Para leer este artículo en español, oprima aquí.

If you think it’s hard to navigate Detroit’s troubled school system, try doing it when no one speaks your language.

The latest stop on Chalkbeat Detroit’s listening tour took a parent’s-eye-view of the obstacles facing English language learners, who graduate from high school at lower rates than their English-speaking peers.

One observation: The parents, who play a key role in helping children learn to read, face plenty of obstacles themselves, especially when it comes to communicating across a language barrier.

“You feel that you don’t have value,” said Gloria Vera, describing her interactions with English-speaking school staff. “You feel that you have fewer chances to ask questions. It scares me.”

Several mothers worried about the effects of Michigan’s “read-or-flunk” law, which will hold back third-graders if they aren’t reading on grade level by the end of next year. By one count, 70 percent of English learners in the state could be forced to repeat a grade.

One mom said she wanted to help her daughter learn to read, but worried her English skills were too limited.

Another, Delia Barba, suspects that her daughter has a learning disability, but says her school in mostly Spanish-speaking Southwest Detroit has been slow to investigate because of the language barrier.

Like virtually every parent present, Barba said a few more bilingual staffers would go a long way.

“We don’t know who to talk to,” Barba said, speaking in Spanish. “They don’t speak Spanish.”

At each stop on Chalkbeat Detroit’s listening tour, parents take center stage to tell us the stories we should be covering. (See the results of our last stop here.) This time around, Chalkbeat joined with organizations that work with Detroit parents to hear from dozens of mostly Spanish-speaking mothers. They traveled through a Tuesday morning rainstorm to the headquarters of Brilliant Detroit, a nonprofit that provides social services like literacy training to families around Detroit.

Some of the parents on hand had already worked with neighborhood organizations like Congress of Communities and the Detroit Hispanic Development Corporation to push leaders of Detroit’s main district to provide more access to Spanish-speaking parents, noting their concerns have been brushed off by previous administrations.

“Community residents feel frustrated in 2018, because they have expressed the need for language access repeatedly over the years and a resolution is continually brushed aside,” said Elizabeth Rojas, a community advocate and parent in the district.

At a meeting last month, Superintendent Nikolai Vitti agreed to establish a Spanish hotline and ensure that every school with Spanish-speaking children has someone in the office who speaks Spanish, among other promises.

After surveying families in the neighborhood, parents are turning their attention to the issue of safety in schools. They’re hoping that schools will hire more bilingual security guards, and that undocumented parents will be allowed to enter school buildings with an alternative form of ID, such as a Mexican passport, a state ID, or even an ID issued by the district itself.

Parents on hand Tuesday reported similar access issues at charter schools in Southwest Detroit. Angelina Romero, who arrived with her family from Mexico within the last two years, worried that her first-grade son wasn’t picking up English at a neighborhood charter school, and that she had trouble communicating with his teacher.

“I’m hoping that the families who came here realize that it’s not just parents at their school that are concerned and active on this issue,” said Jametta Lilly, CEO of the Detroit Parent Network, which co-sponsored the listening session with Chalkbeat.

For Gloria Vera, the language barrier added to the challenge of navigating a broken special education system. After her daughter was diagnosed with autism, officials at a local school told her they didn’t have enough space.

“They told me, no you can’t enroll your child here,” Vera said, speaking in Spanish.

Staff at the school gave her a phone number to call — presumably to the district’s enrollment center — but Vera worried that it wouldn’t do her any good.

“I didn’t know English,” she said. “I felt lost.”

Looming over the conversation was Michigan’s third-grade reading law, which lends a sense of urgency to the already daunting challenge of helping a child read in a second language.

Yesenia Hernandez said she reads to her second-grade daughter in English, but worries that she can’t pronounce words correctly. In these moments, she said in Spanish, it seems that “she’s learning, but I’m just confusing her.”

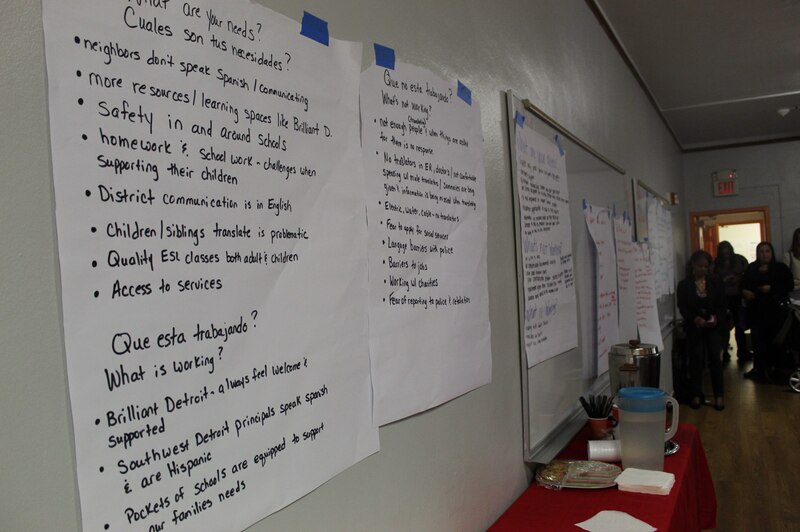

Working with a group of five other mothers, Hernandez listed out the ways her school could help her to help her daughter. In another room, other small groups worked on wish lists of their own, and when they compared results, there were striking similarities: The parents wanted to communicate with their children’s schools in Spanish, and they wanted the tools — like classes in English for adults — to help their children learn. One group gave an approving nod to the “parent room” at Priest Elementary-Middle School, where Spanish-speaking parents gather and share information and resources.

Even as they hurry to help their children build reading skills, parents are uncertain about how their children might react to flunking a grade when the state’s high stakes reading requirements go into effect next school year.

Delia Barba thought the policy made sense: “What if they keep saying pass, pass, pass, and he doesn’t know how to read?” she asked.

But Gloria Vera wasn’t so sure. In her neighborhood, an estimated 8 in 10 students spoke some Spanish at home. How many would be held back?

“In this part of Detroit, there should be a solution,” she said.