

He added that, “Moving negotiations forward seems highly unlikely until both parties can get to a common starting point.”

Denver Public Schools has asked state labor officials to intervene in the dispute over how — and how much — to pay the district’s educators. The Denver Classroom Teachers Association wants the state to stay out of it. Union members voted last month to go on strike, but the action has been on hold while Colorado Gov. Jared Polis decides whether to get involved.

Polis has until Feb. 11 to decide whether to intervene, which could delay a Denver strike by as much as 180 days. The letter from Barela requests that the district and the union each meet with the governor early this week “to discuss the path forward,” and to review an “informal analysis” by state budget officials of each side’s proposal.

On Thursday, union leaders rejected the latest district offer, which called for investing $50 million more into teacher pay over the next three years. The offer represented movement by the district in the form of an additional $3 million for teacher pay in the 2020-21 school year, plus two additional years of cost-of-living raises.

Union negotiators called the offer a waste of time.

“The offer you have brought today is an example of your inability to listen to our educators,” lead union negotiator Rob Gould told Denver Superintendent Susana Cordova and her team.

He reminded them teachers had voted to strike. “From this day forward, you will have no choice but to listen,” Gould said.

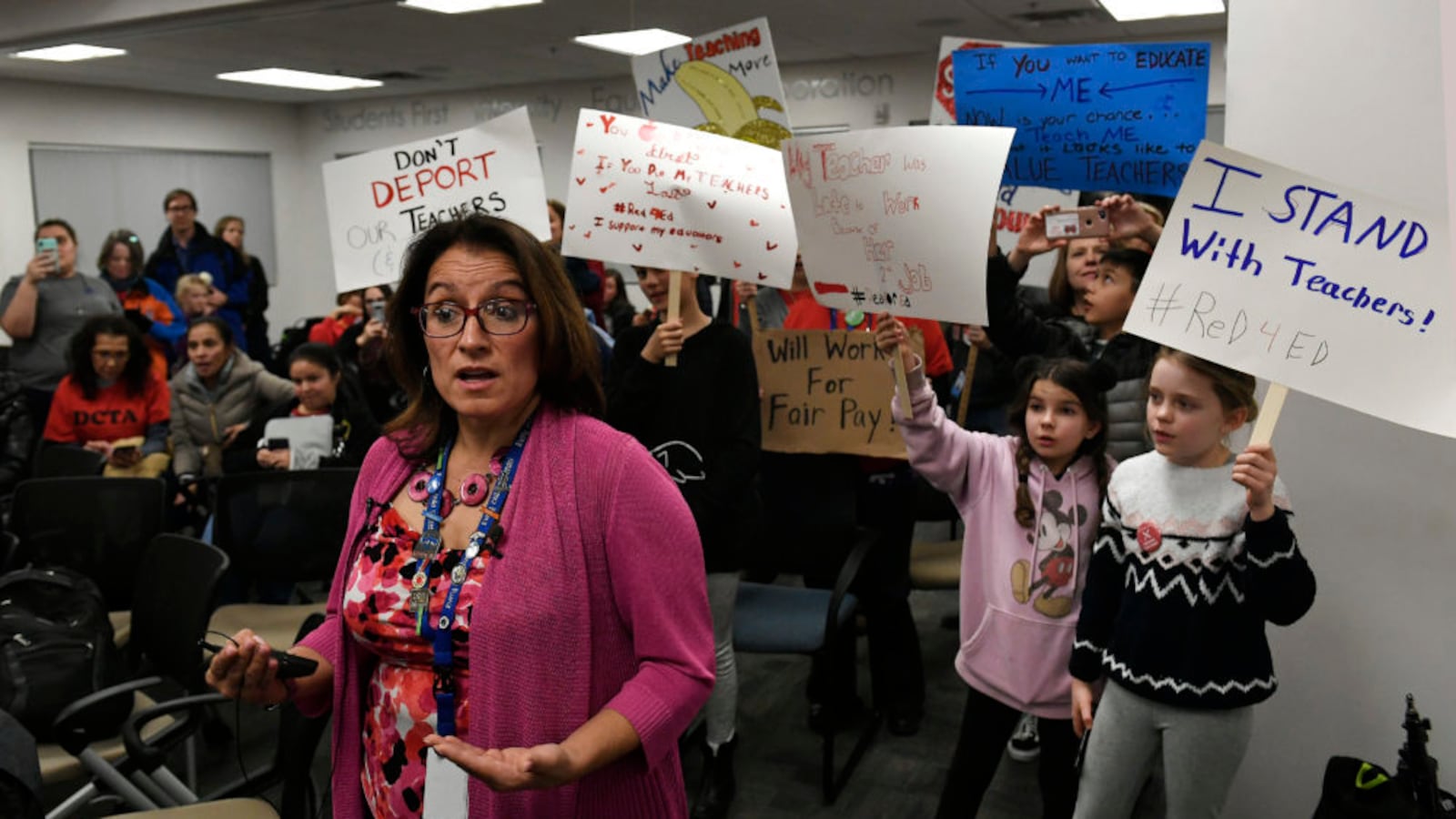

After talks ended that night, union supporters demonstrated behind Cordova and shouted “Shame!” as she spoke with reporters.

Barela said the tenor of that meeting was not encouraging.

“Last Thursday night’s negotiation turned into political theater at its worst, not meaningful negotiations,” he wrote. “This trend is very troublesome and weighs heavily on the state’s decision to intervene or not.”

Barela’s letter says Polis “supports workers’ rights, including their right to strike.” It also notes that Polis “joined Pueblo teachers on the picket line” when they went out on strike last year. State labor officials did not intervene in that strike, despite a request from the district.

One difference between Pueblo and Denver: the Pueblo teachers union had already engaged in what Barela called “an objective effort to arrive on mutual facts” with the district when teachers went out on strike. The fact-finding process has not yet occurred in Denver, and Barela noted that state intervention could bring that about.

“One reason the state may be compelled to intervene is that the state would be in a better place to ensure a process is designed to resolve disputes within the scope of the contracts at hand,” he wrote.

A statement from Denver Public Schools said district officials “believe that it would be better for everyone to get to an agreement before a strike,” and says officials would like to engage in “productive negotiations” about areas of disagreement.

But the Denver Classroom Teachers Association said Barela’s assertion that state officials would be better positioned to resolve the dispute was “misguided.”

“Denver teachers do not want the state to intervene in a strike because state officials cannot appreciate the full measure of concerns we have with the way DPS pays its teachers” and other educators, union president Henry Roman said in a statement.

At issue is a Denver Public Schools system known as ProComp that pays teachers and other educators bonuses and incentives on top of a base salary for things such as high student test scores, and working in a hard-to-fill position or a high-poverty school.

The disagreement between the district and the union is part financial and part philosophical. The union wants to shrink the sizes of the bonuses and put more money into base salaries, which it says are more predictable than bonuses that can vary from year to year and school to school.

The district agrees with raising base salaries, but wants to reserve more money for bonuses. For example, district leaders believe incentivizing good teachers to work in high-poverty schools is key to closing test score gaps between more and less privileged students.

Attached to Barela’s letter was a memo from the Colorado Office of Planning and Budgeting that analyzed the district and union proposals. State budget officials estimate the district’s proposal would cost $20.8 million in its first year, whereas the union’s would cost $28.4 million.

The memo highlights areas of agreement and disagreement between the two sides. Among the areas of agreement: a $750 incentive for teachers in “distinguished schools;” a $2,500 incentive for teachers in hard-to-fill positions, such as special education and secondary math; and a desire to significantly increase how much money the district spends on teacher pay.

However, the two sides disagree on the size of an incentive for teachers who work at high-poverty schools. The district has proposed $2,500, while the union has countered with $1,750. They also disagree on whether to offer an incentive to teachers to work at schools deemed “highest priority.” The district would like to offer those teachers an additional $2,500, while the union wants to spend that pot of money to increase the base salaries of all teachers.

Another “major issue in dispute,” the memo notes, are the mechanisms teachers can use to earn base salary raises. In addition to college credits, advanced degrees, and advanced licensure or certification, the union has proposed allowing teachers to earn raises for completing training courses. The district has rejected that proposal as too costly on the assumption that 80 percent of teachers could earn raises each year if that were allowed.

State budget officials pushed back on that assumption. In their estimation, based on how it works in other districts, only 10 to 20 percent of teachers would earn raises each year under the union proposal, at a cost of up to $2.8 million annually.

Budget officials said there appeared to have been “no substantial discussion” between the district and the union about what types of training could be used to earn raises. Having agreement on that could bring the two sides closer to a deal, or at least to shared financial assumptions, the memo said.

Read the full letter and budget memo below.