LaWanda Marshall and Candace Graham both teach pre-kindergarten at the Carver STEM Academy on Detroit’s west side.

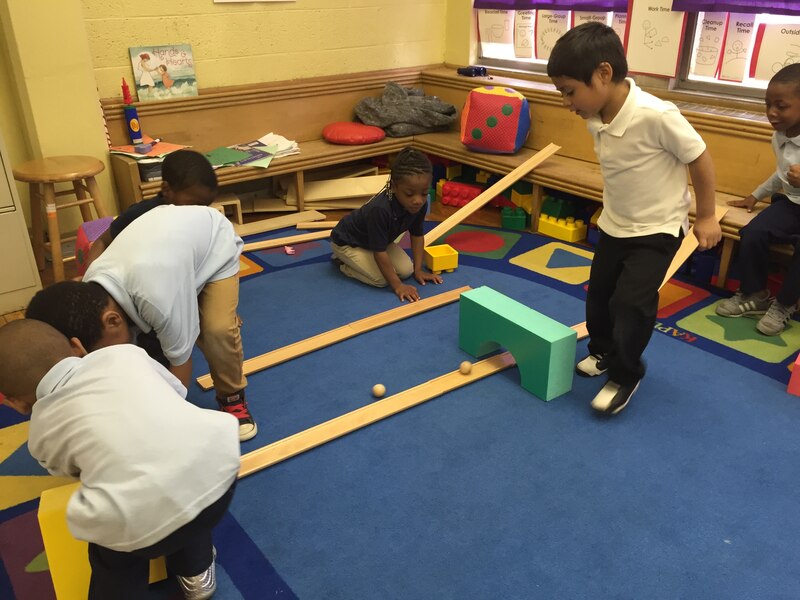

Both have colorful, toy-filled classrooms, computers for students to use and assistant teachers to help guide their four- and five-year olds as they learn and explore.

But Marshall’s classroom has other things too — lots and lots of other things that regularly arrive like gifts from the pre-K gods.

“The office calls and says you have a package, and we’re like ‘Yay!’ and the kids get excited. It’s like Christmas,” said Marshall. Boxes filled with classroom supplies like musical instruments and science kits arrive every few weeks.

Marshall’s students — part of the Grow Up Great program funded by the PNC Foundation — go on regular field trips and get frequent visits from travelling instructors. The parents of her students get access to support programs like one that connects job seekers with employment opportunities. And Marshall receives special training in teaching arts and sciences that she credits with upping her game as an educator.

Graham and her students, meanwhile, hang back when the kids down the hall board the bus to go on field trips. Few packages or visitors arrive.

“We get left out a lot,” Graham said. “It’s unfortunate because I feel like all the kids should have the opportunities … They get more resources than we do. They have more materials in their classroom.”

The tale of two pre-Ks at the Carver STEM Academy is a problem well known in high-poverty school districts like Detroit that rely on the generosity of corporate and philanthropic donations to pick up where government resources leave off.

Districts are happy to accept gifts from private donors — baseball tickets or classroom supplies or money for school renovations. But inevitably, there’s not enough to go around. Schools then have to choose.

At Carver, all of the pre-K students are getting a quality education and a leg-up on school. But the children in Marshall’s classroom get to experience a program that shows how much more is possible when teachers have enough resources to fully involve parents, to engage community partners and to focus as much on science and art as they do on the ABCs.

The pre-K enrichment program is in 38 Detroit classrooms including 28 that receive PNC Grow Up Great funding and 10 that are supported by the W.K. Kellogg Foundation.

Children in most of the city’s 177 pre-K classrooms don’t get to participate. That’s an inequity that Pamela Moore says she’d like to change.

Moore heads the Detroit Public Schools Foundation, which raises private funds for district schools. She’s trying to raise money to expand the program to all of the district’s preschools.

“We’ve got lots of partnerships so some kids get some things. Other kids get other things … but a lot of money is needed,” she said.

Moore is also looking for new ways to distribute private dollars so things like donated equipment or invitations to the Grand Prix are more coordinated — and less like a game show with prize-winning contestants.

“You’re the winner!” Moore said. “You and you and you. If we could coordinate that, maybe everyone could get a field trip or two and teachers could plan on it and count on it.”

* * *

The PNC Foundation launched Grow Up Great in 2004, investing $350 million in quality education for young children across the nation. The bank’s effort was part of a national push from philanthropists, advocates and governments to help children become better prepared for school.

“For every dollar spent on high quality early education, the society gains as much as $13 in long-term savings,” said Gina Coleman, a PNC vice president and community relations director.

PNC approached the Detroit school district about participating in 2009, said Wilma Taylor-Costen who at the time was an assistant superintendent in charge of district early childhood programs.

District officials worked with PNC to design a program that would expose kids to the arts and sciences through extra classroom resources and partnerships with museums and arts organizations, Taylor-Costen said. The idea was to connect families with those groups through field trips and classroom visits, and to train teachers so the benefits would continue even if the money dried up.

“It has been an awesome opportunity for exposure of not just our children but their families,” Taylor-Costen said.

When kids in the program go on field trips, their parents come along. This year that included trips to the North American International Auto Show, the Grand Prix education day at the Palace of Auburn Hills, the Cranbrook Science Center and a Music Hall puppet production of Eric Carle’s Very Hungry Caterpillar.

Parents also benefit from classes and programs that help them support student learning at home.

And Marshall credits the program with expanding her approach to teaching preschool after 22 years in the classroom.

“The professional development has been key, very valuable,” Marshall said. “Before, I focused on the reading and the math and making sure they could write their name. Now I know that by incorporating arts and sciences … I’m adding that missing element.”

Tayor-Costen said she couldn’t recall how classrooms were selected for the program but said district officials made sure to include schools in different city neighborhoods.

* * *

Principal Sabrina Evans first brought the PNC program to Carver when she came to the school in 2012. She had seen the program at her prior school, the Beard Early Learning Neighborhood Center, and wanted it for Carver’s pre-Ks, she said.

“For them to have the first time going to school with all these things at their disposal, it’s like ‘Wow! I like school!’ Not only the kids, but the parents. I see more parents coming to the field trips and then I see them coming to school to participate.”

Evans was able to put both of Carver’s two pre-K classrooms into the Grow Up Great program in 2012 but when the school added a third pre-K in 2016, there wasn’t room for a third Carver classroom in the coveted program.

That’s why Graham’s students can’t participate.

“It’s lonely,” Graham said. “A lot of times we don’t even know when they have somebody coming to their classroom because it’s almost like a secret society.”

On a recent morning, when Graham’s class came out to play on the playground, her students ran past students in the school’s two PNC classrooms. The PNC kids were launching bottle rockets they had learned to make when visitors from the Charles H. Wright Museum, a new partner, brought bottles, baking soda and vinegar to the school.

Evans said she tries to support Graham’s classroom with other resources. She sets aside $20,000 from her budget every year to pay for school-wide field trips (Marshall’s students go on those field trips, too). And Marshall says she shares as many classroom resources with Graham as she can. She also passes along ideas and tools she develops through the supplemental teacher trainings.

But Evans regrets that some of her classrooms get benefits that others do not.

“I’m blessed to have two [PNC classrooms] because some schools don’t have any,” she said “But … If they’re going to offer it, it should go to every pre-K class in the district.”

Moore has been trying to raise money to expand the program — and continue it in case the current funding dries up.

Last year, Moore put together a proposal to share with potential funders that put the cost of the program at $882 per child per year.

“PNC was the one that stepped up and said they were going to write a check and … we were so excited about that investment, we just said ‘woo hoo!’ and took it,” Moore said. “But now it’s time, if we all agree that it’s valuable … to go and find the resources.”

Moore is encouraged by the Hope Starts Here initiative, led by the Kellogg and Kresge Foundations, which has brought parents, experts, community organizations and political leaders together over the past year to develop a city-wide strategy to improve the lives of young children in Detroit.

“Hope Starts Here is an excellent example of bringing everybody into the room, figuring out where the gaps are and coming up with a plan we all agree with,” Moore said. “Then we’ll have a road map.”

Kellogg has been funding programs in the Detroit Public Schools for years but has recently ramped up its focus on early childhood education, said Khalilah Burt Gaston, a Detroit-based program officer with the Battle Creek-based foundation.

The foundation has worked closely with district leaders, she said, but the string of state-appointed emergency managers in recent years has made city-wide collaboration with the district challenging. “I think it would be fair to say that it’s been difficult during transitioning leadership to articulate a clear vision and strategy,” Gaston said.

That could change now that the district has a new superintendent, Nikolai Vitti, who has said he plans to stay for at least five years. Gaston said Hope Starts Here hopes to work with the district as it looks for new ways to expand high-quality early childhood programs.

Grow Up Great offers one model that the planners are looking to, she said. “It’s wonderful but it’s only serving a small number of children so what are the strategies needed to scale that? Replicate it across the entire district?”

Coleman said PNC knew that limited resources would prevent the bank from providing the program to all of the district’s preschoolers. The goal, she said, was to show what can be accomplished with extra funds.

“Obviously you can’t help every classroom,” she said. “But we have helped set the bar in how it can look.”