The state’s largest teachers union and organizations that represent school boards and district leaders are mounting a united front against proposed changes to how Colorado rates its schools — even as education advocates say the current system leaves parents in the dark.

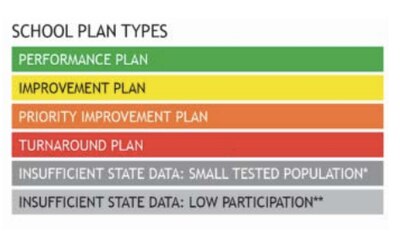

At issue is what’s known as the school performance framework, a measure of school quality that is largely based on standardized tests students take in the spring. The Colorado Department of Education assigns schools one of four ratings — performance, improvement, priority improvement, and turnaround — and schools with one of the two lowest ratings go on a state watchlist. Those that don’t improve after five years can face state intervention, which can range from state review of improvement plans up to school closure.

These ratings rely more on growth, a measure of how much progress students make compared with their peers, than pure achievement on state tests. That means that 72% of schools hold a rating of “performance” even as a majority of Colorado students don’t read, write or do math at grade level.

Concerned with this discrepancy, the State Board of Education has been debating for months a series of changes to how it rates schools, including:

- Adding an “on-track” metric that looks at how long it would take students to reach the next performance level at their current rate of growth,

- Raising the bar for schools to earn the highest rating, a change that would leave many more schools in the “improvement” category,

- Adding a new “distinguished” rating for the top 10% of Colorado schools.

The State Board of Education is once again taking up this issue Thursday. The board needs to make a decision by November for these changes to be applied to the school ratings issued in 2021.

Including some sort of on-track metric is required by law, and that change is the least controversial. But the possibility of making it harder to earn a “performance” rating or adding a “distinguished” category has generated substantial pushback.

The Colorado Education Association, the Colorado Association of School Boards, and the Colorado Association of School Executives issued a joint press release calling on the State Board not to adopt any of the proposed scenarios and instead enter into “collaborative discussion” to reconsider the current accountability system.

“It is the view of superintendents from districts rural and urban, large and small, affluent and poor that the proposed changes to the accountability system will only add to the existing confusion about the purpose of the frameworks, the validity and reliability of the data and will fail in the goal we all share of increasing student learning,” more than 140 superintendents and heads of rural education cooperatives wrote in a letter to State Education Commissioner Katy Anthes.

“Each of the scenarios shared still relies heavily on high-stakes standardized tests to determine school quality, despite the abundance of research that has shown that high stakes tests fail to fully capture the true quality of education provided in a school,” wrote Amie Baca-Oehlert, president of the Colorado Education Association, the 38,000-member teachers union. “These labels often lead to harmful consequences such as high staff turnover, driving families away from their neighborhood school, while also sending a negative message to students that they are failing.”

The Association of Colorado Education Evaluators, an organization representing people who work on assessments, also came out against most of the proposed changes. In a letter to state officials, organization members were particularly critical of the “distinguished” category and noted the strong correlation between a whiter, more affluent student body and higher test performance, which in turn leads to higher ratings.

“Education stakeholders are left to wonder whether the state is attempting to recognize schools that have high achieving students or schools having the ability to curate an advantaged population,” the letter says.

According to an analysis prepared by the state Education Department, in schools that earn the state’s lowest rating, an average of 78% of students live in poverty and 27% are English language learners. In contrast, just 35% of students at high-performing schools live in poverty and just 14% are learning English.

Scenarios that would raise the bar to earn the highest rating increase these disparities. That is, as it gets harder to earn the top rating, the schools that receive it have fewer students in poverty or learning English.

If the “distinguished” category were introduced, the schools that would qualify would have, on average, just 16% of their students in poverty and just 7% learning English.

Part of this debate turns on the purpose of the ratings. The state uses them to identify schools that need the most help, provide them with additional resources, and move for greater intervention if things don’t improve. Schools that dip from “performance” to “improvement” take a hit to their reputation but receive no additional resources.

But for many education advocates, this is important information that the public — and parents — deserve to know.

In a letter, education advocacy group A Plus Colorado said the ratings must “signal something about the school’s success in supporting students to learn.” By giving so many schools a rating of “performance,” the current system falls short and needs to change.

Read more: Raising the bar or moving the goalposts? Changes pending for Colorado school rating system

“We believe that the accountability system sets public expectations of the academic outcomes our students deserve and communicates whether schools and districts are supporting students to reach those academic outcomes,” the organization wrote.

On Twitter, the conservative education reform group Ready Colorado lambasted the teachers union and school district organizations as the “Three Musketeers of the status quo” and said the current system amounts to giving “participation trophies” to schools that aren’t serving students.

“We reject the notion implicit in their argument that demographics determine a child’s destiny,” Ready Colorado President Luke Ragland wrote in an email to Chalkbeat. “Colorado has schools that are beating the odds for children of color and low-income students, and they should be recognized for their excellence. The state should be raising expectations for all schools and all kids. The status quo is trying to pull the wool over the public’s eyes.”

Correction: This story has been changed to reflect that if the State Board adopts a new policy by November, it will affect ratings issued in 2021, not 2020.