Tuesday was supposed to be Denver’s 138th day of school this year. But in a lot of ways, educators said it felt like the first day all over again.

That’s because Denver Public Schools transitioned to remote learning after a three-week “extended spring break.” Denver schools, which serve more than 92,000 students, will remain closed to in-person learning for the rest of the school year to stop the spread of coronavirus.

Last week, Chalkbeat chronicled how Denver educators were preparing for the monumental shift. We checked back in with some of them Tuesday, as well as with other teachers, principals, parents, and students to ask what went well — and what could have gone better.

Here’s what they said.

🔗Melea Mayen, teacher, Northfield High School

Mayen held her first virtual office hours at 9 a.m. Tuesday — an early hour many of the teenagers in her classes likely hadn’t seen in weeks. Still, seven of the 10 students in her first class showed up, including a boy whose entire family has COVID-19.

The students were eager to check in on each other — and especially on their ill classmate, whose family is recovering. Even her quietest students joined in.

“They were being so real about it,” Mayen said. “They were like, ‘I don’t really know you that well, but I miss you.’ … You can tell they really miss the community of school.”

Rather than focus on academics, Mayen briefly explained the assignment and reserved the rest of the time for chatting. Families with multiple siblings sat at their kitchen table and passed a laptop so each of them could say hello. Students introduced their dogs. A girl in Mayen’s speech and debate class showed off her pet sugar gliders. One animal got stuck in her couch.

“So we’re talking about speech and debate, and she’s pulling the cushions off her couch, trying to find her sugar glider,” Mayen said. It wasn’t what the teacher expected. But it was good.

“It was so nice for the students to be able to share,” Mayen said.

🔗Danielle Short, parent, McKinley-Thatcher Elementary School

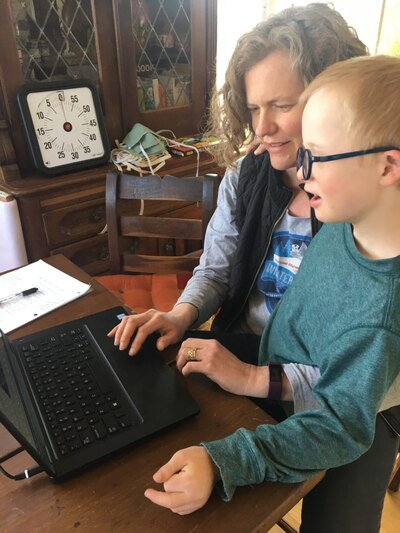

For Short and her second-grade son, Tuesday didn’t really feel like a school day. Instead, it felt like another planning day as Short and her son’s special education team continued to work out what remote learning will look like for Micah, who has Down syndrome.

Micah logged on at 8 a.m. for a class meeting with his teacher and classmates. The students each took turns answering a question tied to a unit on pollinators they’d been studying before the break: Would you rather be a bee or an ant? Micah’s answer: ant.

Micah then did some schoolwork, and Short virtually huddled with members of Micah’s team. At school, he gets support from a special education teacher, a one-on-one aide, an occupational therapist, a speech therapist, and the school psychologist. In addition to his second-grade class, Micah’s school is also holding remote gym, music, and art classes. And Micah participates in therapy outside of school, too, which is now being done online as well.

The task of organizing it all is daunting.

“Everybody is doing their darnedest,” Short said. “It’s just a challenging situation.”

🔗Amy Bergner, teacher, Columbian Elementary School

With two classes of students and three children of her own, Bergner juggled the dual roles of parent and teacher Tuesday. That meant navigating five virtual classrooms and more than 80 texts, emails, and Facebook messages with questions that ranged from the simple — “How do I log in?” — to the complex: “What are the academic expectations here?”

“It’s been crazy,” Bergner said.

A highlight was watching her fourth- and fifth-grade students reconnect. They swapped stories about video games and playing outside. One boy showed off his week-old baby brother. Asked how they were feeling on a scale of 1 to 10, all of Bergner’s students said they were an 8 or a 9.

But there were hiccups too, like when Bergner’s third-grade son got disconnected from his virtual class meeting at the same time Bergner was holding a class meeting of her own. She had to excuse herself, run upstairs, log her son back on, and then dash back to her class.

By the time the traditional school day ended at 3 p.m., Bergner, who woke up at 5:30 a.m. Tuesday, had at least one more important task on her to-do list: Log in to yet another virtual classroom to help her youngest child, a kindergartner, with her schoolwork.

🔗Rachel Kurtz-Phelan, parent, Westerly Creek Elementary School

When Kurtz-Phelan tried to log into her kindergarten daughter’s Google Classroom Tuesday, she got the most dreaded of messages: “This classroom does not exist.”

It took her and her husband an hour to work out the technical difficulty. But once her daughter Macy was logged on, Kurtz-Phelan said the first day of remote learning went smoothly.

“All things considered, it went as well as it could,” she said.

Macy’s class had started the day on a video call, where they sang their usual welcome song and did their daily phonics flashcards. After the call, and after her parents figured out the Google Classroom log-in, Macy zipped through her math assignment in five minutes. Using a blue marker, she then finished this sentence: “Over spring break…”

“I made aret projics and lrnd haw to ride with out chrarening wols,” Macy wrote.

(Translation: I made art projects and learned how to ride without training wheels.)

All of it took about an hour, Kurtz-Phelan said. Did Macy like doing school with her mom?

“A little bit,” she said.

🔗Alondra Gil Gonzalez, student, CEC Early College

The best part of the start of remote learning for Alondra was watching her brother’s first day of classes.

“They were having an all eighth grade Zoom meeting and it was pretty funny to watch,” she said.

Alondra is a senior at CEC Early College, a school that sent her full-time to Community College of Denver to earn her associate degree before her campus closed.

Alondra actually began remote college classes last week, she said, and the format has presented upsides and downsides for the 17-year-old student.

The virtual learning is allowing her more time to help with her family’s coffee and ice cream shop. But Alondra said she’s a hands-on learner, and most of the communication with her professors is through email.

Alondra said she’s needed to create lists to keep track of assignments so she doesn’t get behind.

And the absence of friends is also incredibly difficult.

“As seniors, it feels like our last moments are kind of being ripped away,” she said.

🔗Shane Knight, principal, Knapp Elementary School

On the first day of school, Knight typically pops into classrooms, getting a sense for how students are feeling and what they did over the summer. Tuesday, he said, felt no different.

He saw joy on students’ faces as they greeted each other for the first time in several weeks and talked about spending more time with family since schools have been closed.

He also heard concern: Many students at Knapp have a parent who has lost a job, Knight said. Others are concerned that parents who are working at retail stores might come home sick. One mother has been in the intensive care unit since Thursday.

Knapp, where nearly all students come from low-income families, has also struggled to get computers and tablets to every student. The school is still 190 devices short, and Knight is hoping a combination of private donations and district computers will fill the gap.

But for the students who were able to connect Tuesday, Knight said the drive to learn was strong. In one fifth-grade class, a student asked if they still had to take state standardized tests this spring. No, the teacher said. But it’s no less important that you try your hardest.

“She said, ‘The learning we’re doing today is not just for this day, it’s for the rest of your lives,’” Knight said.

Several students on the video call raised their pinky and their thumb and shook them back and forth, a silent gesture of agreement that gave Knight great hope.

🔗Juan Pedro Garduno, teacher, STRIVE Prep – SMART

The return of school on Tuesday marked the beginning of clarity for Garduno.

The veteran math teacher said the last few weeks of “extended spring break” meant scrambling to get students resources for the year-end Advanced Placement exams. But he was left wondering what instruction would like.

Now, his students are pushing forward with preparations for the AP exam, which will be offered online in an abbreviated format.

“Even though it’s not ideal,” he said, “at least we know what we’re supposed to be doing. We have very clear targets.”

Garduno’s students were greeted during the first day back with a 20-minute video math lesson that they could watch at any time during the day. He also said he plans twice-weekly homework assignments and will hold office hours to answer questions.

“Many of our students have challenging life situations where they are working to either not feel like a burden on their parents or, in some cases, actually helping out their parents,” Garduno said.

Garduno said there were few downsides to being back in school, even if it’s remote. For most of his students, he said, school is welcomed.

“Now that we have structure, I think it’s going to be better,” he said.

🔗Cameron Thorstad, teacher, Grant Ranch ECE-8 School

Remote learning for special education teacher Thorstad mirrored what he already does in the classroom.

During a Google Classroom meeting, he joined another teacher to help his special education students learn the lessons of the day, just as he joined colleagues in their physical classrooms before the closure.

The new learning format gives Thorstad the opportunity to help more students than usual.

“At this time, I kind of support not only my students that are specifically assigned to me but kind of all the ones that are in the classroom,” he said.

Although the structure remains similar and teachers are working hard to build a familiar routine for students, the shift is not without challenges.

Thorstad needed to hold one-on-one video chats with parents who don’t understand the technology. Some of his students with disabilities struggle with the online format or don’t have the attention span to watch a screen for very long.

Thorstad said he is reassuring parents that it’s OK if students can’t sit through an entire lesson.

“We’re going to sustain as much as we can and then we’re going to take breaks when we can,” Thorstad said. “And we’re going to get as much work done as we can. And then we’re going to adjust and modify as needed.”

Because if his students can learn at least a few lessons during this time, he said, that’s a win.

This article answers questions raised by our readers. Share your coronavirus-related questions, concerns, and ideas by emailing us at community@chalkbeat.org, and keep up with our reporting on COVID-19 here.