The school building that Detroit Prep founder Kyle Smitley is trying — and struggling — to buy for her charter school is far from the only one sitting empty across the city.

A wave of about 200 school closures since 2000 has pockmarked the city with large, empty, often architecturally significant buildings. Some closed schools were repurposed, most often as charter schools; others were torn down. But most remain vacant, although the exact number is unclear.

Vacant schools can become crime hubs or crumbling dangers. But even if that doesn’t happen, they are disheartening reminders of Detroit’s struggle to prioritize education for its children — at the heart of communities where good schools could make a big difference.

Most residents would like to see the buildings come back to life, if not as schools, as something. But even as developers rework other vacant structures, these school buildings are rarely repurposed.

Understanding why illuminates the complexities facing Detroit’s main school district’s effort to get itself back on track.

For one, school district policies — some of which were created to discourage flipping and the opening of charter schools — have made selling these buildings difficult.

Smitley, the co-founder of two charter schools, wants to move Detroit Prep into the former Anna M. Joyce Elementary School by fall 2018. Detroit Prep opened in 2016 in the basement of an Indian Village church and will eventually serve 430 K-8 students.

“We’d like to be part of a positive story for Detroit, and turn a decrepit building back into a school that serves the neighborhood,” Smitley said.

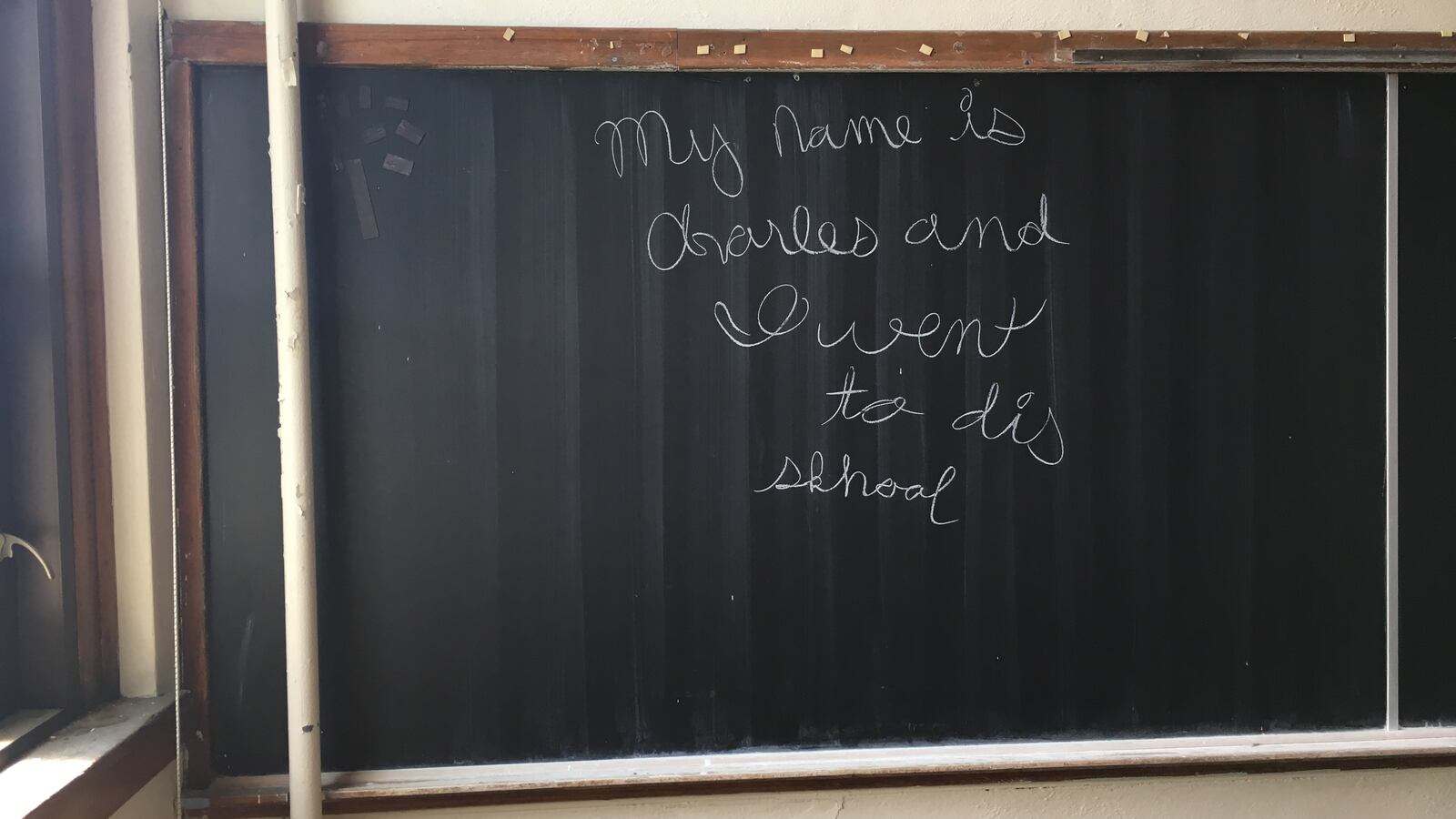

Smitley is preparing to do a $4 million rehab on a building where flaking paint litters the hardwood floors. Lockers gape open. Natural sunlight floods classrooms where instructions from the last day of school are still chalked on the blackboard: “Spelling Test … George Washington Carver Reading – Timed … Clean Desks … Take Books.”

Landlord Dennis Kefallinos bought the former Joyce school from the public school district in 2014 for $600,000. The general manager of Kefallinos’ company told Chalkbeat that they planned to repurpose it for residential use when the market seemed right, or wait a few more years to re-sell it for a large profit.

But another challenge of repurposing schools is that their complex layouts and their residential locations far from downtown do not easily adapt to other uses. And the market for former school buildings was flooded with closed public and parochial schools in recent years, which further reduced demand.

Some developers have transformed empty Detroit schools into apartments, luxury condominiums, or a boutique office building. However, these were former Catholic schools, or, in the case of Leland Lofts, sold to a private developer more than 35 years ago. Catholic schools generally have smaller footprints, which are more manageable to renovate, and they do not have the same deed restrictions as more recently closed public schools.

In the case of Joyce school, Smitley’s persistence and the intervention of a mutual friend convinced the Kefallinos company to sell to Detroit Prep. She agreed to buy the building for $750,000, and to pay the district $75,000 on top of the sales price, per a condition in the original deed.

But the status of the sale is uncertain, as she and the district spar over the law and whether the district can halt the sale of the building — which it no longer owns.

On the northwest side of Detroit, two Detroiters have been trying for years to buy the former Cooley High School to turn it into a community center, as part of the much-lauded Cooley ReUse Project. This summer, it was crowdfunding the last $10,000 it needed to finally become Cooley’s owners.

But on August 31, the project’s social media account announced that “after meeting with Detroit Public Schools Community District’s (DPSCD) new leadership, it has been confirmed that Thomas M. Cooley High School is no longer for sale. We were told that Cooley will be secured and redeveloped by its current owner, DPSCD.”

Donations are being returned to the contributors. In the meantime, the 322,000-square-foot building is vulnerable to theft and vandalism, destabilizing its northwest Detroit neighborhood.

The Cooley and Joyce schools were built when Detroit schools faced a different challenge: capacity. They opened during the fast-moving period between 1910 and 1930 when 180 new schools were built to keep up with growth. In 1966, the district peaked with 299,962 students. Since then, it has shrunk to fewer than 50,000 students.

No matter who owns a closed school building, its revival depends on its security. Failure to secure it results in profound damage by scrappers, criminals, and natural elements. That will either add millions to the cost of rehabilitation or doom it to demolition. It also threatens the neighborhood.

John Grover co-authored a major Loveland report, spending 18 months investigating 200 years of archives about public schools in Detroit, and visiting every school in the city.

Boarding vacant schools with plywood isn’t enough, he learned. As its buildings were continually vandalized, the district escalated security with welded steel doors and cameras, though even these are vulnerable. Securing a building properly costs about $100,000 upfront, and $50,000 per year ever after, according to the Loveland report. In 2007, it cost the district more than $1.5 million a year to maintain empty buildings.

Chris Mihailovich, general manager of Dennis Kefallinos’ company, said that it hasn’t been cheap to own the empty Joyce building. Taxes are high, security is expensive, grass has to be mowed in summer and snow has to be shoveled in winter.

The Joyce school is in better condition than most, which Grover credits to its dense neighborhood. “At least up until a few years ago, a retired cop lived across the street, and he watched the block and would call in if he saw anything,” Grover said.

But he remembered the fate of one elementary school in east Detroit that was in a stable neighborhood when it closed.

“It became like a hotbed for prostitution and drug dealing,” he said. “There were mattresses stacked in the gymnasium. It definitely had a negative impact on the neighborhood. … I can’t imagine people would want to live around that, and those who could get out did.”