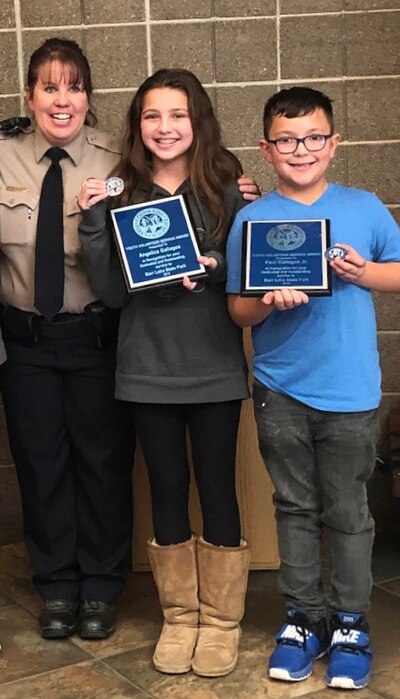

While many children across Colorado are heading to school on Monday mornings, siblings Angelica and Paul Gallegos of Brighton are on their way to Barr Lake State Park’s Nature Center to volunteer.

“Every time we go, we all learn something different, something new, and I just think it’s awesome that I’m able to give my kids an opportunity to go out and learn something, try something outside,” said their mother, Crystal Gallegos.

Angelica, 13, and Paul, 9, have been volunteering once a week at the state park since last August, when the Brighton-based District 27J transitioned to a four-day school week.

As more Colorado school districts cut back to just four days a week in the face of financial pressures, many parents are looking for ways to fill that fifth day — they hope with meaningful learning outside the classroom. Organizations like Boys and Girls Clubs have stepped in to fill the gap, and so have new nonprofits and business partnerships that provide everything from workplace learning to gardening and robotics classes.

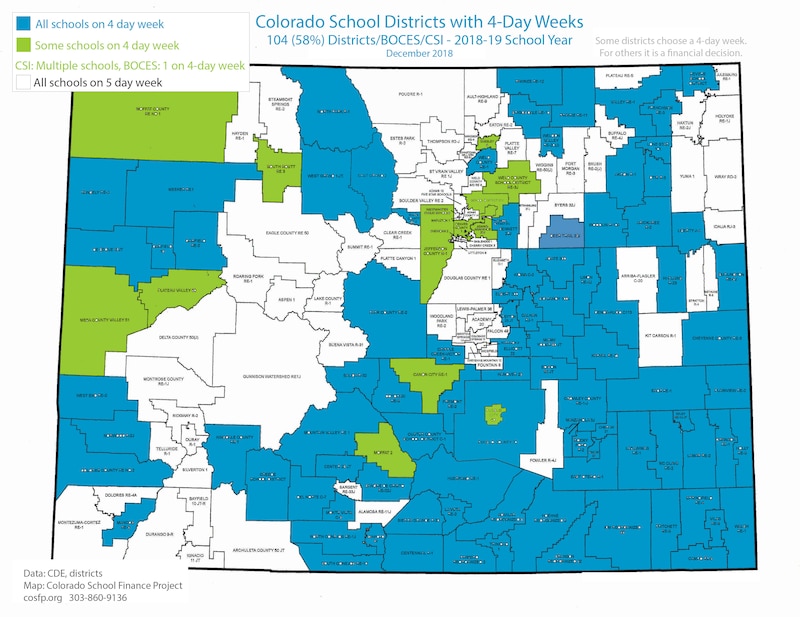

This school year, state data shows 104 of Colorado’s 178 school districts — serving more than 80,000 students — operated on four-day weeks, up from just 39 in 2000. In fact, Colorado has the highest proportion of school districts operating on four-day weeks in the country, according to the National Conference of State Legislatures.

In many communities, parents and teachers have come to embrace the schedule. The free weekday gives rural families a chance to go to the dentist or the doctor, which could be up to three hours away. Older rural students may work at ski resorts and other local businesses. And student athletes might not have to miss school to travel to away games.

But four-day weeks exact some costs. A study that looked at nearly two decades of Colorado crime data found that youth crime rates spike in four-day districts.

Supporters say the four-day school week opens up educational opportunities for students, and the Colorado Department of Education backs some of these efforts with grants.

For example, in Kremmling, the Colorado AeroLab has created weekly programs for students attending North Park R1, South Routt County RE3 and West Grand 1JT school districts, who are out of school on Fridays. The programs are free to students through a 21st Century Community Learning Centers grant from the state education department. These grants fund after-school and other extracurricular programs, some to support activities in four-day districts.

Program Director Elaine Menardi said the organization strives to offer educational opportunities not available at school, in disciplines such as agriculture, entrepreneurship, architecture design, construction and robotics. The group also provides activities like interactive puzzle and logic games for children.

“The potential is in academic enrichment, helping kids to learn in different ways,” Menardi said.

At the same time, relying on non-profits to provide education raises questions about equity. Unlike schools, the doors aren’t open in all districts or to all families.

Antonio Parés with the Donnell-Kay Foundation has studied the issue of four-day weeks for years. (Donnell-Kay is a financial supporter of Chalkbeat.) He believes lawmakers could consider creating stronger incentives to motivate school districts to involve all students in learning experiences five days a week.

Because Colorado is a local-control state, where the state cannot mandate school districts to operate in certain ways, Parés said it may be easier for legislators to offer more money to school districts with four-day weeks if they agree to go back to five days a week of learning, even if the fifth day is something outside of the traditional classroom setting, like if the district partners with other nonprofits, for example.

“A lot of these districts, there’s so many things unique to them, being rural, based on their industry, based on whatever, so let’s incentivize them to have kids… learning in some way or another Monday through Friday that best suits their needs,” Parés said.

He believes voters might be willing to fund those programs, as long as they have a clear idea of where the money will go and what it will do.

Parés also suggested that Colorado could, with voter permission, create tax credit programs to send more money to nonprofits that serve students on the fifth day.

Having those incentives could help solve the need for child care many parents still have on the fifth day, especially in more urban districts like Brighton, which has more than 5,000 at-risk students, according to state data.

Gallegos said she knows of Brighton parents who do a “kid share” to make ends meet. Parents take turns taking off on a Monday to watch everyone else’s children while the other parents go to work.

“I know there’s a lot of parents out there who struggled, and still struggle, in trying to get child care for their kids on Monday,” Gallegos said. “I’m lucky enough to have an employer that lets me work from home on Mondays. Otherwise, I have no idea what we would do.”