Parents are running out of fingers to count the principals at Southwest Detroit Community School.

Four different principals have left since the charter school’s founding in 2013. Only one lasted more than a year, and he left his job last month, sending school operators on yet another search for an administrator who can help the school recover from its turbulent start.

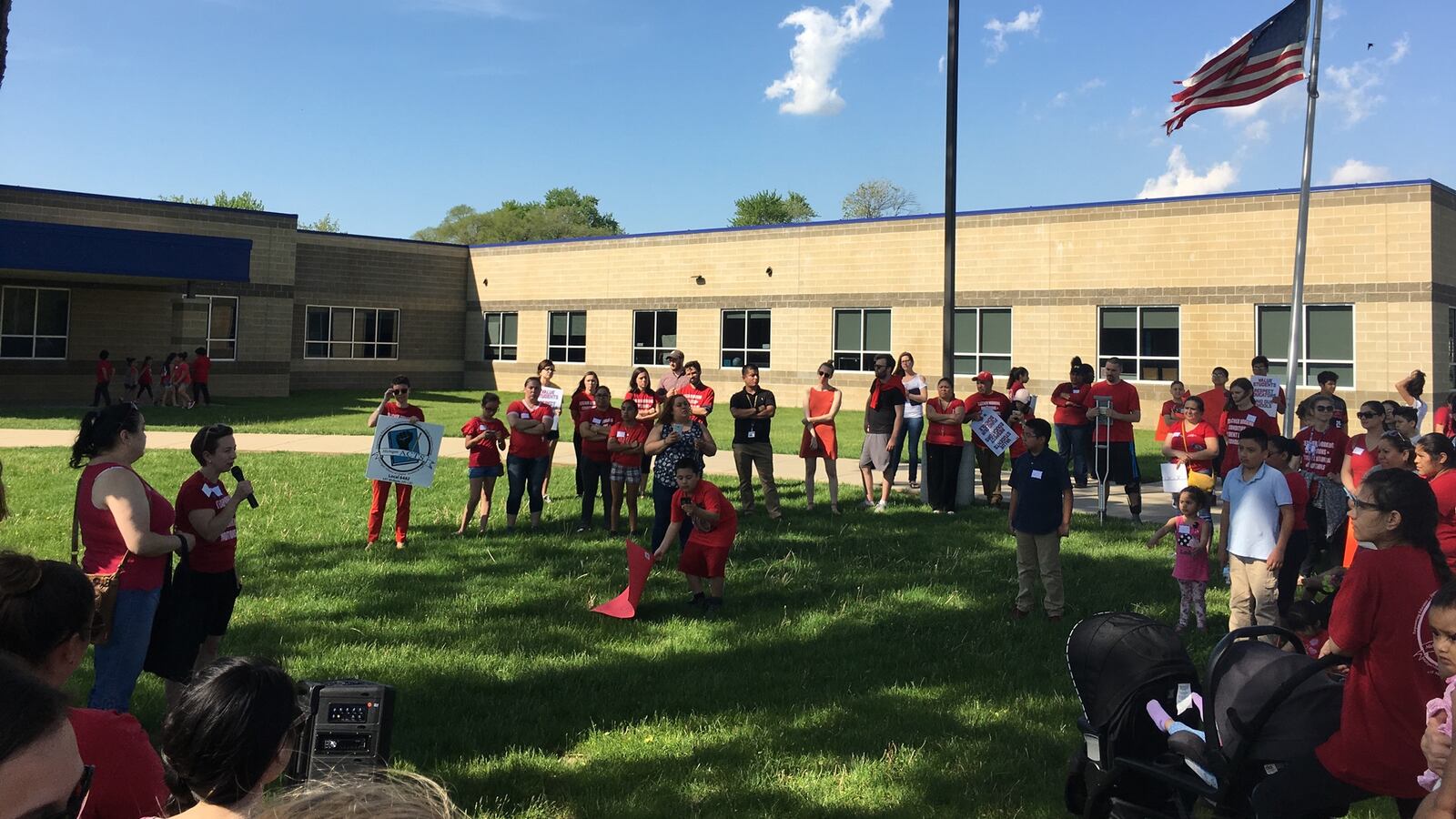

Parents crowded into the gym last month to protest the revolving cast of administrators, who they say have failed to do the long-haul work of providing a quality education. The school’s path from a promising beginning to a looming closure shows the profound challenges facing even the best-supported efforts to build a successful school in Detroit. Any group hoping to educate its students must face a landscape where there are more school seats than children, competition for schools is fierce, and funding is based almost entirely on enrollment.

“If the school is going to move up, we need consistency,” Jennie Weakley, a parent at the school, said after the meeting.

Her daughter thrived at the school at first, joining the orchestra and connecting with her third-grade teacher. Then the familiar faces began to disappear, and it wasn’t just the principals. The third-grade teacher left, too, Weakley says. Her daughter went on to have six more teachers in the next two years.

When Florida-based Lighthouse Academies announced plans to open a school in Detroit, it broke ranks with other national charter companies, which have largely stayed away from the city.

Charter operators play the role of a school district — they hire teachers, choose curriculum, and keep track of student data — and some observers hoped that a national operator like Lighthouse would use administrative tools honed in other cities to bring some stability to Detroit students.

Parents were involved with Lighthouse from the start. Before the school opened, Lighthouse sent an employee to Michigan who built a neighborhood coalition to support starting a new school on the site of Newberry Elementary, a district school that closed in 2005 and was later demolished.

“We had youth, we had community stakeholders, we had parents, we had teachers who had a say-so in what the school structure would look like,” said Elizabeth Santos, a resident who joined the neighborhood coalition, then shaped the school’s policies as one of the first presidents of its school board.

To raise funds for a new school building, the group settled on Turner-Agassi, an investment fund affiliated with tennis star Andre Agassi, which agreed to build a school on the site and lease it to Lighthouse at a rate that would start out low and increase once the school had a chance to attract students, said Heather Gardner, president of EAS Schools, which currently manages the school.

But the school’s hopeful beginning began to wear thin. Teachers and administrators kept leaving, and Lighthouse operated the school at a loss, neglecting to build the reserves that would be needed to continue paying the lease. Several parents described their dismay when they said they were told that the Lighthouse representative who helped found the school was dispatched to expand the company’s presence elsewhere in southeast Michigan.

After three years, Lighthouse pulled out, and parents found themselves in a community meeting debating how best to replace the organization that had brought them together.

It was a low point for the parents, but some charter observers were not surprised.

“It’s the same story in different locations,” said Tashaune Harden, vice president of the Michigan Alliance of Charter Teachers and Staff, the union representing teachers at the school.

With Lighthouse gone, Detroit’s charter landscape looks much the same as before. Most schools — including the renamed Southwest Detroit Community School — are run by local companies that lack the advantages of operating on a broader scale.

“Like much of Detroit’s comeback, our charter community is mostly homegrown,” said Rob Kimball, associate vice president for charter schools at Grand Valley State University, which authorizes dozens of schools in Michigan, including Southwest Detroit Community School.

No matter who replaced Lighthouse, they would face steep odds. The school’s academic performance was poor — it was placed under state oversight in March after ranking in the bottom five percent of schools statewide — and it was becoming increasingly difficult to keep up with payments on the building. What’s more, the school’s charter would expire in 2020, and school leaders worried that they would need to show improvement to win a new contract from Grand Valley, one of the state’s largest authorizers.

The board’s eventual choice, EAS Schools, promised a singular focus on the school when it took over almost two years ago. Gardner, its president, previously worked for Michigan’s charter school association, where she helped bring Lighthouse to Detroit. When it pulled out, she turned her education consulting organization into a charter operator with the goal of turning the school around.

Lighthouse’s departure was “really devastating,” Gardner told Chalkbeat. “A lot of research was done, a lot of site visits, a lot of time went into that. It was thought that we were bringing something really important and really amazing to the area, and it didn’t turn out that way.”

Gardner won parents and the school board over with a promise of continuity. Parents would continue to play a key role in decision making, and Gardner’s company would make Frank Donner the new principal.

Donner was popular among parents, and some say they supported Gardner’s company in part because she promised to keep him in place.

But as he neared the two-year mark and test scores failed to rise quickly enough, Gardner says she began to doubt whether Donner, who had never worked as a principal before, was experienced enough to pull off a school turnaround.

The school already had its share of problems. Now, faced with closure by the state if its ranking failed to improve within three years, it was running out of time.

Earlier this month, Gardner offered Donner a job as an assistant principal at the school, but she says he chose to leave instead. Donner did not respond to requests for comment.

“He knew all the families,” said Mariana Hernandez, who has two children at the school. “When we lost him, we were really upset. It was like we lost a member of the family.”

Last week, change-weary parents filed into the gym once again with their own solution for improving the school. This time, they wanted the board to approve a contract for the school’s fledgling teachers union, which they hoped would reduce teacher turnover.

But for many at the meeting, the school’s problems go far beyond teacher pay.

Some parents mentioned Donner by name, blaming EAS for his dismissal. Several were outraged that the school spent only five percent of its $5,000 budget for sports this year. Many spoke about teacher turnover and a lack of classroom aides.

“What we all want is consistency and relationships,” said parent Jillian Howard. “If the turnover continues, how can our students excel?”

Parents nodded in agreement, many sitting on folding chairs brought out to handle the overflow crowd. The strong attendance was a sign that instability at the school hasn’t undercut its hallmark parent participation, at least for now.

Maria Orozco enrolled her fifth-grader at Lighthouse in the school’s first year. She knew Donner, and feels cut off from the new school managers, who have asked her to email her concerns even though she doesn’t have an email address.

“If it doesn’t stabilize,” she said, speaking in Spanish, “I’m going to have to take my kids somewhere else.”