A Detroit charter school network is sharply downsizing after losing its contract with the city’s main district, a long-anticipated development that still seemed to take the network’s leaders by surprise.

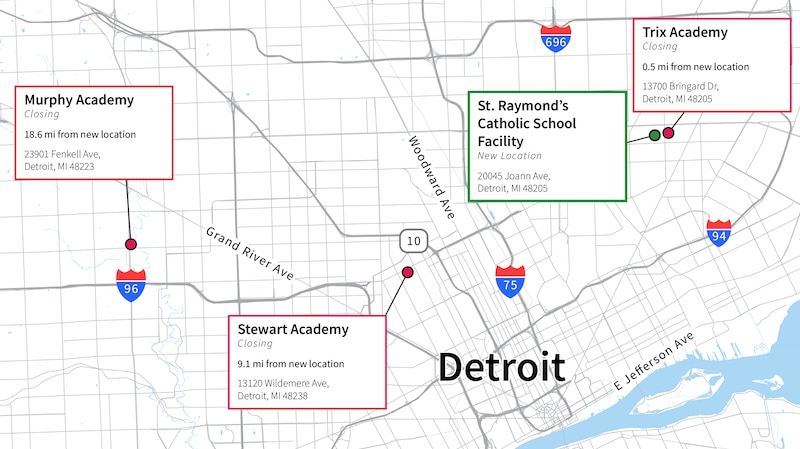

More than 700 students at Trix, Stewart, and Murphy academies will be affected by the resulting scramble to consolidate the schools into a new building on Detroit’s east side.

“I’m left in shambles,” said Shevoyn Giles, a hospice worker whose son attended Stewart. “The new school is 11 miles from my home, so I have to find transportation for him to get there.”

The closures have loomed since November, when Superintendent Nikolai Vitti told the Detroit school board that the city’s main district should get out of the charter school business. He argued that the district was wasting resources by providing oversight to Stewart, Trix, and Murphy, along with a handful of other schools.

Even as some jumped ship, leaders of those three schools held out, hoping their contract would be renewed. When it wasn’t, they had to act quickly. But they couldn’t prevent the closure of the schools, or a sharp reduction in their student enrollment and staff.

The new building will also be called Trix Academy, but it will effectively be a new K-8 school, staffed by teachers from the three schools who survived a 50 percent staffing cut. Some students will choose to stay — Giles, for one, doubts she can find better special education services anywhere else.

But many more are expected to join the large number of Detroit students who move to new schools every year. In part because the new building is so far from two of the shuttered academies, the charter network anticipates that enrollment will fall to 350 this year, less than half of the current enrollment and far below the capacity of the new school building.

It is the latest episode in the turbulent aftermath of the state’s attempt to turn around Detroit Public Schools. Stewart, Trix, and Murphy were among the lowest performing schools in the district when a state-appointed emergency manager converted them to charter schools and placed them under the oversight of the Education Achievement Authority, a state-run recovery district tasked with turning around 15 struggling schools in the city.

Last year, the recovery district dissolved, and the three charter schools were forced to find a new sponsor. Although new school board members argued that students at the three schools belonged in the district, they ultimately settled on a short-term compromise: The district would provide oversight to the schools and allow them to remain in district buildings, but the board would re-evaluate the decision in a year.

James Schelberg, chair of the board that oversees the three schools, said he spent most of that year expecting the district to continue the arrangement for at least three more years.

“I certainly expected” that the charter would be renewed, Schelberg told Chalkbeat.

Some within the district were sympathetic: When the one-year charter was renewed, the director of the district’s charter school office argued for a five-year charter.

But Vitti had expressed doubts about the arrangement almost as soon as he arrived in Detroit last year, saying that overseeing charter schools would take resources away from the district’s other priorities. The board eventually agreed after putting off a decision in November.

“Through a discussion of the contract during committee meetings, Dr. Vitti and the Finance and Academic Committees decided not to renew the contract,” said Chrystal Wilson, a district spokeswoman.

Phalen Leadership Academies, the company that managed the three schools over the last year, began discussing its options with Central Michigan University’s Center for Charter Schools in the spring. It started the formal process of applying for a new charter on May 21, the same day the news broke that the school board had decided not to renew the charter, Janelle Brzezinski, a spokeswoman for the university charter office, said.The board’s decision left Phalen with more problems than could be solved in a summer. The three school buildings were owned by the district, so the company had to hunt for new space in addition to a new charter.

A charter was approved on July 1. Brzezinski, the Central Michigan spokeswoman, said that test scores at the three schools showed “promising academic growth” in Phalen’s first year managing them. She noted that the new Trix building is located in a Detroit neighborhood with more students than seats in school.

Schelberg says the network didn’t want to downsize, but it only requested a charter for one school, having realized that they wouldn’t be able to find three buildings that could pass the myriad safety inspections required for schools.

“It kills me that we had to lose both the students and the staff,” he said.

Those changes came quickly. Two teachers who worked at the school last year said they learned about the staffing cuts on the last day of school. (They asked not to be named to protect their future employment prospects.)

The teachers worried that some parents still don’t know about the changes. Giles learned of the closures in July, but did every parent receive that phone call?

“I don’t think so,” she said.

Earl Phalen, president of the company that ran the three schools, declined to comment.

Michelle McConnico, a spokeswoman for Phalen, said the company has done as much as it can to tell parents about the change. A timeline she provided says the company began looking for a new location in late May, and held informational meetings about the transition for parents about a month later, on June 18 and 19. About a month after that, on July 23, school staff called parents directly to find out if their children would be returning to the school.

That’s when Giles learned that she would have to make special arrangements for her 10-year-old son, who has autism.

At Stewart, he was placed in a classroom with his non-disabled peers. She worries that he’d be placed in a separate track if he changes schools.

With the first day of school less than two weeks away, Giles plans to send her son to the new Trix Academy on the other side of the city, joining the ranks of Detroit parents who make extraordinary efforts to get their kids to school. In the mornings, when she works at the hospice, she’ll rely on her parents. In the afternoons it’ll be up to her to cross the city to pick up her son.

She just hopes he’ll be able to adjust.

“Change is difficult for him,” she said.

Update: August 23, 2018: Story has been updated to include a comment from Chrystal Wilson, a spokeswoman for Detroit’s main district.