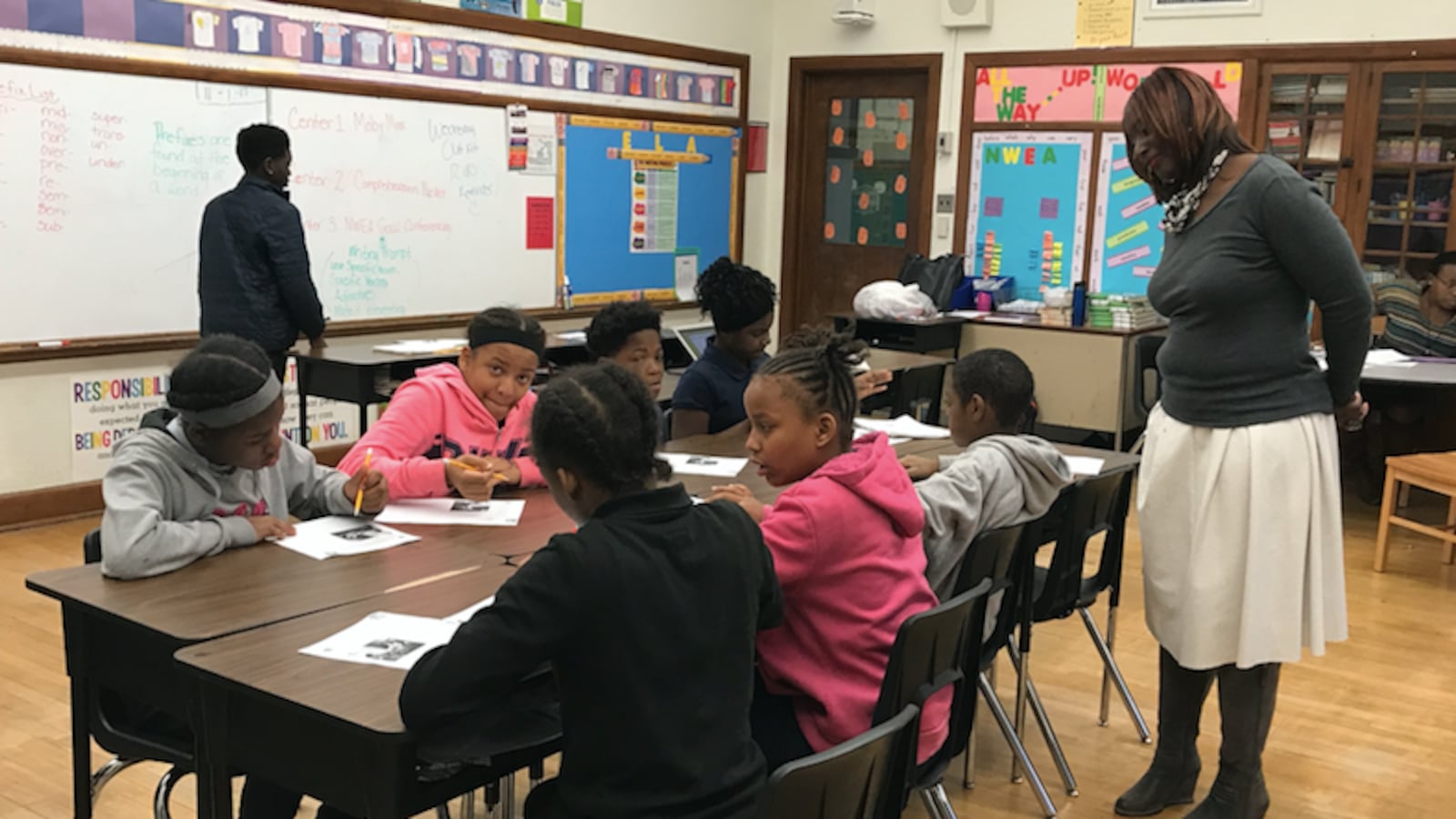

Students were clearly hard at work when Principal Alisanda Woods stopped by her school’s sixth grade English class one morning last month.

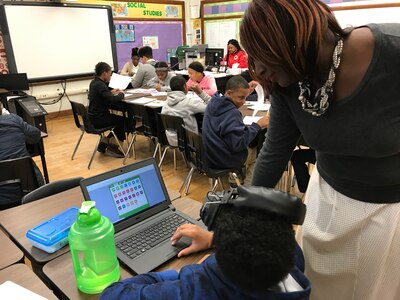

Some of the sixth-graders were working on a writing assignment. Others plugged away at a reading comprehension lesson, answering questions about an article they had read on conflict resolution. One child worked independently on a laptop.

The room was quiet enough that students were able to meet one-on-one with their teacher to discuss goals for an upcoming test. To a casual observer, it seemed like everything was running smoothly.

But Woods was not a casual observer. And simply having a classroom run smoothly wasn’t going to cut it at this school — not any more.

“We’ve got sixth graders at a third-grade level,” Woods said. “We need to take it up a notch.”

Woods’ school, Bethune Elementary-Middle School, was one of 38 in Michigan that were threatened with closure by the state last spring after years of rock-bottom test scores.

The schools on the closure list — including 24 in Detroit — were allowed to stay open only after their districts signed “partnership” agreements with state officials requiring the schools to boost their scores — and do so quickly — or face additional consequences.

What those consequences would be isn’t clear. The partnership agreements refer vaguely to the option to “consolidate or otherwise reconfigure” schools that don’t turn things around. But most observers suspect that schools like Bethune face shuttering if things don’t improve. Woods and her staff could be fired. And her students could face yet another disruption to lives that, in many cases, have already been rocked by violence, homelessness and other trials of poverty. All of Woods’ students — 100 percent — are from families whose incomes are at or below the federal poverty level, she said.

There are countless schools like Woods’ across the country that are staring down the threat of state or district intervention, struggling to get better results after years of falling short.

Whether Bethune will be one of the schools that manages to beat the odds and succeed remains to be seen, but observing what’s happening at Bethune offers a window into what schools like this are up against — and the tools they’re using to try to gain some ground.

“This is a heavy lift,” Woods said. “We’re dealing with things that are not always in our control, but … all I can say is, I have a lot of hope.”

* * *

Woods’ challenge is particularly daunting because she has to do two very difficult things in a very short period of time.

She must take a school full of children who are far behind their peers and get them caught up on material they should have learned years ago. That won’t be easy in a school where tracking tests show that roughly 90 percent of students are two or more grades behind where they should be in reading and math, Woods said.

And, at the same time, she must make sure they gain the skills and knowledge they’re expected to learn this year, in their current grade, even if that means working with fractions before mastering whole numbers or with paragraphs before mastering sentences.

Because regardless of why a child is behind, regardless of where the student previously attended school, regardless of whether family illness or unstable housing might have forced a child to miss too many days of class, and regardless of whatever else is going on at home, the state’s annual high-stakes M-STEP exam is the ultimate benchmark, and it won’t be impressed if a student jumps from say, a third-grade level to a fifth-grade level. If that student is in the sixth grade and isn’t doing sixth-grade work, he won’t get a passing score.

And if not enough students can leap over that grade-level threshold, then Bethune won’t meet partnership agreement targets that require the school to increase the number of students who can pass the M-STEP by 3.6 percentage points over the next two years.

That could be tough at a school where, last year, the percentage of students who passed the English Language Arts and Math exams in grades 3-8 was 0.6 percent — a handful of the 348 kids who were enrolled in those grades.

But more alarming than the threat of consequences from the state or district, Woods said, is the knowledge that if her students can’t reach grade level, they won’t be prepared for high school.

“It’s not about whether central office is watching. I don’t care,” Woods said. “It’s about our babies here. We want them to make progress.”

Woods says she’s determined to help each student accelerate two years this year.

“If our kids only grow one year, our kids will still be way behind,” she said. “We’ve got to speed it up.”

* * *

Many of the challenges facing Bethune are outside Woods’ control.

There’s nothing she can do, for example, about the fact that roughly half of her students are new to Bethune this year. Foreclosures, tax auctions, and other housing challenges in Detroit have conspired with school choice laws to create a culture in which families change schools frequently, hopping again and again between district and charter schools, even weeks or months into the school year. (Bethune’s turnover was worsened this year by the school’s return to the main Detroit school district after five years in a state-run recovery district. Among other things, the transition changed the rules about who could ride the school bus to Bethune.)

Though the school has a social worker, an attendance agent, and someone from the state Department of Health and Human Services to help families weather tumultuous home lives, there’s not much the school can do about the poor transportation or untreated health conditions that make it difficult for some kids to get to school every day.

More than a third of Bethune’s students — 36 percent — had missed more than two weeks of school by the end of November, enough to be characterized as “chronically absent” — and it hadn’t even snowed yet. Attendance at Detroit schools typically nosedives in the winter.

Woods also doesn’t have much control over who teaches at her school. Since many of her teachers from last year faced steep pay cuts when the school reverted to the main district this summer, many left. That meant Woods had to fill 19 of her 27 teaching positions over the summer. And she had to do so at a time when a severe teacher shortage was forcing schools across the city to scramble for educators.

She found enough teachers, but didn’t have the luxury of requiring them to do a model lesson or to go through a lengthy interview process to get hired.

“If you came in and you were certified,” she said, you pretty much got the job.

Woods can’t do much about class size, either. She considers herself lucky to have enough teachers for all of her classrooms, but a first grade class has 39 students. A third grade class has 41.

What Woods can control, she said, is what happens inside her classrooms. And that’s where she’s directing her attention.

“The focus for me has got to be on instruction. Period,” she said. “It can’t be anything else.”

So when Woods visited that sixth-grade classroom — taught by Samantha Vann, a second-year teacher who started at Bethune in September — she was looking for any possible way to maximize learning.

The boy on the laptop, she noted the next day when she met with Vann in her office, didn’t seem like he was focused enough while using an online learning program.

“He was just clicking on stuff,” Woods said. “We don’t have time like that to waste.”

The boy should instead be given a specific assignment based on the skills that tracking tests found lacking.

And while that reading comprehension lesson was interesting and the kids were clearly engaged with it — “It’s a great topic,” Woods said — she was concerned that the article the students were reading was too easy for sixth-graders.

“They need a little more rigor,” she told Vann.“Just because I’m not a great reader doesn’t mean I can’t comprehend [sixth-grade materials]. You still can teach the skill.”

Woods suggested that Vann replace the passage on conflict resolution, which had been taken from an elementary school teaching resource called K-5, with a passage from an old M-STEP exam.

“We just want to make sure we expose them to [the M-STEP] because if we wait until 30 days before the test, we’re in trouble,” Woods said.

* * *

Districts and states have long searched for silver bullets for improving schools: new academic programs, new technology, new grade configurations, even yoga and meditation. Many states have ramped up consequences for failing schools or have encouraged competition from charter schools in hopes that higher stakes would yield better results.

The partnership agreements, which are Michigan’s latest effort to turn around struggling schools, don’t have the teeth of earlier efforts, like last year’s aborted plan to shutter as many as 38 struggling schools across the state.

Gov. Rick Snyder turned to the agreements last spring when he took closings off the table after months of political pressure and lawsuits. But the decision angered GOP lawmakers who said the governor was ignoring a law he signed last year that required the state to shut down persistently low-performing schools in the city. (A new governor will be elected next year who could take a different approach).

Public school supporters embraced the partnership agreements, which were the brainchild of State Superintendent Brian Whiston, as a way to support schools rather than punish them. A state education department press release this week touts support schools have gotten with things like data analysis and improving school culture and climate.

But in Detroit, the support available to partnership schools is limited, just because the needs are so great. The state just added another 24 Detroit schools to the partnership agreement based on low scores in 2017. That means that 50 Detroit district schools — nearly half of the 106 schools in the district — are now subject to the agreement. And most of the other district schools are struggling as well.

So while Superintendent Nikolai Vitti says he’s ramping up support for all districts schools, those in the partnership program aren’t likely to get many extra services beyond some additional coaching for teachers and principals that’s being provided by Wayne RESA, the county intermediate school district. Vitti says partnership schools will be among the first to get new programs such as student mental health services, but there are no dedicated extra funds to help these schools.

For now, Woods says she’s relying on what she has. She has tracking tests to figure out which skills students need to learn. She has teachers’ aides and corps members from the City Year program, which places recent college grads in schools to work as tutors, to make sure that students get one-on-one or small-group time to work on academic deficits.

And she has devoted teachers who she tries to support, however she can. “You do a lot of informal observations,” she said. “You give a lot of feedback, making sure there are accountability measures in place, making sure teachers are teaching the curriculum and that they’re using their planning time to plan and do great instruction.”

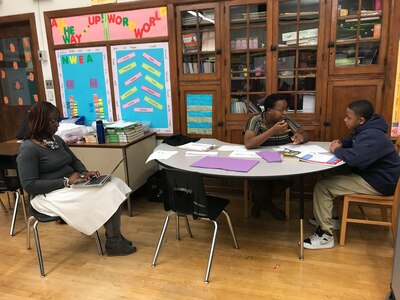

She sits in on classrooms, then brings the teachers into her office the following day to strategize about what’s working, and whether there’s anything they could be doing to move the needle on the M-STEP.

When she saw that a seventh-grade social studies teacher was asking students to give oral presentations on different countries, she asked if he could require the students to also write a report.

“The M-STEP is all writing and our blocks are 75 minutes. Are they really getting enough time in ELA to practice writing?” she asked the social studies teacher, Stephen Reynolds.

She urged him to grade students on not just what they write, but also to work with them on how to write.

“The next project, writing has got to take place for all of them because M-STEP is coming,” she said, and Bethune students can’t afford to wait until right before the test to start preparing. “Our kids are so far behind that they need to start this now.”

And while you’re at it, she asked Reynolds as they met in her office, could you possibly get the students to include math in their next presentation?

“I could,” Reynolds said. “Maybe some bar graphs?”

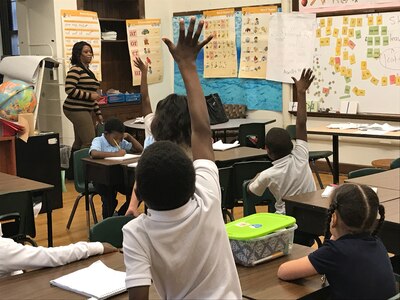

When Woods sat in on a second-grade reading lesson, she thought the students were connecting well with their teacher, Angela Willis, but she was concerned that Willis had called on the same student more than once.

“Be careful with that,” Woods cautioned when she met with Willis the next day. “You might not realize that you pick some of the same babies because sometimes we’re just moving so fast but … We need to really pay attention to are they responding to what we’re doing? … Who are the babies that are making progress, that are getting it? And who are the ones that … are still not getting it? We have to provide them with additional support.”

In every meeting with teachers, Woods said she asks them what they need and how she can help.

“You want people to feel good when they walk away and feel empowered to do the work because if they feel attacked, they can go make $7,000 more at the local charter school,” she said. “My thing is, I build people’s capacity. If you have a desire to teach, I’ll get you where you need to be.”

The teachers say they appreciate the feedback.

Vann said she hadn’t been sure how to find passages from the M-STEP before her meeting with the principal. Now, she said, she would hunt them down.

“I’m looking at my class through my eyes and I’m thinking it’s going smooth, but sometimes you can come in and see something,” Vann said. “If you notice something that I didn’t notice, I’m going to take your direction and then either try to fit it in or accommodate it any way.”

It can be daunting working with kids who have so many needs, said Reynolds, who is new to Bethune this year after working for 16 years in Detroit charter schools. But teaching is the best tool he has to help them, he said, so that’s where he’s focused.

“You will move the bar,” he said. “You just got to go in and do what you can.”

Woods isn’t promising fast, sweeping change at Bethune but she said she believes that things can improve for students.

“This is work that’s going to take a while, you know what I’m saying?” she said. “It won’t come overnight. But can it be done? Sure it can.”

Still, she added, “The problem is, you get new students and then they come with a different set of baggage. And then you start all over, so to speak.”