For the first time since the Denver teacher strike exposed divisions in their ranks, the 100 adults who make the Beacon middle school network run gathered in the same room.

Teachers, some still wearing red for the union cause, brought breakfast burritos to share. Upbeat soul music pumped through the speakers, an attempt to set a positive tone.

Speaking to the group assembled Friday for a long-scheduled planning day in the cafeteria of Grant Beacon Middle School, Executive Principal Alex Magaña opened by acknowledging the awkwardness that had taken a toll on a school community that prides itself on a strong culture.

Some teachers who had gone on strike — exhausted by the experience and exhilarated by the outcome — felt snubbed. Where was the celebration of what they had just fought for?

School administrators were smarting for another reason: A large number of teachers did not return to work on Thursday after the tentative pact was signed, making for another hard day.

Just as it was starting, the effort to heal the Beacon school community was stumbling a bit.

One day after the end of the three-day strike over teacher pay, students at the Beacon schools had a day off Friday, giving leaders the opportunity to begin repairing any damage done. The district administration shared resources with schools, too, including a “lessons learned” tipsheet from the recent Los Angeles teachers strike.

The challenge is proving unexpectedly daunting at the city’s two Beacon schools — Grant Beacon in southeast Denver and Kepner Beacon in southwest Denver — which share a common central administrative staff, approach, and mission to serve the city’s neediest students.

“It’s never been administration-versus-teachers, district-versus-teachers, in the culture we have created here,” said Magaña, who oversees the two schools. “We have a lot of good leadership, a lot of input from teachers. But this caught everyone kind of by surprise.”

By “this,” Magaña means the tension on the two campuses before, during, and after the strike that put Denver in an unfamiliar national glare. The 93,000-student district is better known for its unique brand of at times controversial education reform — of which the Beacon network is part — than it is for labor strife and division in the educator ranks.

As it became evident that the teachers union was intent on striking, Magaña said he sent a message to his teachers, staff, and administrators.

“I called it out two weeks ago: Be careful with what you say, because it’s going to cause harm and impact our culture,” he said. “Everyone has their own right to make their own individual decision. Respect it. And people were trying to respect it.”

From Magaña’s perspective, it didn’t always happen. At Kepner Beacon, where 96 percent of students qualify for subsidized lunches, the young corps of teachers “grouped together and suddenly had this camaraderie, which is something that is part of our culture and that makes us successful,” Magaña said.

All but a few Kepner Beacon teachers went out on strike. Magaña harbored concerns, though, saying some striking teachers “were guilting teachers into joining for solidarity.” Teachers who crossed picket lines told him they felt alienated, he said.

Linsey Cobb, a special education teacher and special education team leader at Kepner Beacon, disputes that. She said every teacher wholeheartedly supported each teacher’s decision.

Cobb herself was torn about striking. She said she stood with teachers fighting for a system they believed would pay them a better, fairer wage. But the third-year teacher ended up reporting to work as usual Monday morning, feeling too strong of a pull to fulfill her responsibilities supporting students with individualized education plans — the complex and sometimes confounding binding documents for students with special needs.

Cobb said she was not fully prepared by what she experienced that morning.

“Even though I am very close with my students, I felt incredibly isolated,” she said. “I got the weirdest feeling. I got a lot of, ‘Miss, why aren’t you striking? Don’t you believe what teachers are fighting for?’ I was like, ‘I do!’ I had a little bit of an internal struggle.”

After attending the big teachers union rally Monday at the Capitol, Cobb said she woke up Tuesday and decided to join her colleagues picketing, which she did for the strike’s duration.

The strike brought to the forefront just how different the two Beacon campuses are. At Grant Beacon, 80 percent of students qualify for subsidized lunch — slightly above the district average. That part of the city, like much of Denver, is gentrifying. The southwest Denver neighborhood around Kepner is not. The school is a safe harbor from violence and trauma.

About half of Grant Beacon students showed up for school during the strike, and six in 10 teachers joined the strike. Four miles and a world away at Kepner Beacon, 90 percent of students showed up for school — and all but a few teachers were out on strike.

Against the backdrop of the strike, Magaña said he emphasized that words matter. Everyone in the buildings, he thought, not just teachers, ought to be considered educators. That was the role everyone was thrust into — administrators, deans, and district central office staff who through no choice of their own had to cover for absent teachers. Magaña, too. He taught math.

“We maintained a positive culture through a really weird and complicated time,” said Tristan Connett, who as Kepner’s dean of students was pressed into service to teach eighth-grade reading and language arts. “Not just for students, but all the adults, everyone included.”

Outside Kepner Beacon each morning of the strike, teachers huddled over donuts and coffee. Parents brought them hand-warmers in the 20-degree chill. One teacher sat in her car with the engine running to record a video message to her students, telling them where she was and spelling out the day’s lesson plan before she joined the picket line, Cobb said.

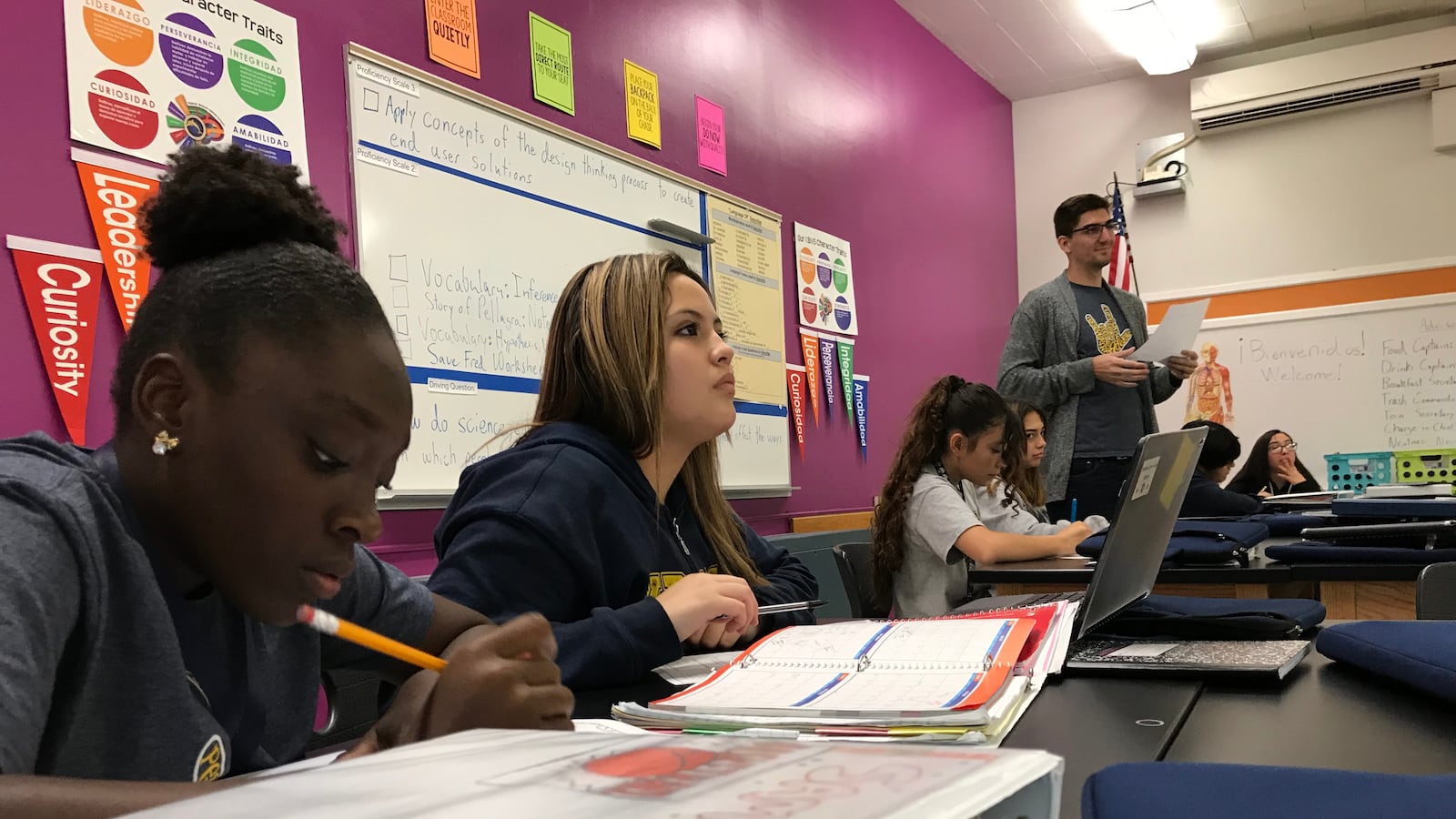

The Beacon schools promote character-building and use personalized learning, using data and technology to tailor instruction to individual students. As “innovation schools,” the schools are exempt from some state laws and aspects of the teachers union contract. Both schools were “green,” the second-highest ranking, in the district’s most recent school ratings.

Cracks in school culture did show during the strike. Magaña said one teacher at Grant Beacon was hurt by the negative reaction he received from striking colleagues.

The strike’s sudden end just after 6 a.m. Thursday led to mixed messages and confusion about what was expected of teachers that day, deepening rifts at the Beacon schools.

Cobb, the Kepner special education teacher, said teachers somehow got what turned out to be incorrect information from the union that they couldn’t be late for the start of school if they wanted to return.

Many striking teachers did not come back to school Thursday. That was out of step with the district as a whole, which saw more than 80 percent of teachers back in classrooms.

Some Beacon teachers, Magaña said, “said they were mentally and physically exhausted.” What, he asked, does that tell everyone who took on unfamiliar roles to keep the schools open?

When teachers, administrators, and staff arrived for Friday morning’s meeting, they congregated at tables with colored pencils and “reflection forms.” Everyone was asked to write down answers to two questions: What did you learn about yourself? What did you learn about your colleagues?

“I also brought out the obvious — the elephant in the room,” Magaña said. “There are hurt feelings. There is resentment from teachers to staff to students to parents. That is something we can’t pretend isn’t there, and we put it out there and acknowledge it to move forward.”

The message from the network administration left a number of teachers disappointed.

“Every teacher who went out on strike believed in it, we got this victory, and it wasn’t celebrated as a whole,” Cobb said. “It was more like there was an acknowledgement of what we want to repair. OK, but we felt like we deserved a little celebration for what we accomplished.”

Several teachers took up administrators’ offers to speak in private throughout the day, and when everyone gathered to wrap things up, Cobb said there was acknowledgement of what teachers had accomplished. Magaña said Saturday he doesn’t regret starting off the day like he did.

“We had to acknowledge all of the feelings of the group,” he said. “It was about all of us working together for a common ground.”

Under the tentative deal union members are expected to vote on next week, all of the teachers in the Beacon network will see their base pay increase. The incentives Kepner Beacon teachers receive for teaching in a “highest priority” school will be slightly smaller but will continue.

After the Presidents’ Day holiday Monday, teachers and students will return to school Tuesday for another test of the culture that has contributed to promising academic progress.

“It’s about trust,” Magaña said. “Some of it was cracked a little it. There was no contention in the room (Friday). It was really coming in with openness and willingness by everyone to say, ‘It’s done, and we did the right thing for ourselves. Now it’s time to come closer together.’”

“Normalcy will happen,” added Cobb, the teacher. “But it might take a bit.”

Correction: An earlier version of this story reported that Denver Public Schools were off Friday, when only some were.