Back in December, my editor and I talked about doing a story on which reading curriculum Colorado school districts use in kindergarten through third grade — a new angle on the reading instruction debate we’d followed for more than a year.

I imagined a service-minded final product. We’d ask school districts to report their reading curriculum — the roadmap for what and how teachers teach. Then, we’d link up those names with ratings, and make it all available to readers. With a few clicks, parents and the public would have an easy way to find out key details about how Colorado kids are learning to read.

As usual, things are messier in real life.

All told, four other reporters and I worked on the information-gathering part of the project, sending public records requests to Colorado’s 30 largest districts plus three charter networks. As the information started coming back throughout January and part of February, we were awash in curriculum names — Journeys, Wonders, Benchmark, Reading Street, Storytown, Superkids, Lucy Calkins.

There were more than three dozen in all, including some written by teachers or school districts. Some curriculums were rated by the state or an outside evaluator, but many weren’t. State ratings often matched those from the outside evaluator, but not always.

A few districts did not cite any comprehensive program, known as core curriculum, meant to reach all students. For example, the Denver district reported that one school uses “Montessori,” which is an approach to education, not a reading curriculum. It reported another school uses “Genre Study,” which is exactly what it sounds like: A program to teach students about literary genres. A couple of districts reported using a jumble of supplemental programs, all addressing different concepts.

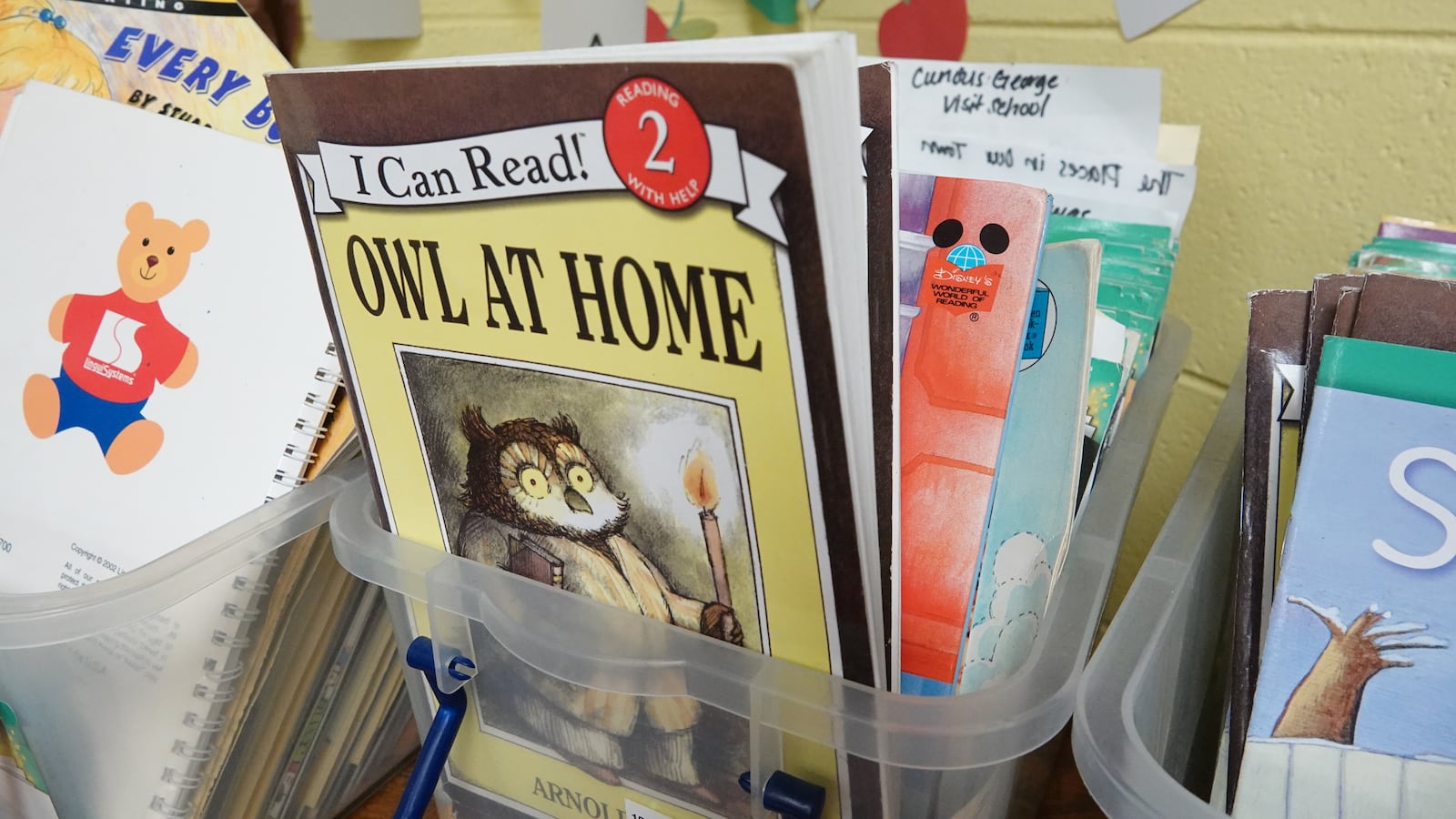

We visited four elementary schools to get a snapshot of reading instruction in action. Without exception, we saw smart, caring teachers who wanted their students to learn to read well. But as our bulging curriculum spreadsheet indicated, methods and priorities varied from school to school and district to district.

Just as we were preparing to publish this project a few weeks ago, the coronavirus pandemic swept in — taking over the news cycle and all our reporting power. We put the curriculum project on hold. While there’s still plenty of concerning coronavirus news, we believe there’s room now to tell this story, too.

I hope our findings and our reporting shed light on the world of reading curriculum and arm parents and the public with the information they need to ask deeper questions about reading instruction.

Earlier, we reported on how teacher prep programs cover reading instruction, why many teachers feel poorly prepared to teach reading, the legislative push for reading instruction remedies, and a new crop of public schools designed for dyslexic students.

For me, this latest project is one more piece of our ongoing coverage. It answered that original question from December — though not as neatly as I’d imagined, and raised more questions that I hope to dig into over the next year. If you’d like to chime in with your thoughts, drop me a line at aschimke@chalkbeat.org.