Add Mayor Mike Duggan to the list of people interested in grading schools in Detroit.

Even as state education officials are starting to measure schools using a 100-point scale, and as GOP lawmakers are pushing legislation that would assign A-F letter grades to every school in the state, Duggan announced in his State of the City Address Tuesday night that he, too, is looking for a way to measure city schools.

“Parents need to have information to choose their schools,” Duggan told a packed auditorium at Western International High School in southwest Detroit. “What if we got representation from Detroit Public Schools and charters, from the parent community, and academics, and we put out report cards that parents could rely on every year? And we did it together so parents had a basis for comparing?”

The report cards were one of several education initiatives that Duggan announced in his fifth state of the city address.

After largely steering clear of education in his first term, Duggan led off his nearly hour-long speech — the first state of the city of his second term — with several proposals related to schools.

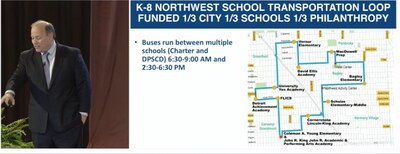

In addition to report cards, Duggan proposed testing out a new busing system that would serve students attending both district and charter schools.

The leaders of district and charter schools are notoriously combative in Detroit, fiercely competing against each other for students and teachers.

Previous efforts to get the two sides to collaborate have fizzled, including a $700,000, multi-year effort to get district and charter schools to use a single enrollment system.

But Duggan pitched an idea for a bus route — based on one that operates in Denver — that would travel a circuit in certain neighborhoods, doing pick-ups on designated street corners and dropping students off at both district and charter schools.

Liberal school policies in Michigan make it possible for Detroit students to attend potentially hundreds of schools in the city and surrounding communities, but many schools don’t provide bus transportation, putting school choice out of reach for many families.

In a city where a quarter of residents don’t have cars and where public transportation is woefully insufficient, some families make extreme sacrifices to access quality schools for their children.

The bus routes — which Duggan said would be funded one-third by philanthropy, one-third by the schools and one-third by the city — could even facilitate after-school programs that the schools on the bus route could work together to create, Duggan said.

“This is the concept we’re talking about,” Duggan said. “We’re shooting to get it done this fall. I don’t know if it’ll be six schools or 12 schools, but I can tell you from the enthusiasm [from schools] that if we could get DPSCD and the charters working together and collaborating, we could provide good choices right here in the city of Detroit and my role is going to be to support them, not to choose sides between them.”

Duggan said he brought district and charter school leaders together last week and they seemed game to work together.

“It was the most fascinating meeting,” he said. “It was almost historic. They’re getting along and I’ll show you why.”

Duggan then flashed a slide on the screen showing where Detroit children go to school: 51,000 students attend schools in the main district, 35,000 attend charter schools in the city and, Duggan said, “32,500 children got up this morning and went to school in the suburbs. That says that what we’re doing is not working …. It’s not working because we’re not working together. We’ve got lots of schools who are nearby who could share resources.”

The city plans to first roll out the bus system in northwest Detroit, Duggan said, and if it works, add additional routes across the city.

After many years of seeing Detroit schools controlled by state-appointed emergency managers, some Detroiters might be wary of mayoral involvement in the schools. It’s too early to say how well Duggan’s ideas will go over with educators and residents.

But he said his goal is to get people to work together, not to make anyone do anything.

“I’m not imposing myself on anybody,” he said.

Grading schools might be a controversial idea, especially considering that the city has many half-empty, low-performing schools. Some schools advocates might be worried that bad grades could be used as a basis to shutter some schools and allow others to stay open.

It’s also not clear that Detroit parents want a school grading system. A now-defunct nonprofit called Excellent Schools Detroit published school report cards for years using both test scores and other measures to grade schools. But few parents have used it.

Duggan, however, said when he pitched the report card idea to school leaders, they were on board.

“They said if the state gets behind it, we’d like to have you play that role,” Duggan said. “It was very interesting.”

Superintendent Nikolai Vitti introduced Duggan before the speech and returned to the stage afterward to hand the mayor a brick — a reference to people working together to build communities, each bringing their own brick.

“It’s about breaking down territorialism to do what’s right for children,” Vitti said.