Throughout the Mumford Academy High School one morning this month, teachers were prepping their students for upcoming SAT exams. Teens flooded the hallways between classes, calling out to friends.

But for much of this day in early April, the school’s principal, Nir Saar, was isolated from the usual rush and noise of his northwest Detroit school. He was instead in a small conference room beyond the main office, huddling with his top advisors and a team of education experts in hopes of solving a problem that some say imperils the ability of schools in Detroit to be truly successful.

The problem is this: Because so many schools in Detroit are struggling, and so many are turning out grads who are ill-equipped to succeed in college, many Detroit educators have never had the chance to work in a high-performing school.

They’ve never seen an effective force of well-supported teachers working together to meet students’ needs and see them succeed.

That’s the impetus behind the new $900,000 Team Fellows Program, funded by the Detroit Children’s Fund, that kicked off earlier this year at the Mumford Academy and at two Detroit charter schools.

The program brings advisors into Detroit schools to provide intensive coaching to principals, assistant principals, deans and other top administrators. The coaches work with school leaders together as a team to collectively create improvement plans, then work to implement them.

The Children’s Fund sees the Team Fellows program as a model that could be expanded across the city. But it has already hit an early hiccup with the news that Mumford Academy is likely merging with the larger Mumford High School. The uncertainty underscores the challenges Detroit school advocates have grappled with for years, as promising programs have begun in schools that closed or were wiped out by changes in management.

Still, supporters are hopeful the concept is strong enough to weather the uncertainty.

Jack Elsey, who launched the program last year after becoming the first executive director of the Children’s Fund, said his goal is to bring strategies that have been successful in other cities to some of the more promising schools in Detroit.

“There are a whole set of best practices that happen sort of repeatedly, almost without thinking, in high-performing schools,” said Elsey, who has worked as a New York City teacher, and as a top school administrator in the main Detroit district, the Chicago Public Schools and in Detroit’s state-run Education Achievement Authority.

“At a foundational level, all high-performing schools have a clear vision for what they want to achieve,” Elsey said. “They’re constantly assessing themselves and having others assess them. … The Team Fellows is designed to provide those reflective moments.”

Cutting shadow missions

The coaches from a New York-based organization called the School Empowerment Network, which got its start helping to launch 121 new schools in New York City, first came to the Mumford Academy in January. They met with students and educators, grilling them about what was working and what needed to improve.

They then set some ambitious goals. Among them: making sure teachers are adopting an “instructional vision” that involves pushing students not just to learn information, but to think about and discuss what they’ve learned.

The team set a goal that 80 percent of current 11th graders would score a 980 on the SAT by 2019, with at least 30 percent scoring at least a 1060 — numbers that would put the school well ahead of the curve in a city where the average SAT score last year was 887 and the statewide average was 1007.

A third goal involves increasing student involvement in school-wide activities by 40 percent — an effort the team and its coaches hope will improve relationships between students and reduce the percentage of students fighting or getting into trouble.

The group then mapped out a long list of action steps that Saar and his team agreed to implement. Their coaches come to Detroit every other week to keep them on task, and will be leading the team on a trip to New York City to tour three schools that the coaches consider models for success. Included on the tour are a charter high school, a small district high school inside a large Manhattan campus, and an unusual K-12 school that uses a project-based curriculum.

On that April morning in the conference room, the Mumford Academy leaders were discussing different ways to observe teachers, and to build “data dashboards” that track everything from student discipline to attendance at after-school events.

They discussed ways to cut down on what they call “shadow missions,” meaning work that takes them away from their priorities. They grappled, for example, with whether the principal and his top advisers should staff lunchtime detention for students who’ve broken school rules.

“You’re wanting to show that you’re willing to be in the trenches and do that work,” Saar said, adding that lunch detention is also a quiet time when he can get other work done.

But if Saar or his assistant principal are watching students during detention, or keeping peace in the cafeteria, they can’t attend teacher planning meetings that take place at the same time — meetings that could be key to promoting the school’s instructional vision.

The group then discussed strategies like developing a rotation so one administrator per day could peel off from lunch duty to work with teachers.

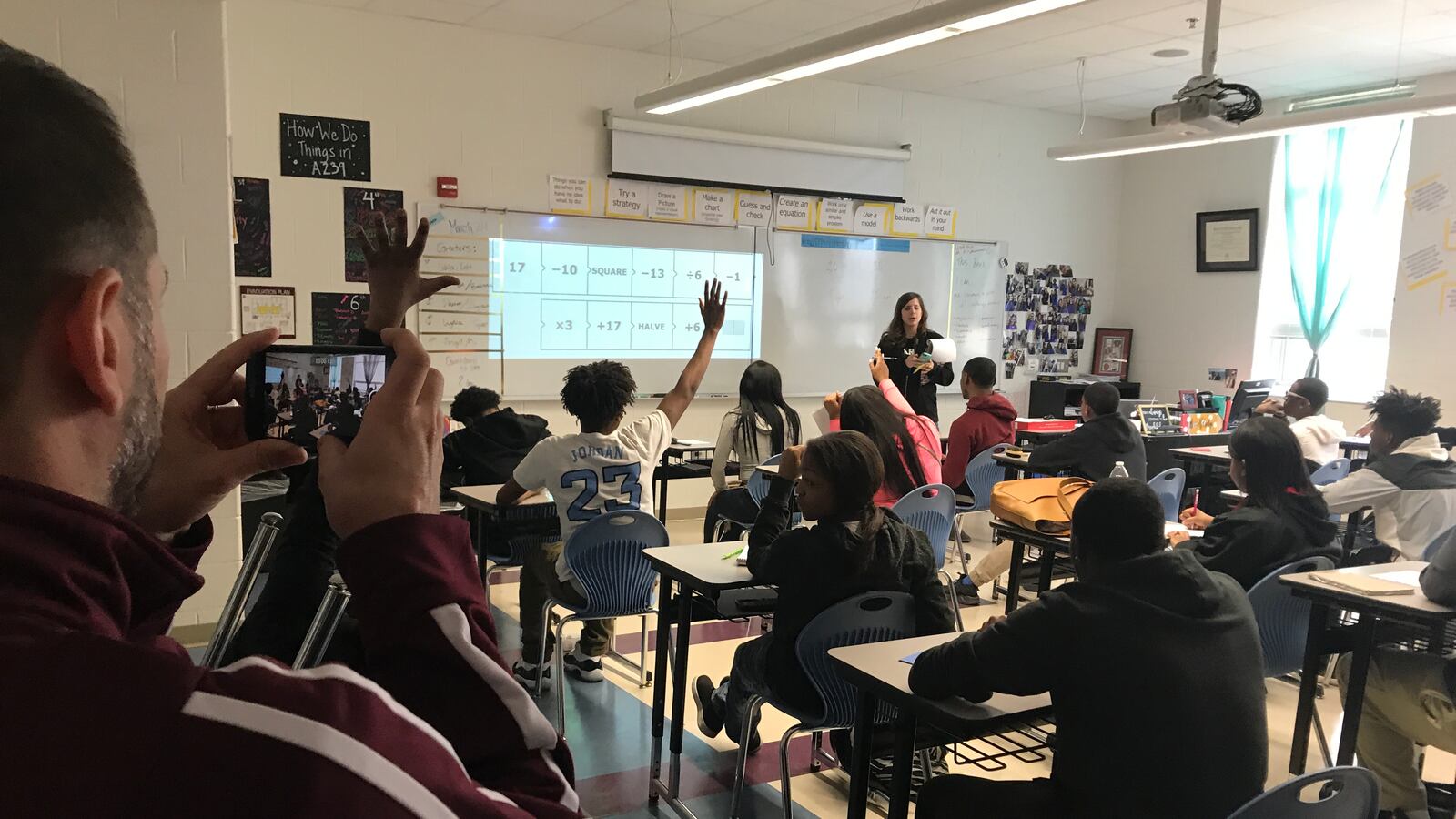

Also in the works that morning was a plan to capture Mumford Academy educators during moments of great teaching to show other teachers how it’s done.

One of the team’s coaches, Carrmilla Young, a Detroit native who has worked in schools in Texas, Chicago and Fresno, California, offered to help locate videos that demonstrate great teaching. But Saar said he preferred to produce them in the school.

“You know how it is,” he said, “when you see your kids and all of that, you rule out all the ‘Oh, these are white kids in the suburbs. They have 15 kids in the class.’ All of that stuff. So I think we definitely should make a commitment to try to keep it in house.”

He said he and his leadership team would commit to capturing as many videos as they could on their phones so the group could watch them with their coaches to identify moments that would be useful for other teachers.

“We almost need a catalog,” Saar said, “where it’s like, in video one, we can highlight these things … If we get to a really good place, three years down the road, I’d love to have the time signatures so it’s like at a minute-fifteen, we see this element that’s really effective.”

That way, he said, teachers who are struggling with, say, classroom management, could be directed to a certain moment that was captured in a colleague’s classroom.

“That’s a really high level of functioning that I think we eventually will get to,” Saar said.

Will instability interfere?

The Team Fellows program is one of several that the Children’s Fund is kicking off in Detroit this year.

The Fund, which is affiliated with the Skillman Foundation (a Chalkbeat funder), has a stated goal of creating 25,000 high-quality school seats in Detroit by 2025. That would be a major improvement in a city where Elsey estimates that just 8,000 Detroit children currently have access to high-quality schools — a tiny fraction of the more than 100,000 school-aged children in the city.

His organization is heavily focused on training educators. In addition to the Team Fellows program, which works only with teams of leaders currently working together, the fund is now inviting educators to apply for a new Leaders Institute that will train teams of educators to take control of new or existing schools.

For the Team Fellows program, Elsey said leaders from 25 Detroit district and charter schools applied to be part of the program, which was targeted to schools the fund considered “good schools” that could become “great schools” with a little extra support.

The two charter schools that were selected are part of the same network — the Detroit Achievement Academy in northwest Detroit and its newer, sister school, Detroit Prep in Indian Village. The schools selected all had strong track records with test scores, attendance rates and other measures of school quality.

Mumford Academy, a small school that launched with just ninth-graders inside the larger Mumford High School in 2015 when the school was a part of the Education Achievement Authority, was selected last winter before the school’s future was called into doubt.

In March, Detroit Superintendent Nikolai Vitti recommended to the school board that all buildings containing more than one school be merged to save money. That means the Mumford Academy, which now has students in grades 9-11 will likely join with the larger Mumford High School in September. It’s not yet clear who will lead the newly merged school, but Vitti said he sees no reason why the Team Fellows program can’t continue at Mumford.

“If the focus is on supporting children, then they will still be there,” he said. “Just under one school, not two.”

The program was designed to continue through the 2018-19 school year but the merger could mean that Saar and his team could be split up. They might not all be selected to be a part of the new school leadership team, or they might decide to leave.

Elsey said the fund will make decisions when more information is available. After years working in Detroit schools, he said, he’s come to expect perennial change.

“Look, when you do this work, you have to be flexible with the dynamism that exists in today’s urban schools,” he said. “If there’s a way we can continue to believe and see that this program could be helpful at Mumford, then we’re committed to find a way to do that. We’re going to keep watching it.”

That “dynamism” in Detroit schools — usually described with less positive words like ‘instability’ — is one of the things that makes improving schools more difficult in Detroit than elsewhere, Young said.

Mumford alone has, since 2011, been added to the state recovery district and returned to the main Detroit district when the recovery district dissolved. It was put on a state list last year of schools in danger of being shut down. It saw the Mumford Academy created by one set of administrators, and now it faces a merger promoted by another.

“Every district has some variation of that,” Young said. “But it seems like it’s been prevalent in Detroit for a few years now.”

Still, Young said, the benefits of the Team Fellows program will continue no matter what happens to the school.

“A solid instructional vision is important, whether you’ve got 300 kids or you’ve got a whole high school full of them,” she said.

Jessica Westermann, an executive director at the School Empowerment Network and one of the coaches working at the Mumford Academy, noted that Detroit schools have far fewer resources than schools in New York City, where she has spent the bulk of her career.

But that doesn’t mean that the New York team can’t spot ways to help Detroit educators step up their game.

“We can’t bring higher per-pupil funding,” she said. “But I do think there are ways of doing more with the resources you have, of taking the people who are working together, and making sure that they are working in an aligned fashion.”

Saar said the lessons he’s learning will be valuable no matter where he ends up.

“For me as a principal who is often running around doing 20 million different things, this has been a very focusing kind of experience,” Saar said. “It’s really forced us to step back to ask, ‘What is it we actually want a high-quality school to look like?’… It’s not something we spend a lot of time thinking about, but it’s been really nice to have somebody from the outside come and ask those questions.”