The auditors’ findings were unsettling.

Middle schoolers in Detroit’s main school district have been taking pre-algebra classes that have “virtually no relationship” to the state’s mathematics standards.

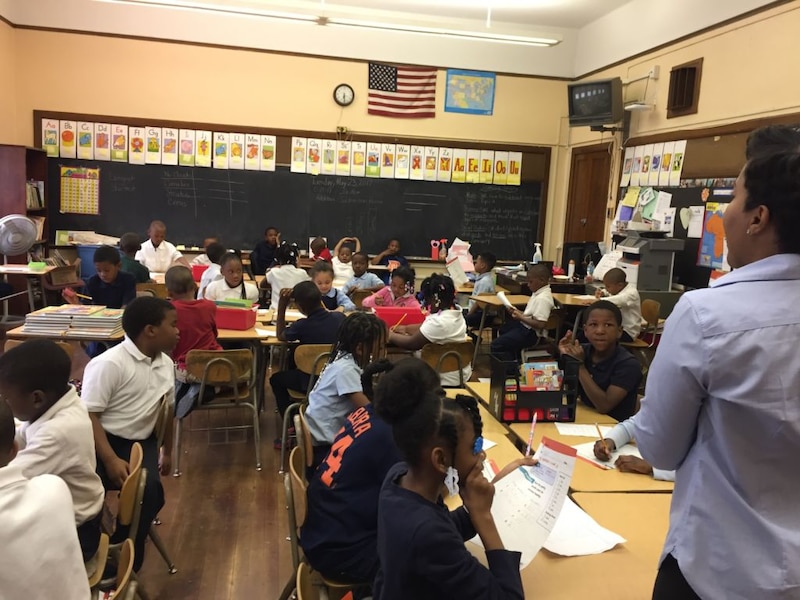

Students in kindergarten through third grade have been taught with an English curriculum so packed with unnecessary lessons that they don’t have time to get a firm grasp of foundational reading skills.

That “sets students up for a school career of frustration with anything that requires reading,” auditors found.

And an entire district of more than 50,000 students has been using textbooks that are so old and out of date that it’s likely that most students, for years, have been taking the state’s annual high-stakes exam without having seen much of the material they’re being tested on.

The test results can nonetheless be used to make potentially devastating decisions, like whether schools should be forced to close.

In short, the auditors who came to Detroit last fall to review the district’s curriculum found that students here have been set up to fail.

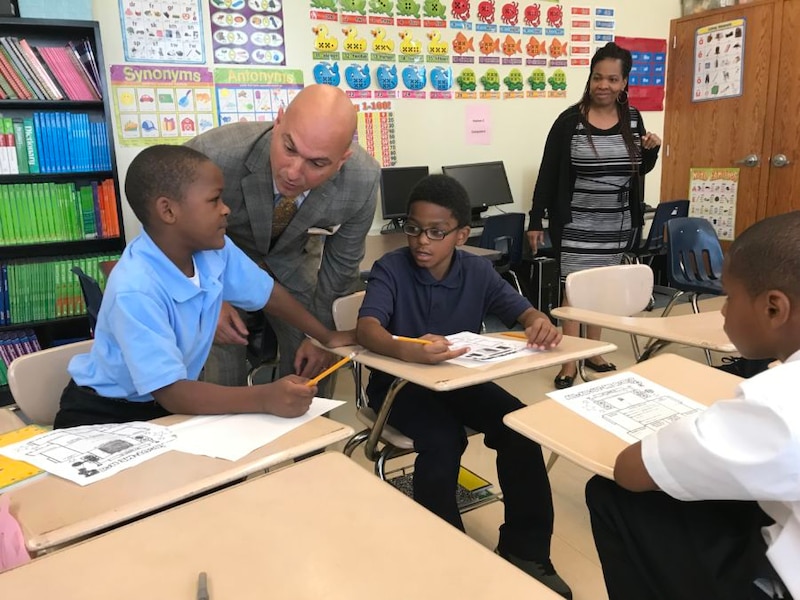

“It’s an injustice to the children of Detroit,” said Superintendent Nikolai Vitti.

But while this might sound like just another example of dysfunction in a long-troubled district, curriculum experts say that Detroit is among hundreds — possibly thousands — of districts across the country that are using textbooks and educational materials that are not aligned to state standards.

Detroit is now making a fix. The district plans to spend between $1 million and $3 million in the coming year to purchase new reading and math materials.

But most districts don’t do curriculum audits like Detroit has done. And curriculum experts say that most districts don’t realize the materials they’re using aren’t very good.

That means the students in those districts are not only ill-prepared for state exams, they’re less likely to succeed in college or careers.

“If you go to college and have to take remedial classes, that costs more money, takes more time and can ruin your life,” said Larry Singer, the CEO of Open-Up Resources, a nonprofit organization that makes quality math and English curriculums available to schools for free.

“If you can’t do algebra by the time you graduate from middle school, it’s very hard to finish up,” Singer said. “It takes 13 years to be prepared to be a freshman in college and every year that districts go with [improperly aligned curriculums], they sacrifice more kids to a difficult life.”

The fact that it has been years since Detroit teachers were given high-quality teaching materials is only one reason why students here have routinely posted some of the lowest test scores in the nation. Students face intense personal challenges in a city where more than half of children live in poverty. Their schools are dealing with a severe teacher shortage. And many buildings have deteriorated.

A curriculum overhaul won’t magically solve Detroit’s problems. But research suggests that even when nothing else changes — how teachers are trained or what challenges students face at home, for example — higher-quality curriculum materials can raise student learning.

And student learning urgently needs to improve in Detroit, teachers say.

“Their reading skills are so low,” said Faith Fells, a history teacher at Detroit’s Mumford High School who returned to the city this year after teaching in Boston. “I thought some of my students last year were struggling and some of them were reading and writing below grade level. But here I would say it’s the vast majority of our students.”

Auditors reviewing Detroit’s curriculum last fall found that most of the materials used in Detroit schools are from 2007 or 2008, before the state’s current standards were adopted.

The state of Michigan took over the district in 2009 and appointed a series of emergency managers who ran the city schools until last year. The emergency managers apparently never made updating text books a priority.

“The emergency managers were focused on closing schools, budget issues and those kinds of things,” said Randy Liepa, the superintendent of the Wayne County intermediate school district, which supports Wayne County districts including Detroit and helped find about $40,000 in federal money to pay for Detroit’s curriculum audit. “It seems like clearly the curriculum wasn’t being addressed.”

The problem became more acute when Michigan joined 44 other states in adopting the Common Core standards in 2010. Those standards were meant to help states ensure that students would be prepared for college-level work upon graduation. Their adoption rendered old curriculum materials immediately out-of-date — and also spurred criticism that the federal government, which had encouraged states to adopt the standards, had reached too far into states’ purview.

The ensuing tumult has made state officials hesitant to get involved in what is taught in local classrooms, Singer said.

“Once upon a time, states had a very strong role in selecting curriculum,” Singer said, estimating that, five or six years ago, roughly half the states in the country would bring educators together every year to review textbooks and materials and make recommendations to school districts. The states would often provide financial incentives that encouraged districts to choose from the state’s recommended list.

Today, he said, nearly every state leaves those decisions exclusively to local districts, which may or may not have the staff and resources to fully vet the claims of textbook publishers.

“A lot of districts just rely on what vendors tell them,” Vitti said. “[Publishers say], ‘Of course it’s aligned to the new standards.’ They even put on the front cover of the books ‘Aligned to Common Core standards’ but there hasn’t been a lot of time spent unpacking whether that’s really aligned or not.”

The state of Michigan does not track what curriculum materials are being used in local schools. A spokesman for the Michigan Department of Education said it has no way of knowing how many of the state’s more than 500 districts and 300 charter schools are using materials aligned to the standards.

“The MDE doesn’t dictate or track local curricula, or alignment with our state standards,” William DiSessa, a department spokesman, wrote in a statement. “This is a local education state and we’re not charged with doing so.”

People who have paid close attention to curriculum across the country say the result is curriculum materials that often do not reflect what students are expected to know.

“It’s far too common” for districts to be using poorly aligned materials, said Eric Hirsch who heads an organization called EdReports that’s like a Consumer Reports for curriculum. The three-year-old non-profit brings expert educators from around the country together to review curriculums.

Of the first 197 math programs EdReports reviewed, just 48 met the organization’s criteria for alignment. Of the first 111 English Language Arts curriculums EdReports reviewed, just 58 met the organization’s criteria.

Many teachers know they’re not using great materials, Hirsch said, noting that a recent survey of teachers found that only a fraction of teachers — fewer than 1 in 5 — believed the materials they were given by their districts were aligned with state standards.

Instead of relying on those textbooks, he said, teachers spend an average of 12 hours a week searching for lesson plans on the internet.

“They’re on places like Pinterest and Google, which are not curated,” he said. “It’s hard for a teacher who has probably 150 kids to do that level of work.”

That story rings true for Nicole Cato, a ninth-grade English teacher at Detroit’s Mumford High School who returned to the district this year after four years in a suburban school. “I spend a lot of time looking for additional resources,” Cato said. “All of my prep periods, plus the weekends.”

After the audit, district officials are eager to send help Cato’s way. The audit, which was conducted by New York’s Student Achievement Partners, a nonprofit organization whose founders include some of the people who wrote the Common Core standards, awarded the district’s English curriculum 3 out of 21 possible points.

The math curriculum fared even worse. It got zero points.

Sonya Mays, a member of the Detroit school board, which resumed control of the district in January 2017, described the results as “chilling” when they were presented to the board last month.

Now, she said she’s hopeful that the audit can lead to better things.

“As outraged as I am,” Mays said, “the silver lining is it’s really, really hard to make a case that something doesn’t need to change quickly and drastically.”

Curriculum is a relatively easy fix. Buying new materials is significantly less expensive and more practical than lowering class size — especially in a district that already has nearly 200 teacher vacancies.

A quality curriculum is also especially important in cities such as Detroit where the vast majority of students are growing up in homes where they’re less likely to have access to books and less likely to hear the kind of expansive vocabularies that more affluent children do.

“A lot of our kids are entering kindergarten already behind, their vocabulary exposure, their background knowledge, their recognition of letters and sounds,” Vitti said.

If their teachers are well-prepared with a quality curriculum, it can be an equalizer that will put Detroit students on even footing with their peers in the suburbs, he said.

The district is now soliciting bids for a new curriculum that will be used across the district next year.

A team of teachers will review the options, making sure materials meet the needs of special education students and those who are learning English, and that they’re culturally sensitive, meaning students will see pictures and read stories about people who look like them. They’ll consider cost — the district is budgeting between $1 million and $3 million a year for curriculum , Vitti said — and factor in things like whether the materials are user-friendly.

But this much is sure, Vitti said. “Regardless of how nice, how user-friendly the materials are, if they’re not highly aligned to the standards, then they won’t move on.”

The district will select the curriculum later this spring and start to train teachers on it for next year. The process could be difficult, Vitti said. Students might struggle with suddenly being asked to do work for which they haven’t been fully prepared in prior years. But it’s something that district is going to have to go through, he said.

Cato, the Mumford English teacher, said she looks forward to having top-notch instructional materials to use with her students next year — even if she might still supplement with things she finds online.

“Teachers need at least a game plan and a curriculum provides that,” she said.

Read the audits of Detroit’s math and English curriculum below: