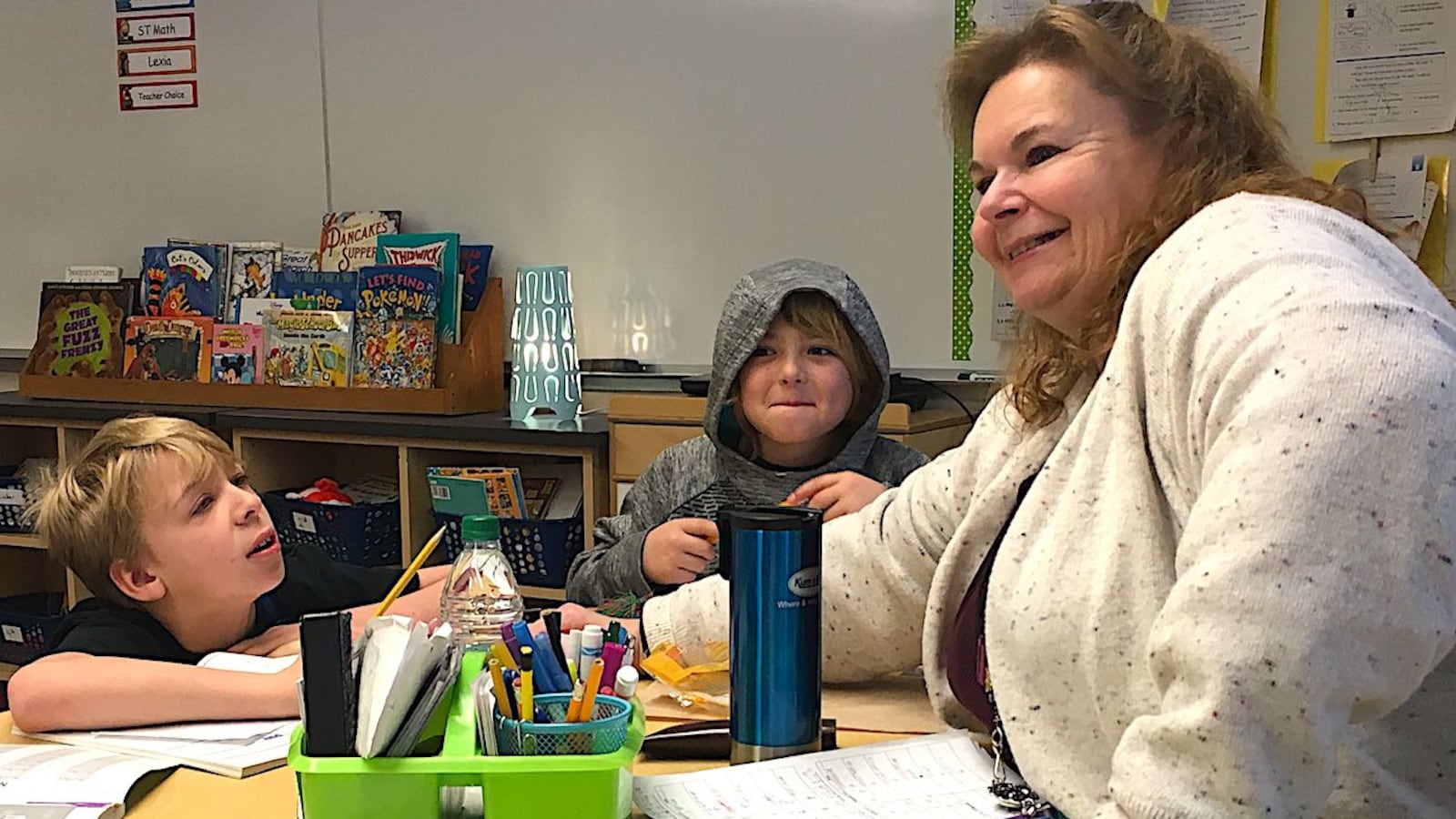

The fourth-grader sitting across the table from Wendy McSwain was not in the mood for learning. As his small-group reading lesson began, he meowed like a cat, asked McSwain to help him remember what “special” class he had that day, and talked excitedly with the fifth-grader next to him about the second Harry Potter book. When that classmate left to get a Band-Aid, the 10-year-old put a pencil in his mouth like a dog clamping down on a stick.

McSwain, a paraprofessional at Heiman Elementary School in the northern Colorado city of Evans, soldiered on with the lesson. She pointed to each letter printed in large font on a white laminated sheet — “i,” “k,” and “b” among them — prompting the boy each time, “What sound? Get ready.”

He answered correctly most of the time, except on “o,” which came out garbled because of the pencil.

Such antics don’t faze McSwain, a warm, even-keeled woman who students call “Miss Wendy.” She is one of 12 paraprofessionals at Heiman and among thousands across Colorado who work alongside teachers and therapists to educate students with disabilities.

In many ways, “paras” like McSwain, who earns just under $15 an hour, are the foot soldiers of the special education world. They do important one-on-one work with students amid the field’s constant hazards: burnout, turnover, staffing shortages, and funding constraints.

If these realities wear on McSwain, you can’t tell from her demeanor. She calls her charges “sweet pea” and “dude” and doles out high fives and Chex Mix between reading and math tutorials. She’s been on the job at Heiman, which houses two center-based programs for special education students, for over a decade.

Her long tenure is an anomaly in the field, including in her own district, the 22,500-student Greeley-Evans district. More than a third of paraprofessionals there leave their jobs each year, according to state data.

On average, paraprofessionals in Colorado earn $21,000 a year, less than half the average teacher salary. While the majority of them work with special education students, some fill other roles in schools, such as working with English learners or helping in large classes.

McSwain first became interested in special education as a teenager when she read “One Child” by Torey Hayden, a teacher’s account of working with a student with severe emotional problems.

“I was just like, I want to do that,” McSwain said.

She attended Metro State University for 2½ years, with plans to major in elementary education, but left early to start a family. When her two sons, now 18 and 22, were young, she ran an in-home daycare. She started as a para at Heiman the year her youngest entered first grade there.

In Colorado, paraprofessionals are required to have an associate degree, two years of college credit, or simply to have passed a special exam. In contrast, licensed teachers must have a bachelor’s degree or higher.

Ritu Chopra, executive director of the PARAprofessional Resource and Research Center at the University of Colorado Denver, said one of the biggest issues in the broader special education field is paraprofessionals’ lack of training and the fact that they are inadequately supervised by licensed teachers.

She said federal and state laws are lax on those fronts, leaving individual school districts with significant leeway in how they use and oversee paras.

“They are very important members of the team, but they are not teachers,” Chopra said. Too often, “Paras are being given too much responsibility beyond the scope of their legal and ethical role.”

Heiman Principal Anne Ramirez said she agreed with Chopra’s critique on para training and supervision. Several of her own paras have asked for more training opportunities in their end-of-year evaluations, she said.

Even with some useful recent changes — the hiring of a school dean who checks in with paras regularly and a district decision to pay paras to attend five training days a year — more is needed, Ramirez said.

For someone like McSwain, a seasoned veteran who’s taken just about every training offered, there’s little to choose from, she said.

McSwain began a recent day in a fourth-grade classroom, sitting next to a student who attends one of her math pull-out groups. After the Pledge of Allegiance and a quick discussion about a schoolwide campaign to stop using the “R-word” — retarded — she and the boy headed off to the special education room where she spends much of her day. They picked up a few other boys along the way.

At a table tucked behind a portable accordion partition, McSwain worked with rotating groups of two to five students. At times, she used scripted lessons from curriculum guides and other times, she helped students solve problems in their workbooks.

McSwain’s students all have at least two types of disabilities, the most common being learning delays, emotional impairments, and autism. Still, they spend at least 70 percent of their time in general education classrooms, coming to see Miss Wendy for a half hour here or 40 minutes there.

During pull-out groups, McSwain is a multi-tasking wizard. She uses a pink pen and a name chart to keep track of how many turns each child gets to answer questions, whether they’re answering correctly, which words or math problems are stumping them, and who’s earned play money for good behavior. All this while refereeing “he-poked-me” squabbles and other disruptions.

Ramirez praised McSwain’s kindness, consistency, and her ability to keep outside distractions at bay.

“The kids know what they’re going to get every day from her,” she said.

Some of McSwain’s students are far behind academically. The fourth-grader with the pencil in his mouth and his fifth-grade tablemate were both practicing kindergarten-level reading skills, sounding out simple words like “big” and “but” — a sequence that caused much giggling.

McSwain admits her job takes a lot of patience, but said she likes helping kids learn and seeing their “aha” moments. And when her internal frustration level rises, there’s always the chocolate stash in the staff cupboard.

Besides the last day of school, when McSwain gets teary as her fifth-graders depart for good, her least favorite part of the job is restraining students who are out of control.

She’s taken a training on how to do it safely, but said, “That’s not who I am. I’d rather love you and give you a hug.”

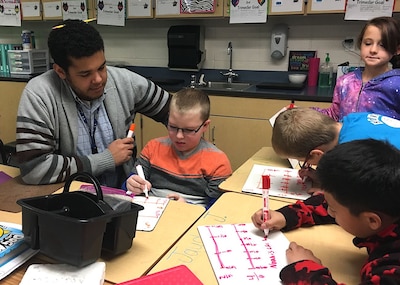

Some paras at Heiman spend most of their time in general-education classrooms, helping ensure that special education students keep up with the class. Jordan Dixon, who used to lead an educational program on an organic farm in California, is one of them. On a recent day, he worked most intensely with two third-grade boys who struggle with emotions, but during a whole-class game of math Jeopardy he stopped to help other third-graders as well.

Like many paras, Dixon plans eventually to become a licensed teacher. He already has a college degree in agricultural communications, so will enroll in an alternative certification program to complete the rest of his requirements.

Chopra calls paras an “amazing pool” of future teachers, especially since they often reflect the racial, cultural and language backgrounds of the students with whom they work. Next year, Heiman will lose three paras who are leaving to pursue teaching degrees, Ramirez said.

Because McSwain spends a lot of time with the 14 or so students who attend her small groups, she gets to know some of them quite well. One blond-haired boy, still wearing snow pants from the frigid trip to school, admitted as much during his morning reading session.

“Miss Wendy knows everything about my life,” he said, “cause I tell her everything.”

A few minutes earlier, the fifth-grader, who’d been working on a third-grade reading passage, had offered a grim assessment.

“I can’t read,” he said.

She corrected him: “You can read. I’ve seen you do it. You’ve just read this whole page.”

The boy pushed back. Fifth-grade books were still too hard for him, he said.

“We’re working on that,” she said. “We’re helping you get there.”

McSwain is also quick with a pep talk for students going through rough times at home.

As she walked a fourth-grade boy back to his main classroom, she mentioned seeing his mother at the drugstore where she worked.

“She’s trying to get back on days for you, so she can be there when you get off the bus,” she said.

As they parted, she wished him an “awesome possum day.”