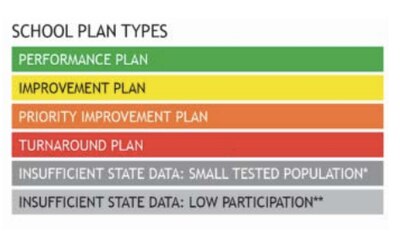

Two years of making small improvements, even without producing dramatic results, could be enough to enable Aurora Central High School to fend off deeper involvement of state officials this week.

The high school, trying to meet a state deadline for improvement, must show why it deserves more time to boost student achievement.

The school wrote its innovation plan — which gave it freedom from parts of its union contract, district rules, and state laws around hiring, budgeting, and curriculum — in 2016.

The next year the State Board of Education gave the school two years to improve. It has succeeded in cutting teacher turnover and improving graduation rates. But Aurora Central’s state rating has stayed low, and the school earned fewer points in the state rating system than last year.

This week, the State Board must decide whether to change its improvement orders or allow the school to keep trying. If it were to choose a different direction, the board would be limited by law to certain options, such as closing the school, ordering an external company to take over, or turning the school into a charter school.

Aurora district officials will argue that Aurora Central has been showing improvements in its culture through improved student behavior, attendance, as well as parent and teacher satisfaction, as shown on surveys, and that the improvements in academic achievement will follow in time.

A state review panel of outside experts agrees that is the best path forward. It notes small improvements and agrees the past few years required setting the foundation to improve school culture. Now the real work begins, it says.

The 1,900-student high school sits in a historical and diverse area of the city near 11th Avenue and Peoria Street. About 45% of the school’s students are English language learners. About two-thirds of all students qualify for subsidized lunches, a measure of poverty.

School and district officials boast that the school has improved its graduation rate to about 70%, up more than 25 percentage points from 2014-15. But over the last five years, Aurora Central has lost the most students in the district to other schools outside Aurora, and to dropouts.

Teacher turnover has improved. It was only 18.42% last school year, down from a high of 52% in 2015-16. The school also started this school year with 100% of its jobs filled — a first, at least in recent times.

But teachers who are now staying at Aurora Central are, on average, newer teachers. That’s why one of the biggest keys to improving Aurora Central involves teacher planning.

The school, exercising its budgeting flexibility, has hired a coordinator who oversees professional learning communities — that’s the name for the groups of teachers that meet to plan together. This coordinator has started coaching teachers to facilitate their own meetings.

Because there are so many teacher planning groups, and not enough instructional coaches to lead each one, a consultant, Mass Insight, helps coach teachers to become planning facilitators.

“I do believe that is the key to teacher retention,” said Gerardo de la Garza, who is in his fourth year as principal of Aurora Central. “Providing a structure for those folks to come together and learn together, you provide that opportunity to build that capacity — to in a sense become leaders.”

One report from a third-party review found that Aurora Central’s teaching and teacher planning have improved, but found that teachers are still not using enough strategies to educate English language learners, particularly outside of literacy classrooms.

De la Garza said that this year, he is now focusing more on improving instruction. He said teachers are digging into state standards, and working together to track how students are doing.

The third-party review notes that instruction has improved and moved away from lectures to more student activities that engage students, but also found that teachers are still not always providing enough rigor.

And while student attendance has improved over several years, chronic absenteeism started to rise again last year. The problem spilled out on television news when neighbors called police to report students roaming the neighborhood littering and fighting.

But school and district officials point out that more than 100 students took to the streets a week later to clean up the neighborhood, hoping to repair their school’s image.

When Araceli Quezada’s daughters were starting high school at Aurora Central, they were skipping classes, and having trouble engaging with school, but she credits the school’s attention to turning them around.

Quezada said school officials sat down with her and her daughters to set goals and talk to them about the consequences of missing school. Her daughters graduated in 2018 and 2019.

“I’ve seen the way the school talked to them,” Quezada said. “I’m pretty sure if the school had not approached them the way they did, they would not have graduated.”

It’s also a contrast to the experience of an older daughter who Quezada said was able to graduate from Aurora Central in 2009 because she was a self-starter, even though she noticed the school wasn’t engaging most students at that time.

The school’s state rating decreased slightly this year, as did some state test scores. The school’s average scores on the SAT are lower than Adams City High School’s, another chronically low-performing school under state orders to improve.

Papa Dia, a district parent and community activist, said that he believes the school and the district still have a way to go in helping non-English speaking families — a large portion of the Aurora Central community — engage with schools.

For instance, he said, more home visits are needed. Teachers started doing home visits in 2018, in some cases in place of parent-teacher conferences, but Dia said most of the immigrant and refugee families he works with have not had a home visit.

“I think home visits would be very important in engaging with the families and getting families involved,” Dia said. “Families don’t understand the report card or how the kids are graded or what is a good grade, so most of the time they cannot help the kids with their homework.”

Engaging with families, Dia said, would allow the school to connect families to resources so that parents can find additional help for their children outside of school.

As of last week, district officials said the school had conducted almost 300 home visits this year. In the last two years, school officials have done about 1,600 home visits, a district spokesman said.

The school has also tried to increase parent engagement with dedicated staff, regular “parent coffee” meetings where officials talk to parents about different topics, and with a more involved Parents in Action committee.

Quezada said she attended the parent coffee meetings, but would have liked to have been more involved.

“Sometimes you can’t do it because of work,” she said. “I’ll be more involved with my grandkids.”