Stefanie Kovaleski loves teaching kindergarten at Detroit’s Bethune Elementary-Middle School.

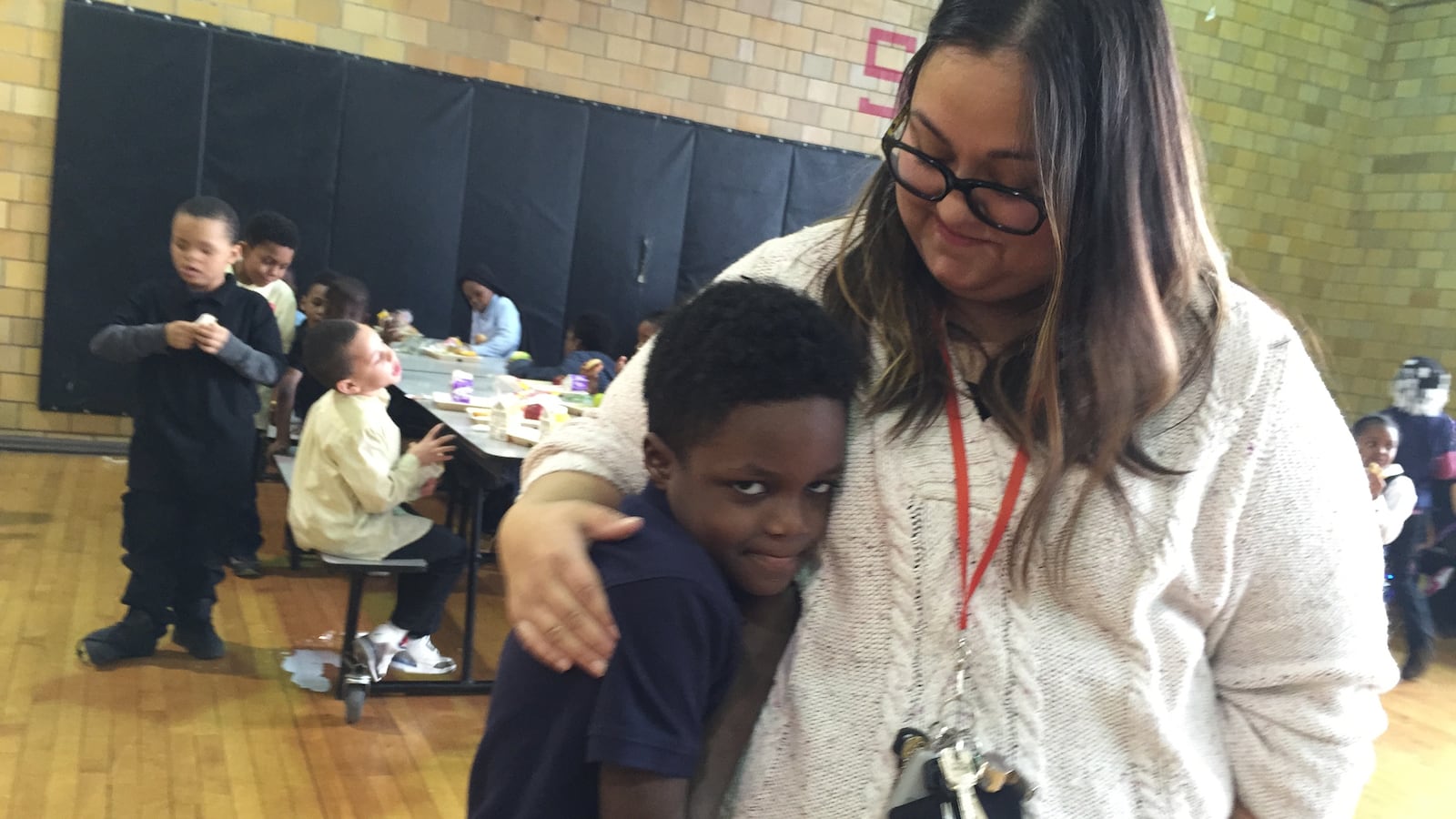

“I love this building. I love the kids in it,” she said as she doled out hugs and high-fives to her young students while they lined up to get their backpacks at dismissal. “I love that I have autonomy and that I’m treated with professionalism here.”

She hopes to stay in her classroom and remain a part of her students’ lives, she said, but she’s actively talking to banks and credit unions about working outside education.

“I can’t see myself out of teaching but I’ve definitely started looking in the private sector,” she said.

Kovaleski, 33, is one of many teachers in the state-run Education Achievement Authority who say they’re considering leaving their schools in what some fear could be a mass exodus — the kind of disruption that could drive down test scores, drive up behavioral issues and create new challenges for children whose lives are already tumultuous.

“These children have very little stability in their lives,” Kovaleski said of a school where 98.7 percent of students are identified as “economically disadvantaged” by the state. “The people in this building are the only stable people they have.”

The EAA teachers fear major pay cuts and changes to school leadership when their schools return this summer to the main Detroit school district after five years of state control. Their departures could undermine a group of 11 schools that have weathered multiple changes and enrollment declines since they were taken out of the Detroit Public Schools in 2012 and put into the state’s recovery district.

As the two districts prepare to reunite July 1, officials in both districts say they’re taking steps to ensure as much stability as they can.

The main district — now called the Detroit Public Schools Community District — extended offers to all EAA teachers who have not been rated ineffective so they can stay in their current jobs.

The Detroit school board this week lifted a hiring freeze that had been holding up decisions about principal and assistant principal jobs in the schools.

And leaders from both districts have been meeting regularly to discuss details of the transition, from summer school to building upgrades.

But with just weeks to go before the end of the school year, EAA teachers still don’t know what their salaries will be next year or who their principals will be and they’ve grown impatient with the lack of information.

“Many of us now feel that our backs are against the wall,” wrote Rubye Richard, an English teacher at the EAA’s Mumford Academy High School, in one of many letters EAA teachers have written to the Detroit school board in recent weeks.

“If decisions are not made and communicated to us, we are forced to continue searching for employment in other districts,” she wrote.

The delay in teachers knowing their salaries is related to the fact that the main district is negotiating a contract with its teachers union.

If negotiations don’t change salaries much from the current contract, EAA teachers could see major pay cuts. First-year EAA teachers, who are not in a union, now make $45,000 a year compared to less than $36,000 for their unionized DPSCD counterparts.

Some of the pay discrepancy is because EAA teachers worked summers while Detroit district teachers can make extra money teaching summer school. A DPSCD spokeswoman noted that the main Detroit district also pays more generous benefits than the EAA.

But the larger impact on EAA teachers will come from the decision about how much experience EAA teachers will be given credit for when they become DPSCD teachers.

When the EAA calculated teacher salaries, it gave new hires credit for all their years of experience. That means Kovaleski now makes $65,000 a year — a salary based on ten years of teaching including four years at Bethune, one year in the Dearborn school district and five years at a Detroit charter school.

But under Detroit’s current union contract, new teachers to the district typically get just two years of credit, regardless of how long they’ve worked in other districts.

Though the contract lets the district credit teachers with up to eight years of experience under special circumstances, such as critical vacancies, teachers like Kovaleski could essentially have to start from scratch.

The current Detroit teacher contract pays $40,643 to teachers with a master’s degree and two years of experience so Kovaleski could be looking at a nearly $15,000 pay cut.

Kovaleski’s mother lives with her, has congenital heart failure and $50,000 in debt from a recent hospital stay, she said. “The bills keep rolling in so when I stop and think, man, can I afford to take [a pay cut]? I just don’t know.”

Teachers union president Ivy Bailey said she regrets that some EAA teachers might take pay cuts. But she also notes that teachers in the main district have had stagnant wages for years.

“It would not be fair for someone from the EAA with only two years to come in here and make more than a teacher who has been here and … weathered the storm through all of this,” Bailey said.

The uncertainty has already driven some EAA teachers out the door.

District data show that 43 percent of EAA teachers did not come back for the current school year — twice the attrition rate from the year before. And principals say more teachers than usual have left mid-year.

At Bethune, principal Alisanda Woods said four of her 32 teachers have left since September.

Some left because they were worried about their salaries in DPSCD, Woods said. Others left because Bethune was one of 25 Detroit schools that were threatened with state closure this year. The closures were averted when the district this month signed a “partnership agreement” with the state, but some teachers were already gone.

Massive teacher turnover isn’t necessarily a bad thing if it’s part of a deliberate improvement plan, said Dan Goldhaber, the director of the University of Washington’s Center for Education Data & Research.

In Washington D.C., public schools saw improvement as a result of teacher turnover. “It was a very high functioning school district investing a lot of effort into screening new teacher applications and encouraging ineffective teachers to leave,” Goldhaber said.

But absent an effort like that, he said, studies show that too many new teachers will hurt kids. “Even if you were to replace a teacher with a second teacher of equal quality, just the disruptive effect of a teacher leaving will have” a negative impact, he said.

EAA Chancellor Veronica Conforme, who is leaving Detroit to start a new job in July, said she’s been working closely with her DPSCD counterparts to keep the EAA schools as stable as possible after the transition, but unanswered questions about teachers and principals are making that difficult.

“I’m really worried about the fact the we haven’t finalized offers” for teachers, Conforme said. “It’s the middle of May … That’s deeply concerning.”

The EAA schools, which were put into the district originally because of years of poor results, are still some of the state’s lowest-performing schools, but most of them have seen recent improvements. Conforme said she worries that progress could be disrupted if teachers leave.

The main Detroit district is already trying to fill more than 200 vacant teaching positions.

The EAA schools saw dramatic teacher turnover back in 2012 when the new district began.

“There was a big shakeup,” said David Arsen, a Michigan State University professor who wrote a paper on the early years of the EAA. But that big shakeup wasn’t well planned, he said. “The EAA was a spectacular train wreck right out of the gate.”

These years later, he said, he was hoping the process of returning the EAA schools to the main district would be smoother. (Of the original 15 EAA schools, three have been converted to charter schools and one has closed).

Conforme said she hopes most of her teachers ultimately will decide to stay because if they leave, families will follow.

“What families and students care about is that there’s consistency with the teachers that have been teaching them, the support staff that have been supporting them and the leaders the families have gotten comfortable with,” Conforme said. “That part is critical.”