There’s ample evidence that the school where I work, Northeast Early College on the outskirts of Denver, prepares students for college.

The majority of our students are enrolled in college classes, offered on campus tuition-free by the professors who make up over 50 percent of our staff. Our pass rate for these classes exceeds 80 percent, and our graduating students’ persistence rate in college rivals the best in the district. More than 85 percent of our graduating student body leaves our campus without needing remediation in college math or English, and many of our graduates leave us with a year’s worth of college credits. Our most ambitious students can receive associate’s degrees concurrently with their high school degrees.

And yet Northeast Early College is rated “Accredited On Watch,” or not meeting expectations, on Denver Public Schools’ rating system, the School Performance Framework.

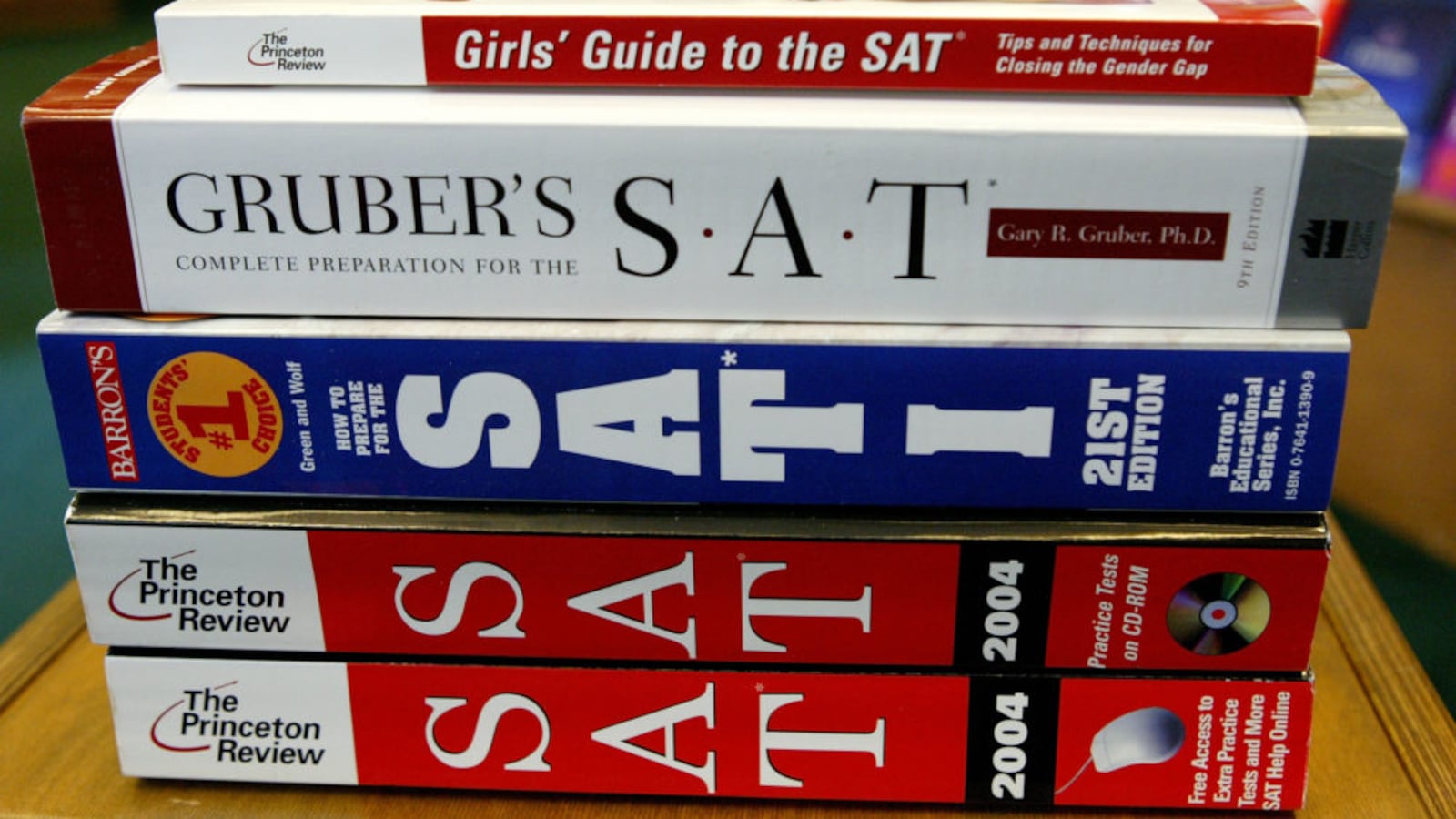

That’s because the rating system, which the district developed to hold schools accountable to their results and in hopes that this accountability would begin to narrow the city’s yawning achievement gaps, bases the majority of high schools’ ratings on their students’ PSAT and SAT scores. State law requires all Colorado 9th-, 10th-, and 11th-graders to take these tests.

The exact weight of SAT scores on Denver’s school ratings changes frequently as the district revises its rating system, known as the SPF. But last year, SAT scores made up more than 60% of schools’ ratings — penalizing schools serving the low-income students whose performance the district is most concerned with improving, and rewarding schools serving affluent student bodies at the expense of others.

The district’s choice to focus on SAT scores is surprising, given the abundance of research that demonstrates a deep and persistent correlation between the scores and socioeconomic status. Basing the significant majority of a school’s rating on student SAT scores virtually guarantees that schools that serve low-income students will perform poorly, while affluent schools will shine.

This is exactly what has happened in Denver. Not one of the public non-charter high schools in the city that serves a majority low-income student body is meeting expectations on the School Performance Framework. Denver School of the Arts, the district’s sole non-charter school with a top “blue” rating, serves a 90% economically advantaged population and requires an audition for admission.

Research has also shown that success on the SAT is not a predictor of college persistence or performance, so its role as the dominant measure for school success is out of step with the district’s expressed priority of post-secondary readiness. Aware of the SAT’s racial and socioeconomic inequities, dozens of highly-ranked colleges have stopped requiring the SAT for admittance, and even the College Board recently rolled out plans (since abandoned) for assigning an “adversity score” meant to even the playing field for students from low-income homes and for whom English is a second language. Yet Denver remains far behind the rising chorus of voices advocating for equity where the SAT is concerned.

Denver has long expressed priorities around closing achievement gaps and supporting students’ emotional needs as well as their academic ones. To my mind, a true commitment here would include helping students graduate without needing remedial classes in college, investing in career and technical education, and getting low-income students the academic and social-emotional support many of them so desperately need — none of which is emphasized in the rating system.

Instead, only about 30% of schools’ ratings comes from graduation rates and student enrollment and pass rates in concurrent enrollment and Advanced Placement courses — even though success in concurrent enrollment classes is considered a reliable predictor of college persistence, unlike the SAT.

Things are clearly broken with Denver’s school rating system. Though the district has recently convened a task force of teachers, parents, and administrators to make recommendations for reimagining the SPF, it is unclear to what extent Denver Public Schools is truly willing to reassess what success looks like for high school students.

Northeast Early College is doing the work of educating students for a 21st-century post-secondary experience: lessening their potential student debt, increasing their college persistence, and amplifying the confidence and self-advocacy of first-generation college students. It’s a shame that our district’s severely limited School Performance Framework neglects to measure us — and other schools that are taking a similar approach, with similar results — by the richness of that work.

The author is a ninth-year English and concurrent enrollment educator in Denver Public Schools. She is a teacher leader and coach at Northeast Early College, a former Teach Plus Fellow, and a current member of the Teach Plus cabinet.

About our First Person series:

First Person is where Chalkbeat features personal essays by educators, students, parents, and others trying to improve public education. Read our submission guidelines here.