At one school in the tiny district of Sheridan south of Denver, two social workers roam the hallways with handheld radios, responding to crisis after crisis.

It might be a student crying in class for unknown reasons, a disruptive student, or a fight. Less urgent requests, such as a check-in for a student who just seems to be having a rough day, usually come through email.

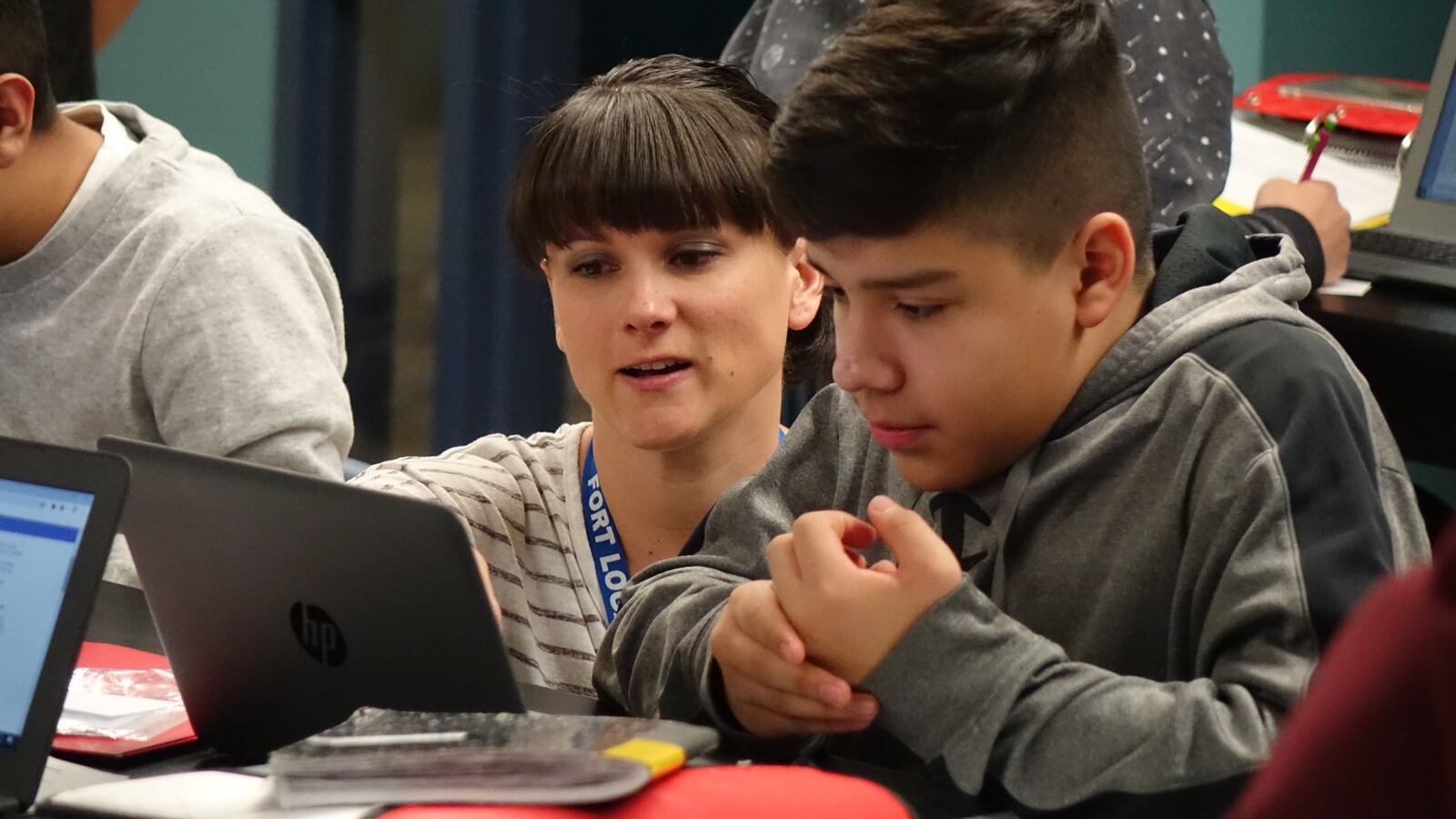

“It’s very much boots on the ground,” said Maggie Okoniewski, one of the social workers at Fort Logan Northgate.

The school has just under 600 students in grades third through eighth. The demographics are typical of the Sheridan school district. About one in four are identified as homeless — the highest rate for any school district in the state — and about 15 percent qualify as having special needs.

In between those calls, Okoniewski and her fellow social worker Danielle Watry check in on students they’ve identified as a priority. Every week the list includes about 60 students. In the last year, the list includes students from the heavily Hispanic population who have especially struggled with deportations or fears of separations, they said.

“And if I’m in the classroom, it’s almost certain that another student will flag us down,” Watry said.

Staff members say the resources that Principal Nelson Van Vranken has rolled out in the past three years are making a world of difference. That includes hiring Okoniewski and Watry. But it also includes two nearly full-time interns who help provide in-house counseling and therapy groups for students. The school also has a district-level school psychologist.

And just this year, Van Vranken hired a behavioral teacher who helps teachers work with students who have behavior problems such as lacking focus or blurting things out in class. In one-on-one sessions, she coaches them on skills to change their behavior. She also sits in class with students to help them apply the new skills. As a state and national conversation grows around ways to increase mental health supports in schools, staff at Fort Logan Northgate say the benefits are worth the investment.

Fewer students are slipping through the cracks, administrators, social workers, and teachers say. They also say culture is changing as students become more comfortable with each other and themselves. And teachers are staying longer, no longer overwhelmed by the challenges their students bring.

“I feel like I’m very supported here,” fourth-grade teacher Jessica Weissman said. When she has a student experiencing problems, “it’s very comforting to know if I have 25 other students to take care of, I know I can call someone and know this kid will be taken care of.”

Van Vranken said he saw the need to help teachers learn to work with students and give them more help, and he saw staff was more than willing. The district’s teachers union, seeing a high rate of trauma, had already been asking for more social workers and counselors in the schools.

“There’s a lot of needs in the community and, I would say, unaddressed mental health needs,” Van Vranken said. “Those were being put onto teachers in addition to the load they had. It was distracting them from being able to do the job they were hired to do.”

So he adjusted his budget to hire Watry. At the time Sheridan had just moved to give schools new control over their budgets, and Van Vranken decided his school would prioritize mental health. To hire the first social worker, he cut a counselor who was responsible for trying to address mental health need, while also providing academic advising.

The next year a grant helped him hire a second social worker. Each year, they’ve grown their team, this year bringing back a counselor, now through a state grant, who is now only responsible for academic advising.

That has contributed to lower teacher turnover. In 2015-16, only half of teachers returned to school the following year. In 2017-18 the school was able to retain more than three-quarters of its teachers — an improvement of more than 50 percent.

The National Association of Social Workers suggests one social worker per 250 students, or a lower number of students if students have “intensive needs.” Northgate’s two social workers don’t meet the recommended ratio, but with help from the interns and psychologist, the ratio is more closely aligned with recommendations. The union advocated at one point to setting required ratios in its district contract. That didn’t happen, but the district did add some supports. All Sheridan schools now have at least two mental health professionals.

Van Vranken said he had to get creative to secure additional resources like the school’s two full-time interns. The interns, through a partnership with Smith College in Massachusetts, receive credit toward their graduation requirements, but aren’t paid. Yet they provide a service, school-based counseling, that he saw a need for.

“When we came in assessing what the needs were, we saw we are in Arapahoe County, and on the western edge,” he said. “The services available to residents in Sheridan are very limited. They frequently have to drive a long way to get services, so for many of our parents who struggle financially, they’re simply not able to get themselves to services.”

As an added benefit, school officials say: As students become more used to seeing so many of their school classmates working with the mental health and social and emotional supports in their school, the stigma against addressing mental health is diminishing.

“We have students reporting so much more,” Okoniewski said. “Our ability to be so present has made the systems fall into place. Now when they do have stuff going on in school or other environments, it’s changed their view on what a mental health professional can help them with.”

Teachers also are learning from the mental health staff new ways to help students with more than academics and how to reinforce positive behavior.

Fourth-grade teacher Weissman, for instance, has students in her class start every day with deep breathing.

Students find a spot on the floor to focus on as they breathe. She said she can’t require them to close their eyes because some students don’t feel comfortable doing so. She tells the class that deep breathing can be a way to control their emotions in or outside of class.

Throughout the day, to help students focus she uses kinetic sand, positive reinforcements, and yoga breaks. Kids really like the tree pose, she said.

“I now see students self-regulating their emotions,” Weissman said. “And they’re so excited to tell me the different times they use the techniques they learned in here.”

Weissman and school staff believe it will later pay off in academic improvements too.

“You can’t learn if you’re struggling emotionally,” Weissman said. “You can’t ignore that they need that support. But the amount they’re now able to turn to me, the amount of times they’re now able to participate, they’re able to focus, their academics are going to improve.”

This story was updated to correct the spelling of teacher Jessica Weissman’s name.