In 2016, amid pervasive worries about data privacy and governmental intrusion, the State Board of Education put the brakes on a proposal for a detailed public report showing whether Colorado kindergarteners are ready for school.

In a move counter to its own staff recommendation, the board opted for a slim summary containing little of the information schools collect on their kindergarteners, and none on district-by-district differences.

For those who want to invest in young children, the board’s March 2016 decision led to a data dead end, sweeping a rich source of information about Colorado’s early childhood landscape under the rug. With hundreds of millions in public and private dollars devoted to early childhood programs each year, they say the dearth of data makes it harder to figure out whether these investments are paying off or falling short.

But lately there’s growing momentum to change the state’s kindergarten readiness reporting system. It could happen through a new state board vote, legislation, or some other means. Colorado’s Early Childhood Leadership Commission is studying the issue and could make a recommendation later this year.

Gov. Jared Polis, who successfully pushed for free statewide full-day kindergarten and pledged to expand state-funded preschool to all 4-year-olds, said through a spokesman that his office will work with state education officials, lawmakers, parents and advocates “to ensure we have a more holistic picture of kindergarten readiness.”

Until then, the people around the state who want to improve educational outcomes for children, especially those with the greatest needs, have to find other ways to get data they need — or simply do without.

“It’s a missed opportunity,” said Jennifer Stedron, executive director of the nonprofit Early Milestones Colorado, “not to be able to use that information so we can do a better job with our dollars.”

Susan Steele, who heads the Denver-based Buell Foundation and is a member of Colorado’s Early Childhood Leadership Commission, said the state’s kindergarten readiness report is too vague to help her organization or the broader early childhood community. (The Buell Foundation is a funder of Chalkbeat.)

For example, the report doesn’t detail the percentage of kindergartners who met readiness standards in each of the six assessment categories, literacy, language and comprehension, social and emotional development, cognition, and physical well-being and motor development.

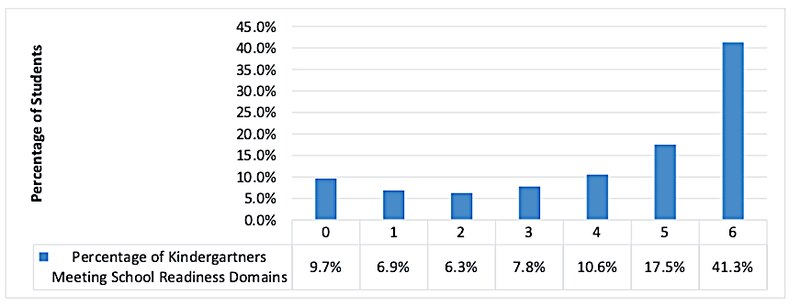

Instead, the report only indicates how many readiness standards Colorado children met. But with only 41% of Colorado’s kindergarteners meeting all six developmental milestones according to the 2019 report, that means more than half of Colorado’s kindergartners are falling short somewhere. The problem is it’s hard to tell exactly where.

Steele said the current reporting system means philanthropists, voters, and policy-makers who want to make strategic investments in early childhood programs are stuck with minimal information until the next big data milepost in third grade.

“That’s a long time without a detailed baseline,” Steele said. “You’ve lost a huge developmental period for kids.”

How did we get here?

In 2008, Colorado lawmakers passed a major school reform law known as CAP4K, which aimed to align preschool through postsecondary education. Among its many provisions, it mandated that schools assess kindergarteners soon after they arrive in the classroom and that the state report out those results.

But it left the details for the State Board of Education to decide. When that finally happened eight years later, the board debate reflected statewide concerns about data privacy, with members of the Republican majority most vocal.

“Timing is a piece of the puzzle here,” said Bill Jaeger, vice president of early childhood and policy initiatives at the Colorado Children’s Campaign. “The pendulum swung so far around the issue of privacy.”

In the last few years, a raft of education and advocacy organizations have begun to push back against stringent data privacy rules they say have chipped away at transparency.

For months in late 2015 and early 2016, debate among state board members ranged widely as they discussed what kind of kindergarten readiness reporting system to adopt. Some board members balked at the idea of having school districts report student-level results to the state and having education department staff compile an aggregate version. They worried it was intrusive, feared that a poor showing in kindergarten could pigeonhole children for years, and said CAP4K didn’t explicitly require it.

Deb Scheffel, one of the most vocal supporters of a bare-bones report, questioned the value of using data to steer improvement.

“To say that shining a flashlight on this is going to create gains hasn’t been a great strategy in the past,” she said, according to a transcription of the Feb. 10, 2016, board meeting. “We have the longest longitudinal database, one of the longest and most robust in the nation. And just having that database has not resulted in raising student achievement.”

Scheffel declined two interview requests from Chalkbeat.

On March 9, 2016, six board members, including Scheffel, Val Flores, Jane Goff, Steve Durham, Joyce Rankin, and Pam Mazanak, voted in favor of a limited kindergarten readiness report. Angelika Schroeder, who had argued consistently for a more detailed report, voted no.

Individual school districts have access to kindergarten readiness data for their own students and have used it to inform local decisions.

For example, when administrators in the Boulder Valley district found that kindergarteners were coming in low on early math concepts, they beefed up teacher training on the subject.

Kim Bloemen, the district’s executive director of early childhood education, said literacy and social and emotional skills had been a main focus previously.

Now, she said, “We’ve taken a shift and we’re going to do lots of math professional development.”

It’s the kind of work some early childhood leaders say should be undertaken on a regional or statewide scale in kindergarten and even earlier.

Mat Aubuchon, director of elementary education for the Westminster district north of Denver, said the state’s readiness report “doesn’t help us much” in part because it’s impossible to know how district kindergarteners are doing compared with those elsewhere, and whether local trends match statewide patterns.

Are kids thriving?

Gauging whether kindergarteners have met key developmental milestones early in the school year isn’t unique to Colorado. About half of states require schools to administer such assessments, according to a 2018 Education Commission of the States report.

In Colorado, most schools use an observation-based tool called Teaching Strategies Gold, which evaluates young children on everything from controlling strong emotions to recognizing letter sounds to understanding shapes.

The idea is to help teachers and parents understand students’ strengths and weaknesses and inform individual learning plans required by CAP4K. In most states, including Colorado, assessment results aren’t meant to block kids who haven’t hit expected milestones from entering kindergarten.

While states vary widely in how and to whom they report kindergarten readiness results, the CAP4K law called for a big-picture reporting system that allows the state to track population-level changes in students’ skills and knowledge.

What emerged after the state board decision was a six-page brief that is far more abridged than other Colorado test results, including the one tracking the state’s publicly funded preschoolers.

It includes a chart showing the percentage of kindergarteners who hit the “readiness” mark in all six developmental categories, five of six developmental categories, four of six, and so on. It doesn’t specify which categories students are hitting or missing. There are additional charts with the same format, disaggregated by student demographics.

In contrast, a report on the READ Act, a 2012 law mandating reading assessments for all K-3 students and extra help for those who struggle, runs 38 pages and includes district-by-district results. The public has access to reams of school and district state test results from third grade on.

Stedron, of Early Milestones Colorado, said the public would never be satisfied with state test results that didn’t distinguish between math and literacy in higher grades, but that’s essentially what’s in place for kindergarteners.

“I would encourage everyone to look at what the intent of CAP4K was and whether the way that reporting is happening for kindergarten … is meeting the intent of CAP4K,” she said.

Below is the state’s six-page summary of kindergarten readiness in Colorado, excerpted from the 2019 CAP4K report.