Detroit is not the only district struggling with lower enrollment and other challenges related to competition from charter schools and surrounding districts. On the other side of the state, similar forces led to the Albion school district’s demise.

After years of declining enrollment, falling revenue, poor student performance and school closures in the district, the Albion district in western Michigan faced a difficult problem: How to keep the district from dying. The city of Albion had a large number of students, but many of them travelled outside the city to attend school, forcing the Albion Community Schools district to merge with nearby Marshall Public Schools in July 2016.

Albion’s story was one of many shared Monday with state’s Civil Rights Commission, which held its first in a series of public hearings Monday in Ypsilanti to hear firsthand about issues confronting school districts. Representatives from public policy organizations, school districts, as well as parents, educators and advocates from Detroit and around the state shared stories of hardships and difficult decisions they face.

The commission is charged by the state’s constitution with investigating alleged discrimination. It launched the hearings this week after learning from education experts that state schools are in crisis. The goal of the hearings is to determine if minority students and those with special needs have faced discrimination in the state’s schools.

Albion’s story came from Randall Davis, superintendent of the Albion-Marshall School District, who told commissioners he blamed what happened to Albion schools — a district that had primarily served low-income, African-American students — on a law passed more than two decades ago that allowed students in Michigan to attend any school in any district that would take them.

“Schools of choice decimated the schools,” Davis said. “They had three or four of our contiguous districts that were driving into their district picking kids up. It was active and aggressive….I believe that is not the intention of schools of choice, but that’s what happened.”

The hearing was not intended to focus on competition from charter schools and between neighboring districts, but many of the people who testified came from traditional district schools or from policy organizations, so much of the testimony centered on the consequences of choice in Michigan.

Individuals also came forward to raise various concerns about equity in schools. The commission did not hear from charter school advocates but the commission plans to hold at least two other hearings.

“We also open it up to anyone to offer their opinions,” said Vicki Levengood, communications director for the Michigan Department of Civil Rights. “We encourage people on all sides to bring their messages to the hearings.”

The next hearing will be July 23 but a location has not yet been set, she said.

At the first hearing Monday, Benjamin Edmondson, Superintendent of Ypsilanti Community School District, painted the grim, poignant picture confronting him when he became the district’s school chief in 2015.

The Ypsilanti district lacked money to pay for services students needed such as social workers, homeless services, school safety officers, and washers and dryers. The district only managed to provide those services by partnering with the University of Michigan, Eastern Michigan University and community colleges.

“Those partnerships are critical,” he said. “I don’t know how we would survive without those entities buying into the district.”

Edmondson said his district had lost 300 students before he arrived, costing the district nearly $2.4 million. That forced him to scrap advanced placement classes and meant he couldn’t pay teachers enough to fully staff his classrooms. Graduation rates were low and the district was swimming in debt. The district’s challenges were compounded by the fact it competes with the nearby Plymouth-Canton Community Schools district, which enrolls more than 17,000 students. “We were David and Goliath,” he said.

The district also faces a “strong charter school presence,” he said, recalling a charter school representative who came vying to purchase a vacant district building. He said he felt threatened by the potential buyer’s ability to automatically take 300 students from the district.

“Here I am a new superintendent with a new school board and I just want to paint the story,” he said. “In 2015, we had declining enrollment, white flight, poverty, low expectations, low wages, high debts and priority schools, neighboring charter schools, and a state takeover threat for our schools.”

This year, Edmondson said the district is improving but still facing daunting challenges.

With population declines and fewer students in districts, even with consolidated districts, Michigan’s districts are too small, Eric Lupher of the Citizens Research Council of Michigan told commissioners. He said it means school districts from around the state are struggling because they are losing so many students to surrounding districts.

For example, he said Ypsilanti Community School District is continuing to bleed students to Ann Arbor, Plymouth-Canton and other districts. Ferndale schools are gaining almost 800 students from Oak Park and Detroit schools, but is losing about 350 students to districts further from city line such as Royal Oak and Berkley schools.

The issue isn’t limited just to southeastern Michigan, he said, pointing to Wyoming Public school district, about five miles from Grand Rapids, which has lost students to nearby Jenison and Grand Rapids.

“It’s a bigger issue, and it’s a lot bigger than just consolidation,” he said. “It’s the choice we’ve offered. I’m not here to speak ill of choice, but it’s creating issues we’re not dealing with.”

The eight commissioners listened intently through the six-hour hearing at the Eagle Crest Conference Center, Ann Arbor Marriott in Ypsilanti, occasionally asking questions.

Commissioner Jeffrey Sakwa at one point expressed sympathy for the superintendents. “You guys are in a tough place,” he said.

While Michigan once had nearly 600 school districts, Sakwa said, that number is shrinking.

Sakwa blamed competing school districts as a primary reason for the changes.

“It’s like Burger King, McDonald’s, and Kentucky Fried Chicken all on the corner trying to steal everybody’s lunch every single day,” he said.

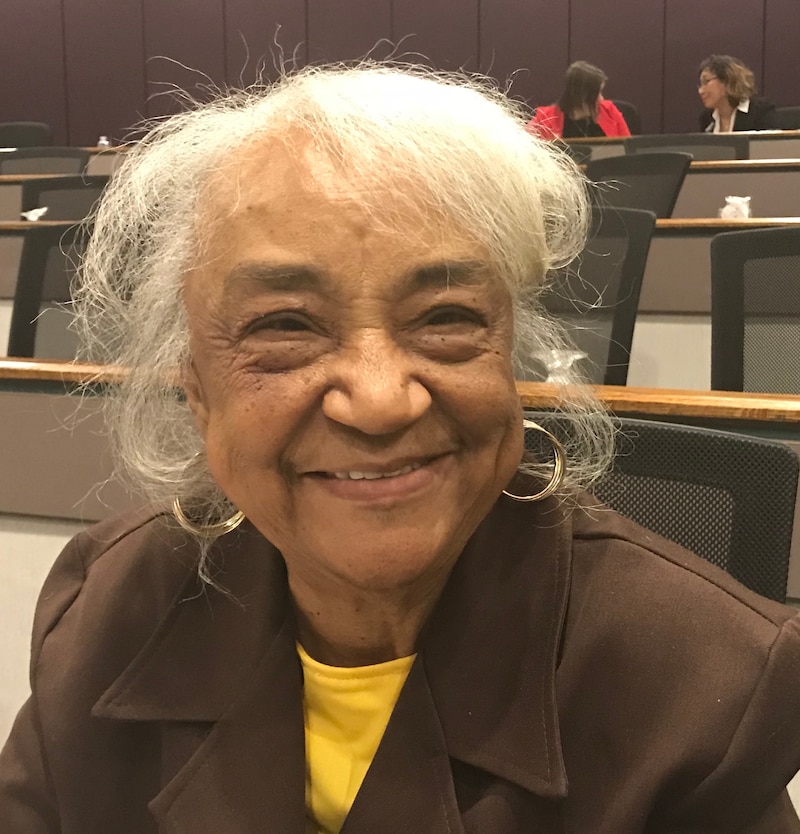

About 20 people from Detroit, Ypsilanti and Ann Arbor spoke during the public comments portion of the hearing. Among them was longtime Detroit education advocate Helen Moore. “Don’t play games with us,” she told commissioners over applause that sometimes drowned her words.

“You know the discrimination we have received as black people and our children. You know that during slavery it was against the law to read. This is what’s happening to our children now.”