Roughly once a week for much of the school year, 14 children have been gathering at the Spring Creek Equestrian Center in the western Michigan town of Three Oaks to learn about caring for horses.

“They clean the stalls, groom them, feed them … they learn the mechanics of the horse, how you care for them,” said stable owner Alison Grosse. “It’s not just a fun activity. It’s a whole experience.”

And the best part? Aside from a $40 riding fee that families contribute, the program is completely free for participants, paid for by the state of Michigan through a program called “shared time” that allows private school and homeschool students to take free classes through their local school district.

In a state where vouchers are illegal because the state Constitution bans the use of public dollars for private schools, Michigan lawmakers — including some who are closely allied with U.S. Education Secretary Betsy DeVos — have taken steps in recent years to dramatically expand the shared time program as a legal way to use public dollars to serve students in non-public schools.

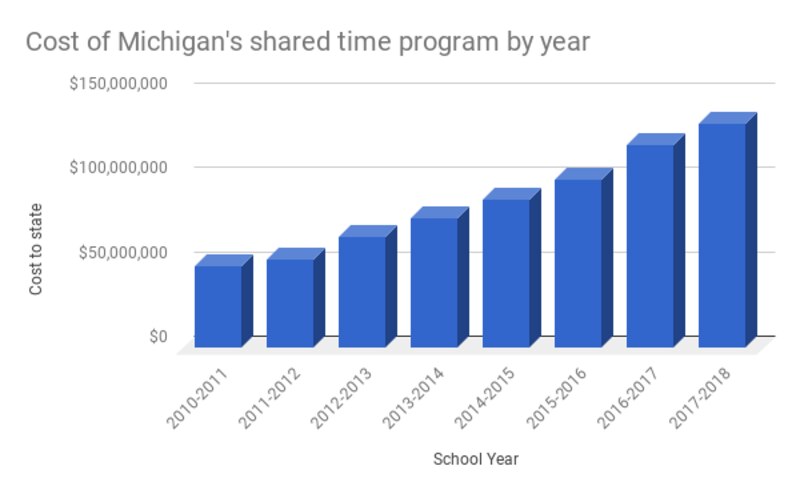

The result is a program that has nearly tripled in size in the last seven years, with state costs ballooning from $48 million in 2011 to more than $133 million this school year.

The program has gotten so big — and has claimed such a sizable chunk of the state’s education budget — that Gov. Rick Snyder, a Republican who had been supportive of the program in the past, now says it’s gotten out of hand.

He questions the courses some districts are offering — including one that takes students on a state-funded wilderness adventure, and another that teaches students to play Minecraft. And he’s raised concerns about a growing number of districts that now offer so many shared time courses that they’ve essentially added thousands of students to their rosters and are raking in far more funding than districts of a similar size.

Some Michigan districts are getting paid 20 or 30 percent more from the state than they would without shared time, state data show. One charter school that offers shared time programs has essentially doubled its share of state education dollars. (Scroll down for a list of districts that are heavily relying on shared time).

National education experts say the arrangement — which currently serves more than 100,000 private school and homeschool students across the state — is highly unusual. Most states either embrace the use of private school vouchers that let families use taxpayer funds to cover private tuition, or generally keep public and private schools separate, said Micah Ann Wixom, a policy analyst with the Education Commission of the States, which tracks education policy across the country. “In my experience, most school districts have clear delineation between public and private.”

Snyder is not opposed to the shared time program itself but says that it’s gone beyond its original intent.

“This program diverts resources from core instruction that improves student outcomes,” Snyder asserted in the proposed budget he released in February.

Snyder’s budget proposal, which is now being negotiated with the legislature, would put restrictions on the number of shared time classes a district could offer, prohibiting districts from collecting state funds for shared time that go above 5 percent of what they’re receiving for their public school students. Snyder also wants to end shared time classes for kindergarteners.

Snyder says those reforms would generate an estimated $68 million that he wants to distribute to schools around the state. The cuts to shared time are part of how he proposes to raise the per pupil funding schools receive next year by $240 per student.

The proposed cuts have faced sharp opposition from lawmakers who support giving parents options other than their local public school. Some of those lawmakers are allies of DeVos, a Michigan philanthropist who has long led the fight for vouchers in her home state.

“I don’t plan to go along with [cuts to shared time],” said Rep. Tim Kelly, a Republican who leads the House education committee that expects to take up the budget when it returns from spring recess later this month. “This is a public school working for more families. It’s a way to bring in formerly homeschooled kids on their terms. It is, plain and simple, a taxpayer getting a benefit from a public entity. Who is getting hurt?”

Kelly said he has a plan to raise per pupil funding by the same $240 per student that Snyder has proposed without cutting shared time, though he declined to say what he would cut instead.

The state Senate is more open to putting some restrictions on shared time. A budget bill that passed out of the Senate education committee last month would end shared time for kindergarten and impose some new quality controls on the program, but the Senate has no plans to significantly curtail shared time, said Sen. Phil Pavlov, the Republican chair of the Senate education committee.

“We want to make sure that it’s quality programming,” he said, but added: “Shared time has been probably one of the most successful programs we’ve been able to come up with. It really exemplifies choice and opportunity for students to non-core learning opportunities and local traditional school districts benefit from it … I don’t think we should be putting limits on it.”

* * *

The shared time program began decades ago as a way for private school or homeschooled students to take non-core classes including gym, art, or music from their local public school.

Over the years, the program has evolved so that districts now bring the programs to private schools. Most shared time teachers today are public school employees who work inside private schools, teaching private school students in private school classrooms.

Some, like Grosse, who runs the equestrian program through the Berrien Springs district in western Michigan, are teaching courses created for homeschooled schools. Some districts are offering virtual shared time classes that allow students to learn a number of subjects — from computers to agriculture to dance — without leaving their homes.

Michigan courts have found the arrangement to be legal because it doesn’t involve the direct spending of public dollars in private schools. Rather, public schools hire instructors, then receive funding from the state based on the number of hours students are in shared time classes. As those hours add up to the equivalent of full time students, the district gets the same per pupil funding — about $7,700 per student, on average — for shared time students as it does for traditional students. (Districts in Michigan get different amounts per student based on historical funding levels).

The arrangement works well for the school districts that sponsor these programs.

“Rather than cut band, orchestra, choir, academics or cut counselors, shared time was a way to say, ‘look, we can create partnerships with some of these other schools, and that will help the kids in our district,’” said Dennis McDavid, the superintendent of Berkley schools.

The small affluent district in the northern Detroit suburbs currently offers so many classes in private schools, offering potentially dozens of courses, that student class hours this year added up to the equivalent of nearly 1,500 full time students.

That means that Berkley, a 4,300-student district that gets $8,123 per student from the state, takes in an extra $12 million a year from the state through shared time. That’s a lot of money for a district whose budget McDavid put at around $55 million.

To be sure, the district has expenses related to shared time. It has to recruit, train, and supervise teachers at about 40 different private schools, but those contracted teachers are paid less than the unionized teachers who teach in Berkley schools. McDavid said the district gets to keep about 35 to 40 cents on the dollar that it brings in from the program.

Shared time works well for private schools, which can offer a range of extra classes to their students without having to raise tuition.

“The benefits have been wonderful,” said Fayzeh Madani, the principal of the Michigan Islamic Academy in Ann Arbor, which has used Berkley teachers in recent years to offer gym, computing and art.

“They’re providing us with instructors for some of the courses that we would maybe not have if it weren’t for shared time,” Madani said, adding that her school serves many low-income families who would not be able to pay much more in tuition.

And it works well for homeschoolers who can take advantage of free programs that wouldn’t otherwise be available to them.

Those are some of the arguments that have led to the recent legislative changes that have encouraged the growth of the program.

Originally, districts were only allowed to provide shared time services to students at private schools within their district boundaries. But in recent years the law has been amended several times. First, lawmakers made it possible for districts to serve private schools in neighboring districts. Then they made it possible for districts to serve schools throughout their county. Then they allowed districts to offer services to schools in neighboring counties.

Last year, the law was amended yet again to allow kindergarten students to participate.

That’s why Berkley kept investing in shared time, McDavid said. “All the signals from Lansing were, ‘This is great. Keep it up.’ because they kept expanding the availability of partners.”

Snyder himself has signed off on expansions of the program, McDavid said.

“It’s puzzling and sort of surprising to a lot of us that this governor, who was in favor of it and had a hand in expanding it, is now making a pretty draconian shift away from expansion. It looks to me like he’s trying to kill it.”

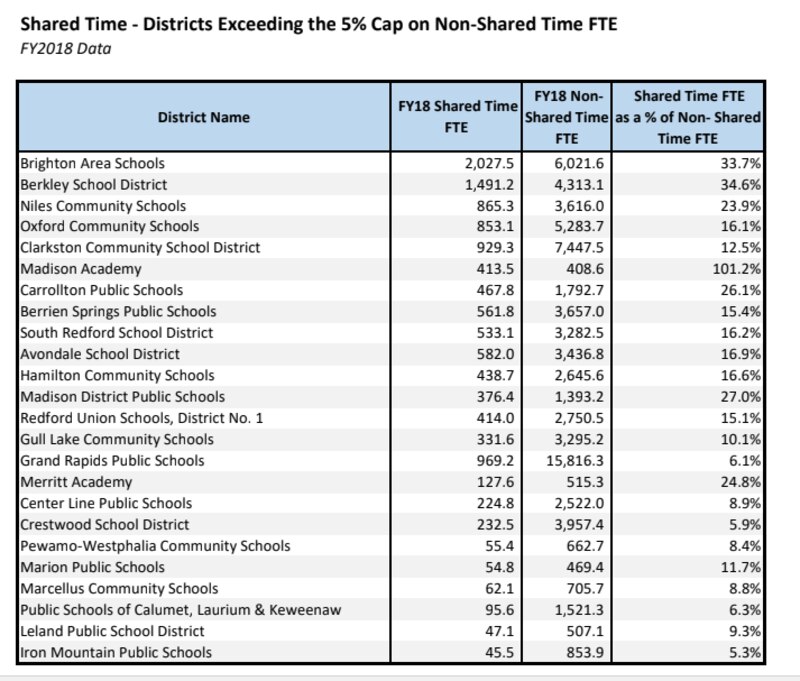

Snyder says he’s not trying to kill shared time, just rein it in. He notes that only 24 districts in a state with more than 500 districts and 300 charter schools are currently exceeding the 5 percent cap that he wants to impose. He argues that kindergarten shouldn’t be included in shared time because it’s harder to determine what constitutes “core curriculum” in a classroom where art and music are an integral part of instruction. Kindergarten is also not required in Michigan.

But for those 24 districts, the changes would be painful.

“It would hurt us tremendously,” McDavid said.

Other districts that would be deeply affected include Brighton Area schools, which gets a 34 percent boost from shared time. The Madison Academy charter school in Flint gets a 101.2 percent boost, offering shared time services to the equivalent of 414 students while running a school for 408 students.

Snyder’s budget director, John Walsh, said he is sympathetic to the plight of districts like Berkley that have come to rely on shared time funding, but he says the program needs an overhaul.

“While these offerings are certainly educational, our position is that much of the programming has evolved too far away from the original intent and vision,” Walsh said in a statement. “I believe that our recommendation is based on the right thinking to ensure that our educational dollars are spent in the most effective manner possible to support the goal of improving student outcomes.”

In addition to putting limits on the number of shared time students a district can serve, Snyder’s budget would require districts to provide details to the state about the courses they’re offering.

Craig Thiel, the research director at the nonpartisan Citizens Research Council, which has been ringing alarms about the shared time expansion, says additional oversight could help the state better define what constitutes “core” courses.

Currently, he said, some districts are offering Advanced Placement classes through shared time that are technically non-core because they’re electives. But AP English, AP History and other similar classes can be used by high school students to fulfill core graduation requirements.

Other districts, he said, might not be complying with rules that require districts only to offer shared time courses that are also available to their own students. The horseback riding class in Spring Creek, for example, takes place during the school day, making it difficult for traditional students to attend.

“A lot of the growth has occurred because of very little direction by the Department of Education,” Thiel said. “They knew it was controversial and just punted on this,” allowing the county school districts that support local districts to decide “whether or not shared time programs meet the letter of the law.”

William DiSessa, a spokesman for the state education department, said the state conducts quality control reviews to make sure districts are complying with state law. But, he said, districts have the right to decide what classes they want to offer.

“Locals are the experts on their student body and the programs they elect to offer,” DiSessa said in a statement. “This level of autonomy also allows for innovation and novelty in the types of educational services offered.”

Thiel, however, says the fact that so many districts have turned to shared time as a way to balance their budget speaks to larger problems with the way schools in Michigan are funded.

“That’s a signal that our school funding system is broken,” he said.

These are the districts that are benefiting the most from the shared time program: