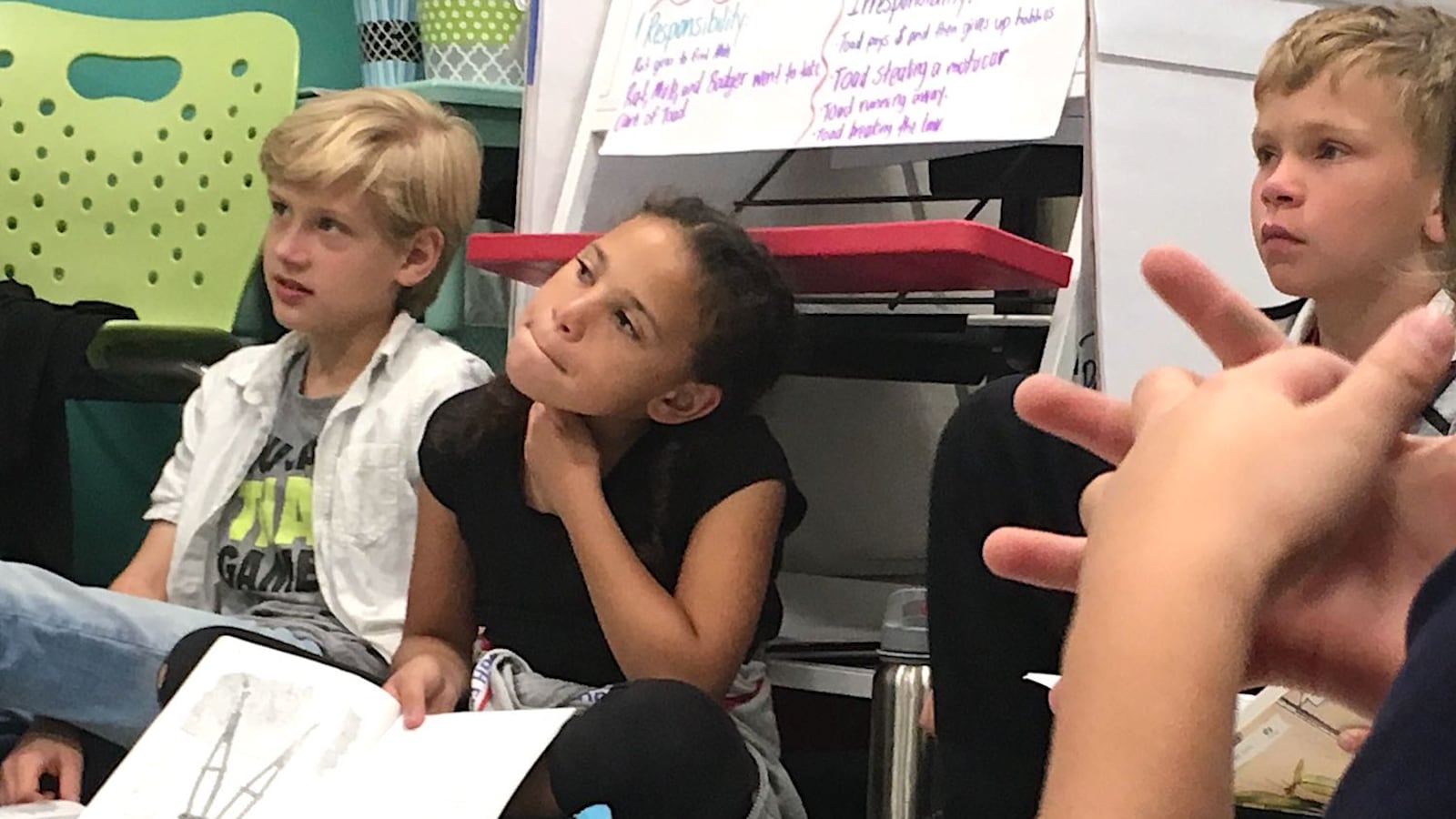

Tammy Kennington and the four children in her cozy therapy room prepared to sound out the word “April.”

“Divide before your first medial consonant. Accent the first syllable,” Kennington said, her fourth graders quietly echoing her words.

“A vowel in an open-accented syllable is long. Code it with a macron,” they said. “A vowel in a closed syllable is short, code it with a breve.”

Methodically, Kennington and her students narrated each step of the decoding process as the children penciled in slashes, accents, circles, or stress marks on all 13 words in the sentence. Three minutes and 20 seconds later, they put it all together: “For her birthday in April, we gave her a blue and white apron.”

This is what learning to read looks like for the 122 second- through fifth-graders who attend the Academy for Literacy, Learning & Innovation Excellence in Colorado Springs. Run by School District 49 and commonly referred to as ALLIES, it’s the state’s only public school for students with dyslexia. Private schools with the same mission can run $30,000 annually.

ALLIES, now in its third year, is ascending at a time when lawmakers and education leaders are raising big questions about why so many Colorado children can’t read well and what the state is doing to remedy the problem. There’s also been a growing push among parents and other advocates to better serve students with dyslexia, a learning disability that can make reading, spelling, and pronouncing words difficult.

Recent activism helped spur a new state law that called for a pilot program for dyslexia screening and a work group charged with recommending policies to support students with dyslexia. In addition, advocates around the state plan to open additional public schools for students with dyslexia over the next couple years. A K-8 school in El Paso County and a K-4 charter school in Fort Collins are set to open next fall. A Jefferson County mother is working on opening a similar school for sixth- through 12th-graders in 2021.

Lynne Fitzhugh, president of the Colorado Literacy and Learning Center in Colorado Springs, attributes growing awareness about dyslexia partly to parents “tired of their children falling through the cracks.”

Experts estimate that dyslexia affects 10% to 20% of the population. In Colorado, that’s 90,000 to 180,000 schoolchildren — far more than the 41,000 students officially designated as having a “specific learning disability,” an umbrella category that includes dyslexia.

“There could be an ALLIES in every district in the state and it wouldn’t be too much,” said Fitzhugh, one of the leaders of the new K-8 school for students with dyslexia.

Desperation

Jocelyn Conrad, a teacher herself, knew something was wrong when her daughter Genevieve was in first grade. The little girl struggled constantly with reading — even simple sight words like “the.” She would recognize it in one sentence and have no idea what it was a sentence later. Sometimes, she’d be able to read words one day but couldn’t the next.

“She used to beat her head against the table because she couldn’t read,” said Conrad, tearing up as she described the experience. “She used to say, ‘I hate my life,’ She was 7 when she would say this.”

It’s a familiar story to ALLIES Principal Rebecca Thompson, who fields calls all year long from worried parents, usually mothers.

“They’re crying and they’re heartbroken, and they just don’t know what else to do,” she said.

The seeds of ALLIES were planted about a dozen years ago when Thompson was an assistant principal at District 49’s Odyssey Elementary. A mother stopped in and told school leaders her son needed a special program for students with dyslexia, but Thompson and the school principal realized they knew little about the disability or effective interventions.

After investigating the program the mother mentioned, they tried adopting it on a schoolwide basis. But it was designed for one-on-one instruction, not large groups, so didn’t work well. For the next few years, Thompson continued searching for answers, coordinating staff training on dyslexia, and taking classes herself on dyslexia screening.

In 2014, Thompson and the team at Odyssey launched the “Lex Program,” which provided daily therapy, smaller class sizes, and specially trained teachers for second- through fifth-graders who had characteristics of dyslexia.

In 2017, that program became ALLIES, a separate school housed in portable classrooms on the Odyssey campus. This year, ALLIES moved into its own building on that campus — a small but shiny school peppered with motivational messages such as “Let the journey begin,” and “Spread your wings and fly.”

Oasis in a desert

ALLIES, which sits in a quiet residential neighborhood in northeast Colorado Springs, serves students from District 49 and six nearby school districts. One family drives an hour each way so their child can attend. Others have moved to the area from out of state to be near the school.

Throughout the school’s short history, Thompson has led countless tours for superintendents, special education directors, teachers, and parents who want to learn more about the ALLIES model.

There are lots of people who want to do something for students with dyslexia, she said, “they just don’t know how to tackle it yet and I think we’re right on the cusp of that.”

ALLIES wasn’t open yet when Conrad began to realize the extent of her daughter’s reading struggles.

She hired a tutor to help Genevieve during first grade and that spring brought her daughter to a Denver psychologist to get her tested for dyslexia. The results not only showed Genevieve had dyslexia, but that she was so anxious about reading, she could have been given an anxiety disorder diagnosis as well. Conrad said her family dipped into savings to pay the $2,400 testing bill.

Genevieve repeated first grade in her home school outside of District 49, but still wasn’t making much progress. That’s when Conrad visited ALLIES on the advice of a friend. There, she saw the setting she dreamed of for Genevieve.

“I need my kid to be here,” she remembers thinking.

Genevieve, now a third-grader, started at ALLIES last year. Lately, she’s taking a stab at reading chapter books, something that would have been unthinkable previously.

Conrad also likes that Genevieve gets to work on projects that play to her creative strengths in the school’s “Innovation Lab.” There, the 9-year-old recently constructed three-dimensional barns, complete with swinging doors and latches.

At ALLIES, Genevieve is finally happy.

“It saved her,” Conrad said. “I didn’t even know where she would be if she wasn’t there.”

ALLIES also led to a pivotal moment in Conrad’s own career, prompting her to leave the El Paso County district where she’d taught for years to teach sixth-grade language arts in District 49.

Her rationale was simple: “Here’s this district that gets it, and I want to be a part of it.”

Critical ingredient

One of the hallmarks of ALLIES is its daily 50-minute therapy block. Certified academic language therapists work with just four students each using “Take Flight,” a curriculum developed by Texas Scottish Rite Hospital for Children and based on the well-known Orton-Gillingham Approach to teaching reading.

To outsiders, Take Flight sessions can sound like a foreign language, with their references to words like digraph — a two-letter combination that represents a single sound — and tittle — a dot placed over an “a” or “g” to remind students of their pronunciation in certain contexts. But for students who can’t learn to read with traditional classroom instruction, it’s a way into the mysterious world of written language.

“We’re teaching them the rules of the game,” said Teresa Hinote, the lead Take Flight therapist at ALLIES, and a former staff member at Scottish Rite Hospital. “It is so systematic and so structured and so explicit.”

On a recent morning, a fourth-grader named Faith looked at a Winnie the Pooh picture book while she waited for Take Flight therapy. Asked what kinds of words are hard for her, she pointed to the word “afternoon” in her book.

“I can say ‘the’ and ‘will’ and ‘no.’ Those are easy,” she said. “It’s like big words. I can’t, kind of, say them.”

Take Flight therapy, which lasts for three years at ALLIES, is such a critical part of the school day that staff take pains never to schedule assemblies or special events during therapy blocks. They also don’t allow students to enroll in ALLIES mid-year because they’d never catch up on Take Flight lessons.

While reading scores often plateau or even dip after the first year of Take Flight, they jump dramatically by the end of year two, according to district data.

“We have taken a child all the way back to the beginning, and they have to relearn everything,” Thompson said.

ALLIES is not the only public school in Colorado to provide Take Flight therapy, but others don’t typically offer it with the same intensity or frequency, she said.

A pricey model

Unlike students at most elementary schools, those at ALLIES switch classes every 50 minutes, and most classes are limited to 12 students. Teachers — called professors at ALLIES — are all trained in how to work with students who have dyslexia, as well as other co-occuring conditions such as attention deficit hyperactivity disorder, a writing disability called dysgraphia, and a math learning disability called dyscalculia.

Besides Take Flight, students take math, language arts, a class devoted to online math or reading practice, and another that combines art, music and physical education. They also attend Innovation Lab, which incorporates science and social studies in a makerspace atmosphere.

While all ALLIES students have been screened for dyslexia and show telltale signs, many don’t have an official diagnosis. That’s because formal evaluations are costly and time-consuming — putting them out of reach for many families.

Jessica Cook, whose third-grader Isabella attends ALLIES, said she considered getting her daughter tested after the girl’s former teacher recommended ALLIES. But the $1,500 price tag was impossible on Cook’s medical assistant salary.

About a quarter of ALLIES students qualify for special education services and another 7% have what are called “504 Plans,” which require certain accommodations for students with disabilities. In practice, however, all ALLIES students get specialized instruction and accommodations.

Cook knew that Isabella had long struggled with reading — along with attention deficit hyperactivity disorder. Classmates at her former elementary school called her “baby” because she couldn’t understand the stories they read in class. At least once a week she broke down in tears after school, and sometimes she begged her mom to home-school her.

Cook, who lives a few minutes away from ALLIES, was shocked when she discovered everything the school provides — iPads for every student, small group therapy sessions, and gleaming whiteboard tables to name a few features.

She remembers her reaction: “This is insane. Are you sure this is not going to cost any kind of tuition whatsoever?”

The answer was no, but that doesn’t mean ALLIES is cheap. While most other elementary schools in District 49 spend around $6,000 to $7,000 per student, ALLIES spends a little over $10,000 per student, according to the district’s latest budget.

Michael Pickering, leader of the seven-school zone in District 49 that includes ALLIES and CEO of the Colorado Literacy and Learning Center, said students’ huge reading gains in the Lex program laid the groundwork for ALLIES.

And while it was nerve wracking at times to fold dyslexia interventions commonly found in private practice into a public school, he said, district officials wanted “to be able to offer something that students typically wouldn’t be able to access because of cost.”

At $60 an hour, private Take Flight therapy would be unattainable for most families, he said.

Pickering, who is also involved in the planned K-8 school for students with dyslexia, said stand-alone schools like ALLIES provide valuable learning labs for educators to see effective interventions for dyslexia — particularly when the concept of school-based dyslexia therapy is new.

But over the long run he doesn’t believe such schools are a must-have in every Colorado district. Instead, he’d support a certified academic language therapist in every school along with training for all teachers on how to support students with dyslexia.

If that comes to pass, Pickering said, “Oh my word, we would have a vastly different landscape for students with dyslexia across Colorado.”